The Pegasus Project is an international investigative journalism initiative that revealed governments’ espionage on journalists, opposition politicians, activists, business people and others using the private Pegasus spyware developed by the Israeli technology and cyber-arms company NSO Group.

The investigation by The Guardian and 16 other media organisations suggests widespread and continuing abuse of NSO’s hacking spyware. The leak contains a list of more than 50,000 phone numbers that, it is believed, have been identified as those of people of interest by clients of NSO since 2016. Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based nonprofit media organisation, and Amnesty International initially had access to the leaked list and shared access with media partners as part of the Pegasus project, a reporting consortium. According to Priest (2021), “a UAE agency put Pegasus spyware on phone of Jamal Khashoggi’s wife months before his murder.” This, sh suggests — based on new forensics evidence — challenges NSO claims that the murdered journalist’s wife, Hanan Elatr, ‘was not a target.’” Kirchgaessner (2021) writes that there “definitely people who refer to the Pegasus spyware tool from NSO Group as a weapon.” For further information on this matter see: Amnesty International (2021), Cohn (2021), Forbidden Stories (2021), Stelter (2021), The Guardian (2021), The Washington Post (2022).

Pegasus as a case study of evolving ties between the UAE and Israel

— Kristian Coates Ulrichsen (2022, June 9), Gulf State Analytics

Concerns over the deployment of Pegasus, a sophisticated form of spyware developed by the NSO Group, an Israel-based and Israeli-owned technology company, burst into the mainstream media and political discourse in 2021 with the publication of the Pegasus Project, an investigative initiative involving a global consortium of journalists, in July, and the subsequent release, in October, of a high court ruling in the United Kingdom that the Ruler of Dubai had used Pegasus to hack the mobile phone of his ex-wife. In both cases – the Pegasus Papers and the High Court judgement – the UAE figured prominently as one of the most active users of the controversial spyware. Analysing the trajectory of Pegasus in the UAE offers a case-study in how relations with Israel evolved over the past decade and reached the point where close security coordination was supplemented, in August 2020 and the Abraham Accord the following month, by the normalization of political relationships between the two countries.

This analysis explores the trajectory of Pegasus and the NSO Group in the UAE against the backdrop of the evolving security and defense (and, later, political) relationship between the UAE and Israel in the tumultuous decade that began with the Arab upheaval in 2010-11 and ended with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in early 2020. This was a period that encapsulated broader events that provided contextual bookends to the story of Pegasus in the UAE – an assassination carried out by Mossad operatives in Dubai in January 2010 that inflicted significant damage on tacit UAE-Israel relations for several years, and the mounting difficulties facing both the NSO Group and Benjamin Netanyahu’s premiership that culminated in the former’s ousting in May 2021 and the latter’s blacklisting in the U.S. in November 2021.

There are three parts to this analysis, which begins with a brief historical overview that sketches the pre-2010 landscape within which UAE-Israel relations later evolved (and shows how far and how fast they developed compared to what had gone before). The main bulk of the analysis is the second section which is the case study of Pegasus in the UAE against the inescapable backdrop of the thickening web of security and defense networks that drew the UAE and Israel closer together in the aftermath of the Arab Spring and laid the groundwork for the political breakthrough with the normalization agreement of August 13, 2020. The final section consists of three concluding observations about the case study and ends with a consideration of what may happen next given the difficulties that NSO Group has become embroiled in.

Oil’s ‘blessings’ & the American dollar standard

📕 “Political maps of Arabia” →

Historical context

Relations between the UAE and Israel were virtually non-existent during the first three decades after the creation of the federation of the United Arab Emirates on December 2, 1971. Although not a front-line state in the Arab-Israeli wars, the UAE during the long leadership of its founding president, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan (Ruler of Abu Dhabi since 1966 and President of the UAE from 1971 until his death in November 2004) maintained a commitment to ‘Arabness’ and especially to Palestine. This was a constant and guiding feature of Emirati foreign policy during Sheikh Zayed’s life and was manifest in political and financial support to the Palestinian cause. The UAE participated in the Arab oil embargo between October 1973 and April 1974 and provided medical supplies to the front-line states during and after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, consistent with a declaration by Sheikh Zayed in 1971 that “No Arab country is safe from the perils of the battle with Zionism unless it plays its role and bears its responsibilities, in confronting the Israeli enemy.”

As late as 2001, Sheikh Zayed dismissed the September 11 terrorist attacks, in which two of the 19 hijackers had been Emirati nationals and much of the logistical and financial support for the attackers had passed through the UAE, as either perpetrated by the CIA or by Mossad. What changed the equation and fundamentally re-set the parameters of what was possible in UAE-Israel ties was the rise to decision-making prominence of Sheikh Zayed’s third son, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (MbZ), who was brought into the line of succession in 2003. Following Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan’s passing in May 2022, MbZ became the UAE’s third president and ruler of Abu Dhabi, making him the official ruler of the UAE. Yet due to a series of strokes between 2009 and 2014, Khalifa bin Zayed withdrawew from public life with political authority concentrating in the court of MbZ many years before he officially became President of the UAE.

MbZ acted decisively to respond to a changing threat perception especially after the shock of the Emirati involvement in the September 11 attacks in the United States. A decade later, the Arab uprisings provided a further impetus to deepen the ‘security state’ that increasingly took a ‘zero-sum’ approach toward acts that could potentially lead to instability or violent extremism. MbZ was especially focused on the perceived threat from Islamist groups after he held a series of meetings with Emirati Islamist leaders in the 2000s that failed to reach agreement on their disengagement from political activities. It was against this backdrop of a security-first approach to domestic politics and regional affairs that NSO Group and Pegasus entered the Emirati landscape in the 2010s.

NSO Group was formed in Israel in 2010 and staffed primarily by veterans of Israel’s intelligence agencies, especially the Israeli Military Intelligence Directorate, AMAN. That same year, (undeclared) relations between the UAE and Israeli reached a low-point in the post-2004 (post Sheikh Zayed) era in January 2010 when 27 operatives subsequently linked to Mossad entered the UAE and carried out the audacious killing of Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, a chief weapons negotiator for Hamas. The death squad killed al-Mabhouh in his hotel room in the Al Bustan Rotana hotel in Dubai and entered and exited the UAE without informing the Emirati authorities of their presence in the country still less of their reasons for being there. The fact that Israel carried out this operation on Emirati soil without informing their UAE counterparts reportedly enraged Emirati officials and cooled the undeclared UAE-Israel relationship for several years.

The fallout from the al-Mabhouh killing paused but did not stop altogether the discrete and largely under-the-radar connections between Emirati and Israeli individuals and entities, especially in the security and defense sectors. The start of the ‘Arab Spring’ revolts a year later changed the regional context within which both the UAE and Israel operated and provided a point of convergence of Emirati and Israeli interests around a common set of strategic and geopolitical fault-lines. These included shared concerns about the potential (and, in some post-2011 political transitions, actual) empowerment of political Islamist groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood, the broader challenge to security and stability that was perceived to emanate from the breakdown of political authority in multiple Arab states after 2011, and a view that Iran and its regional behavior needed to be contained more forcefully – especially after neither Tel Aviv nor Abu Dhabi were included in the P5+1 negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program.

Pegasus in the Emirates

In January 2022, a year-long investigation into NSO Group and Pegasus by the New York Times revealed that Israeli officials offered Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince the opportunity to acquire Pegasus as a ‘truce’ offering that would restore the discrete UAE-Israel security and defense relationship and repair the ties damaged in 2010. This disclosure is consistent with reports that NSO and its products, especially Pegasus, played a key role in Israel’s diplomacy and outreach to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member-states during the long premiership of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who was in office throughout the period of NSO’s emergence in 2010 until June 2021, four months before the NSO Group was blacklisted by the U.S. Department of Commerce for its “malicious cyber activities.”

For MbZ, the Pegasus offer came at an opportune moment as the UAE pursued domestic political opponents, holding a mass trial that was widely criticized by international human rights organizations and sentencing 69 defendants to lengthy prison sentences on spurious charges of plotting an Islamist coup in July 2013. Also at that time, Abu Dhabi developed a far more assertive and interventionist regional policy that sought not only to contain but also to roll back Islamist gains across the post-Arab Spring political landscape, beginning with the immediate political and financial support to the military-led government that toppled the Muslim Brotherhood presidency of Mohammed Morsi just one day after the end of the mass trial of political activists in Abu Dhabi.

It should be noted that Pegasus (and NSO) were not the only Israeli products that came to underpin the revival and strengthening of Israel-UAE relations after 2013. Some of the other connections initially developed in the late-2000s, before the Dubai debacle, but only grew into significant operational partnerships after 2013. A case in point was AGT International, a Geneva-based company owned by an Israeli businessperson, which in 2015 was linked in media reporting with a joint venture (through a Swiss intermediary) with two Emirati firms, Advanced Integrated Systems and Advanced Technical solutions, for a comprehensive emirate-wide surveillance initiative in Abu Dhabi named Falcon Eye. A report on Falcon Eye by Middle East Eye, a UK-based website with alleged links to Qatar, described the civil surveillance network as one that ensured that “every person is monitored from the moment they leave their doorstep to the moment they return to it.”

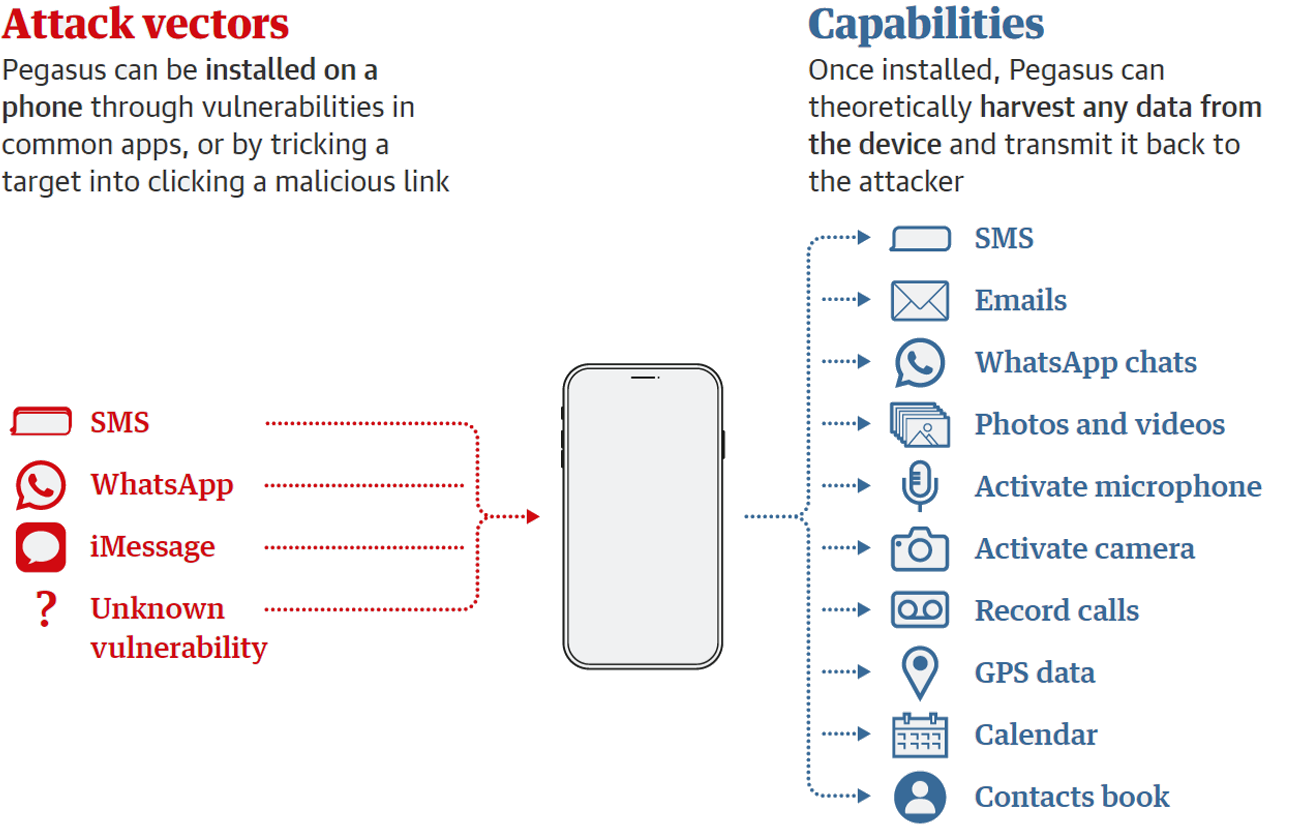

The domestic and regional security environment within which Pegasus was made available by Israel to the UAE means it is little surprise that, in 2016, credible evidence of spyware linked to the NSO Group was discovered on a mobile telephone that belonged to Ahmed Mansoor, an internationally-recognized human rights defender who had been one of the few UAE-based advocates prepared to raise in public their concerns at the erosion of human rights and civil liberties in the UAE in and after 2011. In August 2016, Citizen Lab, a laboratory based at the University of Toronto that has, since 2001, tracked internet security and threats to human rights, revealed that Mansoor had been targeted by “zero-click exploits” that had sought to penetrate his iPhone, in part through text messages that promised to reveal “new secrets” about detainees held in UAE prisons if he opened an included link. This was a targeted attack that included a link that was highly specific to Mansoor and his work in an attempt to penetrate and gain access to his phone.

In March 2017, Mansoor was detained by twelve members of UAE state security at his home while his electronics were seized; after being held largely in solitary confinement and with little access to family visits or access to legal representation, he was convicted in the State Security Chamber of the Federal Appeals Court and sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment in May 2018 for insulting Emirati leaders by using social media “to publish false information and rumors’ that ‘harm national unity and social harmony and damage the country’s reputation.”

The case of Ahmed Mansoor is not the only incident where the UAE has been linked with the deployment of Pegasus against perceived opponents and critics of the government, whether at the federal level in Abu Dhabi or at the local emirate-level government, especially in Dubai. The UAE was alleged to be one of the most extensive users of Pegasus when the files of the Pegasus Project were made available in the summer of 2021 with more than 10,000 people of interest to the UAE uncovered in the files (although not necessarily the target of a subsequent penetration, successful or otherwise). The list of people of interest included Matthew Hedges, a British PhD student who was detained on a research trip to the UAE in May 2018, later sentenced to life imprisonment for “spying” (despite no evidence being presented to support the allegation), and subsequently released and returned to the United Kingdom following a public and political outcry in November 2018. Another name that appeared on the list of people of interest was Alaa al-Sadiq, a former president of the Emirates National Student Union and a human rights advocate and executive director of ALQST, a London-based Saudi-focused human rights organization, who lived in exile in the United Kingdom (after her father was one of the 69 convicted in the mass trial in 2013) until her sudden death in a car accident in England in June 2021.

Further details about the utilization of Pegasus by UAE users emerged in a ruling by the Family Division of the High Court in London (for England and Wales) in 2021 on the divorce settlement between Princess Haya bint Al Hussein of Jordan and her estranged husband, the Dubai ruler, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum. Princess Haya left the UAE in May 2019 in fear of her life and sought refuge in the U.K. with her (then) twelve-year-old daughter and seven-year-old son, the youngest of Mohammed bin Rashid’s children. In an explosive judgement made public in October 2021, Andrew McFarlane, the most senior family court judge in the U.K., ruled that “agents of Dubai and the UAE” hacked the telephones of Princess Haya and five of her associates in July and August 2020, including two of her lawyers, one of whom, Baroness Shackleton, is a serving parliamentarian in the House of Lords, her personal assistant, and two members of her security staff.

In his judgement, McFarlane stated that “the findings represent a total abuse of trust, and indeed an abuse of power”. Reporting on the case, in which the NSO Group cooperated with the court’s inquiries, CNN noted the full range of capabilities that a successful penetration of an iPhone by Pegasus could unlock, including “the capacity to track the target’s locations, listen to their telephone calls, access their contacts lists, passwords, calendars, and photographs, and read messages received through apps, emails, and SMS.” (Lady Shackleton and her colleague, Nicholas Manners, were not the only instance of lawyers being targeted by Pegasus, as Rodney Dixon, QC, a human rights lawyer who represented clients of interest both to the UAE – Matthew Hedges – and to Saudi Arabia – Hatice Cengiz, the widow of the slain columnist Jamal Khashoggi – was also found to have been the target of an unsuccessful Pegasus infiltration in 2019).

The revelations about the misuse of Pegasus in the case of Princess Haya carried significant weight because, rather than being the outcome of media reporting which may or may not be credible, substantiated, or exaggerated, they were entered into a judgement, and formed in part the basis for a ruling, at the High Court, and thus were shown to have been treated on the balance of probabilities as credible and substantiated by a court of law. For this reason, the judgement in the Princess Haya case caused significant additional damage to the reputation of NSO Group and may have contributed to the placing of NSO on a trade blacklist maintained by the Bureau of Industry and Security at the U.S. Department of Commerce on November 3, 2021. A statement released by the Department of Commerce declared that NSO Group, as well as three other companies, were added to the Entity List as part of “the Biden-Harris administration’s efforts to put human rights at the center of U.S. foreign policy, including by working to stem the proliferation of digital tools used for repression.”

In addition to the difficulties faced by NSO Group, whose capacity to license and operate its products, including Pegasus, was severely restricted by the Commerce Department listing, the UAE also faced consequences and reputational damage, which included having its license to operate Pegasus withdrawn. Moreover, additional reporting by Haaretz in November 2021 disclosed that the UAE had in fact possessed not one but two licenses for Pegasus and that despite the federal government (based in Abu Dhabi) having responsibility for foreign, security, and defense affairs, the emirate of Dubai had acquired its own, separate, Pegasus spyware package from NSO Group. As Aytan Avriel, the Haaretz journalist who broke the story, asked, ‘Why does UAE – one country with a joint federal military, police, and security force, need two separate NSO spyware systems held by two different leaders?’ in reference to MbZ in Abu Dhabi and Mohammed bin Rashid in Dubai.

Allocating oil-rent (“resource wealth” matters)

📕 “The Arabian Gulf Social Contract” →

📕 “Arabian Gulf sovereign wealth” →

Open questions

A question therefore arises as to why the leadership in Dubai wished to acquire its own license to operate Pegasus and whether it has any wider implications for the coherence (or lack) of UAE-wide security and policing structures, any residual desire by Dubai to retain tools and capabilities separate from Abu Dhabi, as well as the question of whether those separate capabilities could potentially have encompassed use against targets defined as a specifically Dubai person of interest, including elsewhere within the UAE.

The broader question posed by the apparent (mis)use of Pegasus by UAE operators against lawyers, academics, human rights advocates, and individuals such as Princess Haya engaged in personal disputes against people of influence, concerns the operational safeguards that ought to have restricted the utilisation of Pegasus against targets deemed to be legitimate threats to security. It is this elasticity in usage which has got the NSO Group into difficulty in the U.S. and done such damage to the company’s reputation. While the company has acted retrospectively to cancel the licenses of operators such as the UAE, this appears to have happened only ‘after the fact’ and once damaging revelations have occurred, and any transgressions do not seem to have been prevented by any operational safeguard in practice.

Part of the problem may lie in the expansive definition of ‘terrorism’ in the UAE’s Federal Law No.7 of 2014, which international human rights groups have criticized for containing clauses so broad that almost any act could be classified as “terrorism.” Included in the definition in Article 1 of the law of a “terrorist outcome” was “stirring panic among a group of people” and “antagonizing the state” without including any definitional qualifiers, while Article 14 set the death penalty or life imprisonment for anyone who acts with intent “to undermine the stability, safety, unity, sovereignty, or security of the State” or “to undermine national unity or social peace.” Article 15 stipulated sentences of between three and 15 years for anyone who “publicly declares his animosity or lack of allegiance to the State or the regime.” As Human Rights Watch observed in a deeply critical report on the new law, these sweeping powers soon led to the first conviction of a man for “damaging the reputation of UAE institutions,” among other things.

It might therefore be surmised that the operators of the Pegasus licenses in the UAE were merely following Emirati guidelines in pursuing “terrorists” or other legitimate security threats when they selected targets with no violent intent and engaged in activities that would not be regarded as threats to security in many jurisdictional settings outside of the UAE. It is this difference in definitions which could explain why the UAE selected the targets that it did and why its Pegasus operators might credibly have believed they were utilizing the product within its permissible parameters, however much of a stretch that may appear to observers based outside the UAE itself. However, when such practices were disclosed, either in court (in the case of Princess Haya) or through investigative journalism (such as the Pegasus Project), the international backlash was such that it had a negative impact on the international image of the UAE.

Several broader conclusions arise from this examination of Pegasus as a case-study in the evolving relationship between the UAE and Israel. The first is that bilateral ties continue to be based in the security and defense space, which is where the shared commonality of UAE-Israel interests is strongest and most durable. As Emirati leaders have built a surveillance system that is one of the most encompassing (and intrusive) in the region and as they have increasingly adopted a ‘zero-tolerance’ approach to instability that aims to pre-emptively identify and counter threats to security before they are given the time and space to escalate, it is perhaps unsurprising that they should look to Israel for material (and ideational) support, given Israel’s long experience in surveilling and controlling its Palestinian communities both within Israel and inside the occupied territories.

A second, related, observation is that, despite the normalization of political relations in August 2020 and the signing of the Abraham Accords between Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain at a White House ceremony on September 15, 2020, ties between the two countries remain largely concentrated among policymakers and businesspeople rather than the wider population, especially on the UAE side. (While tens of thousands of Israelis have traveled to the UAE to visit Dubai and Abu Dhabi, providing a boost to tourism at a time when the sector continued to be hit by the Covid-19 pandemic, there were far fewer Emirati visitors to Israel). The nature of security, defense, and intelligence work is that it involves a select group of operatives, and this was evident in the discrete acquisition and deployment of Pegasus where decisions were taken and implemented by senior policymakers clustered around those in authority. By its very nature, Pegasus was not a product that could be marketed to, or used by, a wider group, and this was a reflection also of the broader nature of the densest web of Emirati-Israeli connections in practice.

The third observation relevant to this case-study is that media reporting of the use of Pegasus and NSO Group by the Netanyahu government for diplomatic purposes, and specifically to support and advance Israel’s diplomatic outreach to GCC states, appears to be borne out in the UAE case. It was Pegasus that the Israeli leadership reportedly offered to MbZ in 2013 to overcome the impasse in security and defense relations after the Mossad killing of al-Mahbouh in 2010 and it was the reactivation of the Saudi access to Pegasus that Israeli officials are said to have offered Mohammed bin Salman in return for the opening of Saudi airspace to Israeli air traffic in late-2020. This latter issue may not have been a matter directly related to the UAE, but the opening of Saudi airspace was critical to the viability of UAE-Israel flights, and greater Saudi buy-in (if not outright acceptance of) the Abraham Accords was important to the UAE leadership for the signal it gave of approval of the Emirati action.

Pegasus may have played an important role in (and after) 2013 in repairing UAE-Israel ties and solidifying a bilateral relationship that was able to broaden beyond its defense and security base to encompass the establishment of full political and diplomatic relations in 2020, but the ‘post-normalization’ context is such that the Israel-UAE relationship will survive the NSO Group and the backlash over Pegasus, as it has acquired a depth and a breadth that simply did not exist in the early 2010s. For these reasons, Pegasus was one of the factors that brought Israel and the UAE closer together at a critical moment in time during the post-Arab Spring decade of confrontational regional geopolitics for both countries.

| i | This is the website of Dr Emilie J. Rutledge who, with almost two decades’ worth of experience in managing, designing and delivering university-level economics courses, is currently Head of the Economics Department at The Open University.

erutledge.com  Dr Emilie J. Rutledge Emilie has published over 20 peer-reviewed papers and is the author of “Monetary Union in the Gulf.” Her current research focus is on employability, the feasibility of universal basic incomes and, the oil-rich Arabian Gulf’s economic diversification and labour market reform strategies. On an ad hoc basis, Emilie provides consultancy on developing interactive university courses, alongside analytical insight on the political-economy of the Arabian Gulf. |