UN Resolution 194 (December 11th, 1948) states that:

Palestinian refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.

📕 “Palestine: The One State Solution” →

Pamphlets on Palestine

|

‘You Feel Like You Are Subhuman’: Israel’s Genocide Against Palestinians in Gaza (2024, December 5) MDE 15/8668/2024 Amnesty International, London. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde15/8668/2024/en/ 🖨 Print-friendly PDF |

|

Extermination and Acts of Genocide (2024, December 19) Human Rights Watch, New York. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/12/19/israels-crime-extermination-acts-genocide-gaza 🖨 Print-friendly PDF |

|

Gaza: Life in a death trap (2024, December 19) Médecins Sans Frontières, Geneva. https://www.msf.org/msf-report-exposes-israel’s-campaign-total-destruction 🖨 Print-friendly PDF |

Books, Extracts, etc.

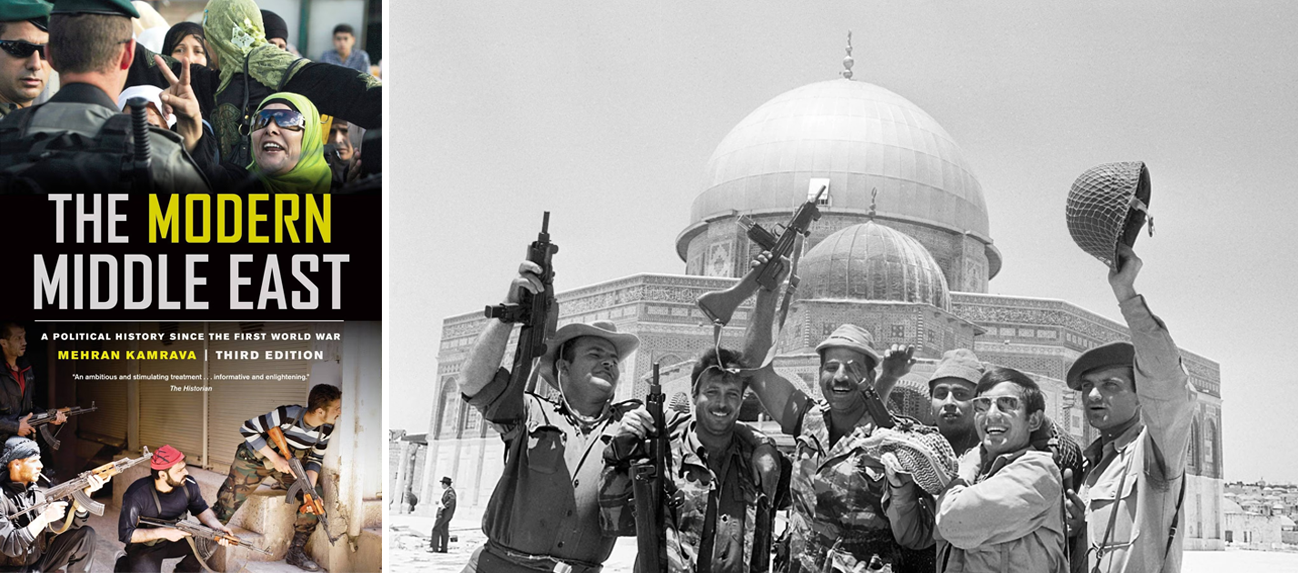

The following extracts are from “The Modern Middle East” by Kamrava (2013) — the first edition of which came out in 2005.

Zionism and the birth of Israel

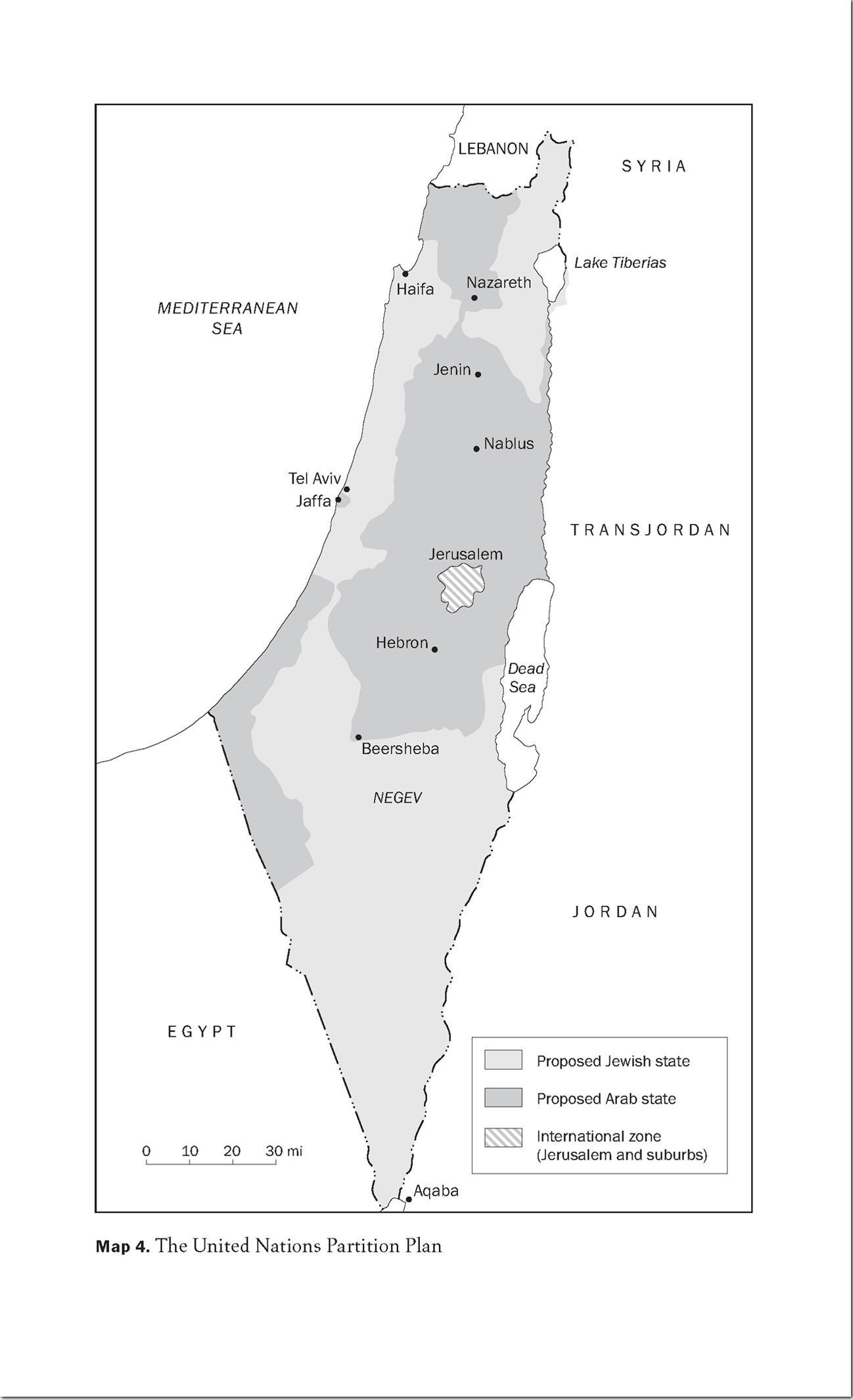

The birth of the state of Israel was predicated on three key principles: (1) the constitution of the Jews as a distinct people with a unique identity, a nation; (2) the placing of this nation on a specific territory, the biblical Eretz Israel; and (3) the territorial and juridical independence of this nation in the form of a modern country. Since the late 1800s, and especially beginning in the early 1900s and culminating in 1947–48, these principles have formed the very core of Israel. The formation of a Jewish nation was facilitated by Zionism: the nation’s precise nature and character, and even its language (Hebrew), were deliberately articulated by individuals who set out to resurrect an ancient kingdom and its people in a new, modern form. Every nation needs a territorial reference point, however abstract in definition and reality, and for the Jewish nation that reference point was in Palestine. And for the Zionist project to be successfully completed, the Jewish nation needed political and territorial independence, so Israeli statehood was declared on May 14, 1948.

The early history of Zionism reads like the determined crusade of a handful of individuals, among whom Theodor Herzl, David Ben-Gurion, and Chaim Weizmann stand out. Within a matter of years, however, what had started as individual and at times highly criticised initiatives had snowballed into a large-scale migration of European Jewry into the Promised Land. This migration was reinforced by growing, barbaric anti-Semitism and Jewish persecution, first in Russia, then in eastern and central Europe, and eventually in Germany. Although Zionism reached its most articulate and organised manifestation in nineteenth-century Europe, earlier versions of it, in the form of a belief in the chosenness of the Jewish people and their return to the land the Bible identifies as Eretz Israel, existed among Jews scattered throughout the world. This classical Zionism did not, however, provide much incentive for a return of the Jews to Palestine, as one of its central precepts was that the Jews would return to Zion only at the coming of the Messiah. Nevertheless, the Jewish diaspora had some religious ties with the existing, though very small, community of Jews in Palestine. Estimates put the total number of Jews in the early 1800s at around 2.5 to 3 million, of whom some 90 per cent lived in Europe and only about 5,000 lived in Palestine. Palestine itself had an approximate population of between 250,000 and 300,000, of whom an overwhelming majority were Sunni Muslim, some 25,000 to 30,000 were Christian, and an undetermined number, perhaps several thousand, were Druze.

Ironically, Zionism developed in a larger intellectual context that was initially opposed to the project of Jewish national assertion and uniqueness. Throughout the early 1800s, the dominant intellectual trend among the minority of learned European Jews who had not been consigned to the ghettos was the haskala. The haskala was a literary and cultural “enlightenment” calling for greater integration into the European cultural mainstream and reform of some of Judaism’s archaic rituals. It was, in fact, a notable assimilationist, a prominent Austrian journalist named Theodor Herzl, who, upon witnessing the anti-Semitism of the Dreyfus affair firsthand, decided that the Jews’ salvation lay in a hastened return to a territory of their own, a Zion free of prejudice and discrimination. In 1896, Herzl published a pamphlet called The Jewish State, in which he deplored the futility of assimilation, pointed to the pervasiveness of European anti-Semitism, and called for the establishment of a separate Jewish state based on Jewish identity and self-determination. The following year, in August 1897, he organized the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, which some two hundred delegates attended.

The 1967 War

The immediate causes of the 1967 War can be divided into three general categories: the highly volatile atmosphere of the region throughout 1966 and 1967, made all the more explosive by a series of bellicose statements coming out of Damascus and Cairo; the regional and international predicaments of Nasser; and the domestic political predicament of the Israeli prime minister at the time, Levi Eshkol. To begin with, there were the provocative activities of the Fedayeen. These commando raids had intensified after yet another coup in Syria in February 1966, when the new crop of ruling officers in Damascus were more sympathetic to the PLO’s main guerrilla unit, the Fatah. Adding to the tension between Israel and Syria were disputes over water resources and cultivation activities in their border areas, which had resulted in the massive aerial bombardment of Syrian villages by Israeli jets on several occasions. Toward the end of 1966, the Soviet Union, which by now had started supplying a limited number of arms to Syria, announced that Israel was amassing troops along the Syrian border in preparation for an all-out invasion.

Throughout, Nasser had hoped to avoid a military confrontation with Israel and had at times moderated his rhetoric with proclamations to that effect. His primary goal was to score a political victory at Israel’s expense by forcing the Israelis to stop their massive retaliatory attacks on Jordan and Syria. But the more he pursued this goal the more intractable and inflexible his position became, to the point that he could not go back on his statements. Ironically, this was the same predicament in which the Israeli prime minister found himself in relation to other Israeli political actors. Levi Eshkol had often been accused of being weak and indecisive by the opposition Rafi Party and by members of his own Mapai Party. Like Nasser, Eshkol was reluctant to wage war, fearing, among other things, that it might provoke retaliatory measures by the Soviet Union. But once Egypt closed the Strait of Tiran, Eshkol had no option but to act. He brought in the popular retired general Moshe Dayan as the country’s new defense minister, and, in the early hours of June 4, the Israeli cabinet voted in favor of war. At 7:30 a.m. on June 5, Israel commenced a relentless campaign of aerial assault against Egypt.

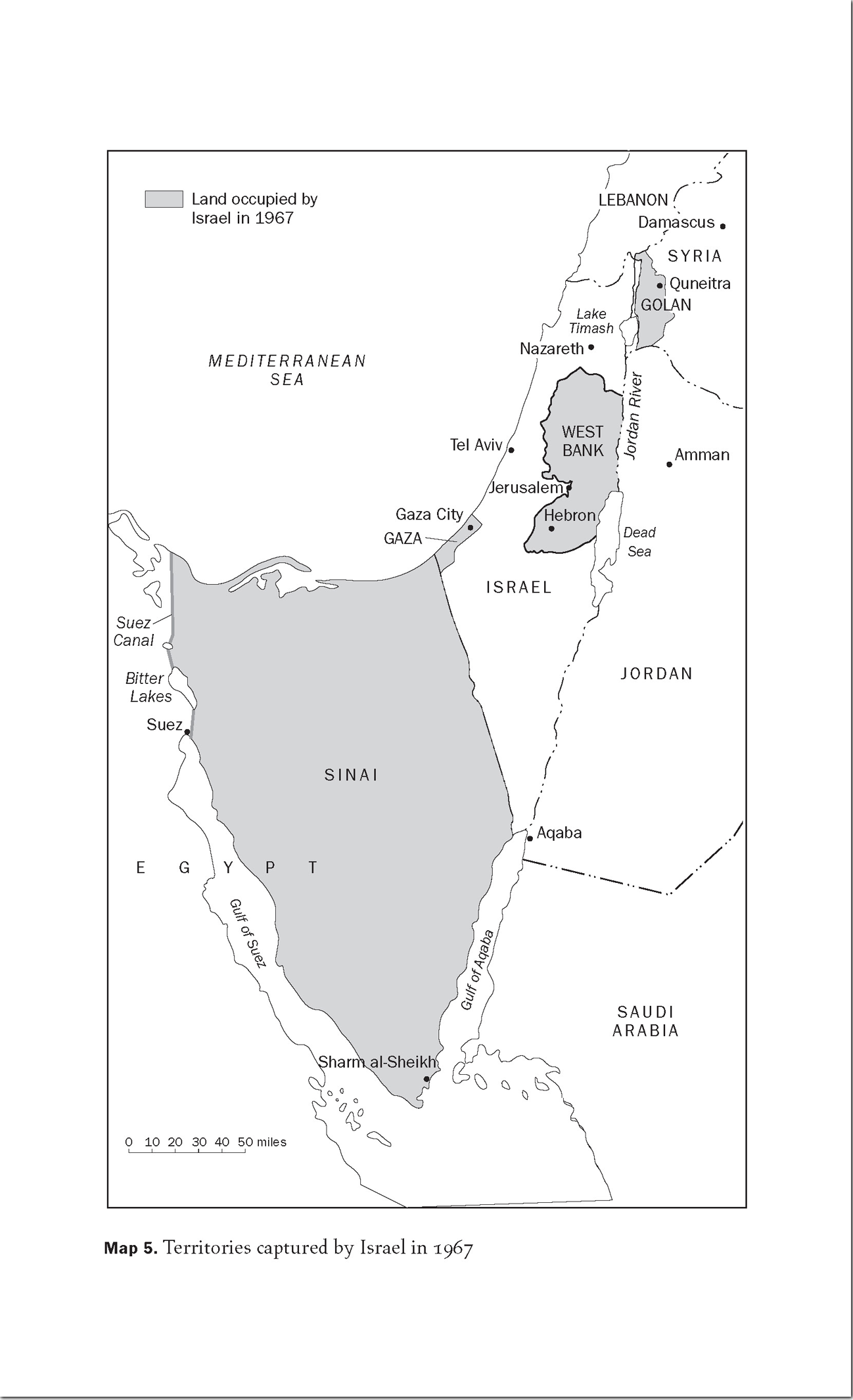

The Israeli campaign was brilliantly planned and executed. Because of Israel’s small size and population, its military doctrine had long been based on massive, surprise, offensive attacks that concentrated the greatest firepower on the biggest foe. Accordingly, within the first few hours of the war, the Israeli air force managed to destroy almost all of the Egyptian airplanes that were parked in air bases within range of its jet fighters. These included seventeen airfields and approximately 300 aircraft. By the end of the second day, the IDF claimed, it had destroyed a total of 418 aircraft from Arab countries, including 309 from Egypt, 60 from Syria, 29 from Jordan, 17 from Iraq, and 1 from Lebanon. Left with no support from the air, Egyptian forces in the Gaza Strip were overwhelmed by the end of the second day, and by the end of the third day the entire Sinai, extending as far west as the Suez Canal, was in Israeli hands. Highways leading out of the peninsula were littered with bombed-out cars and buses carrying fleeing Egyptians.

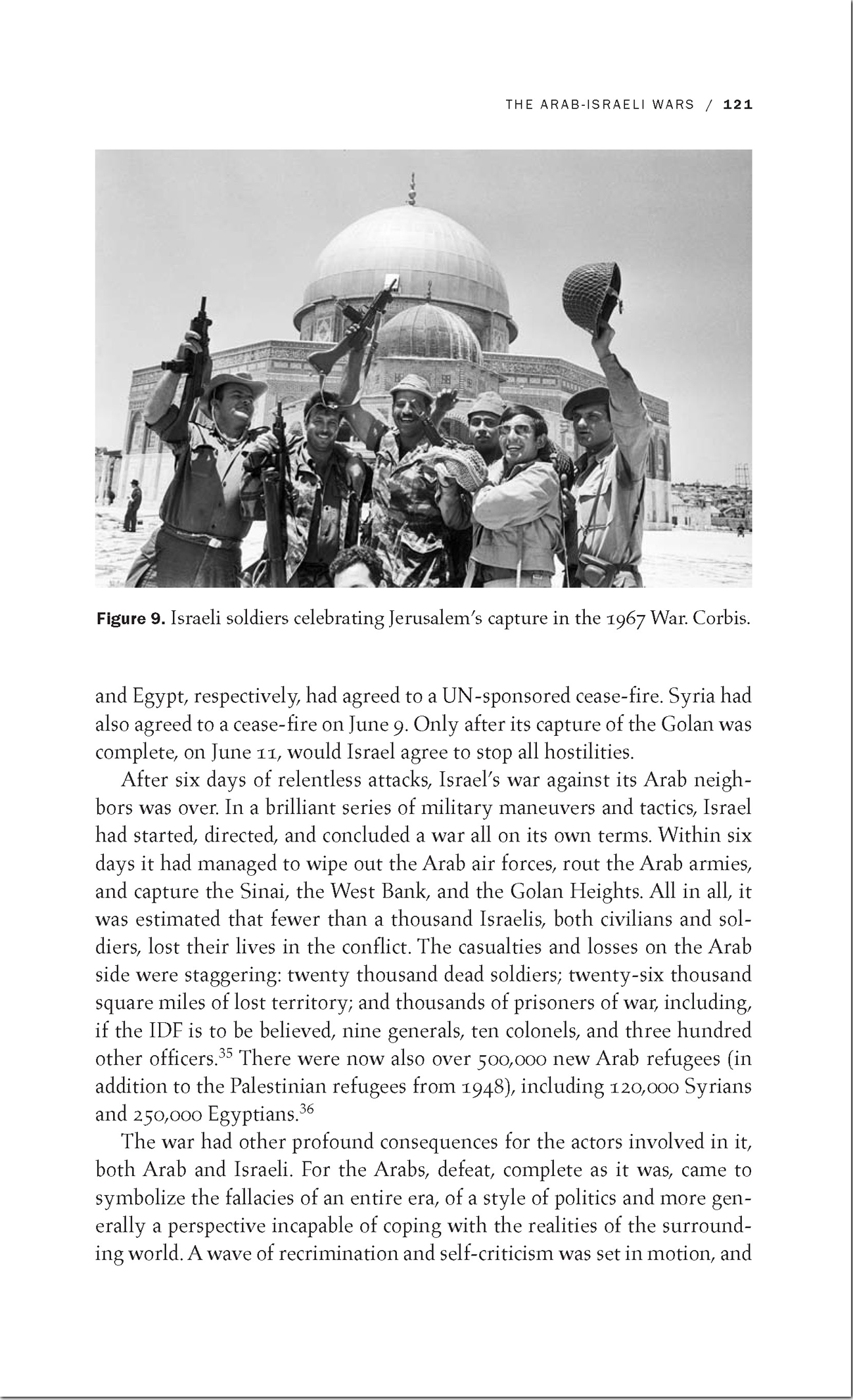

On the morning of the third day, June 7, Israeli forces turned their attention toward the Jordanian-controlled West Bank and, once again in complete control of the skies, overran Jordanian forces by that evening. The city of Jerusalem, with all its religious and historical significance for the Jews, was now in Israeli hands. For the first few days, the Syrian front had been relatively quiet, and activity there had been limited to isolated runs over Israeli territory by the remaining Syrian jets. On the fifth day of fighting, however, Israel initiated a massive attack on Syria, by the end of which it had captured the strategic Golan Heights.

The 1973 War

The Arab world entered the 1970s in a deep malaise. The nakba of 1948—the loss of Palestine—had been compounded by another catastrophe, made all the more humiliating by its boastful prelude and the endless, loud promises of liberation and victory that preceded it. The psychological wounds were deep both in the frontline states and elsewhere. A whole generation of public intellectuals emerged whose essays and stories gave popular expression to the collective anguish of their societies. Among them was the prolific and highly successful Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz, whose bitter condemnation of Nasser’s repressive police state and its military and economic failures now reached a new crescendo. Nasser’s death had done little to assuage defeatism and shattered spirits. In the Egypt he left behind, the economy barely functioned, and the War of Attrition was far from a resounding success. Not only had the Israelis captured the Sinai; they had now built a settlement on it and were claiming the peninsula as part of biblical Eretz Israel. Syria’s predicament was not much better, its ruling revolutionary generals having lost the Golan and nearly Damascus itself. Jordan’s loss of the West Bank was equally humiliating, but its war with the Fedayeen had served to strengthen the king’s hand among the East Bankers and the conservative Arab states.

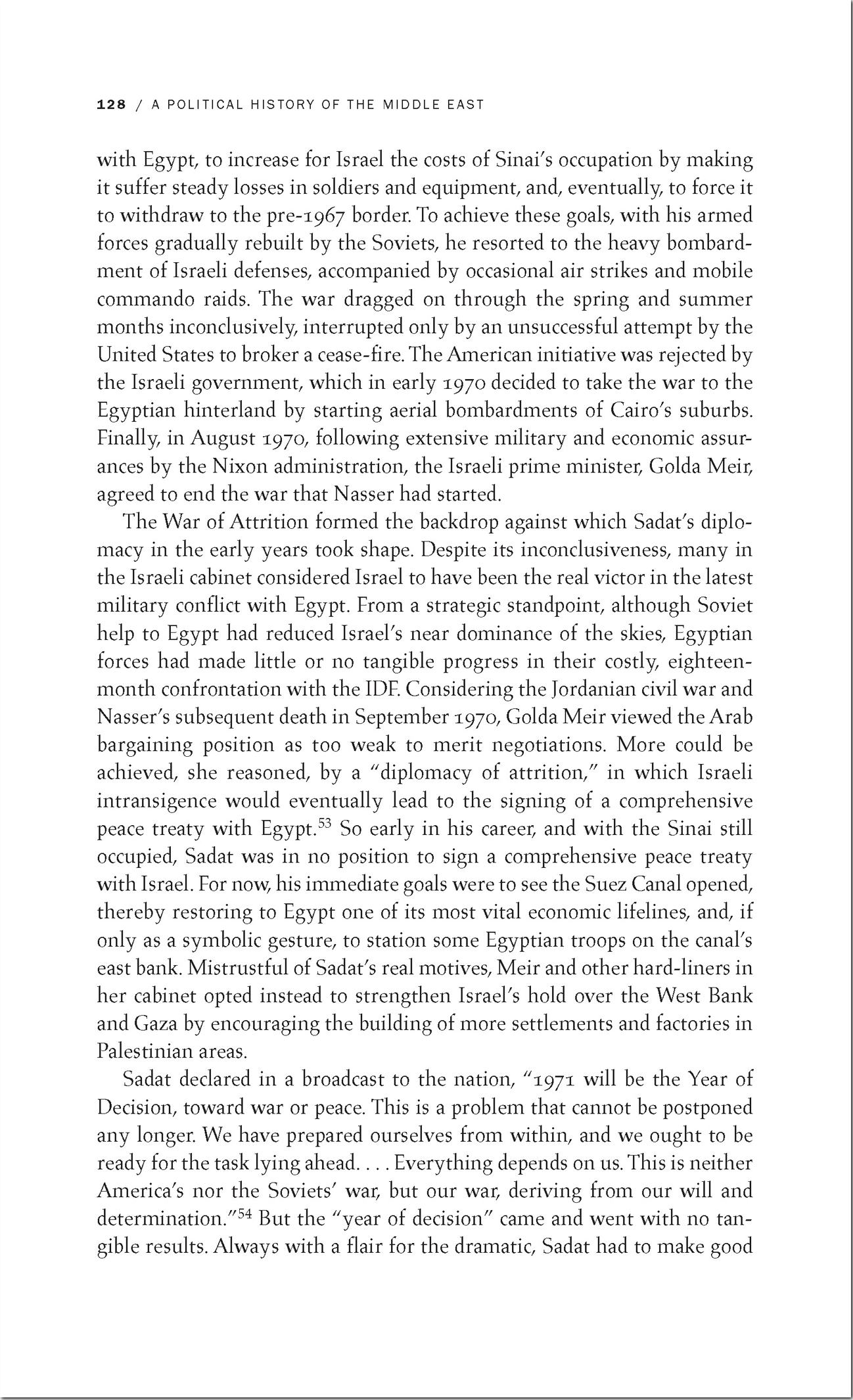

The War of Attrition formed the backdrop against which Sadat’s diplomacy in the early years took shape. Despite its inconclusiveness, many in the Israeli cabinet considered Israel to have been the real victor in the latest military conflict with Egypt. From a strategic standpoint, although Soviet help to Egypt had reduced Israel’s near dominance of the skies, Egyptian forces had made little or no tangible progress in their costly, eighteen-month confrontation with the IDF. Considering the Jordanian civil war and Nasser’s subsequent death in September 1970, Golda Meir viewed the Arab bargaining position as too weak to merit negotiations. More could be achieved, she reasoned, by a “diplomacy of attrition,” in which Israeli intransigence would eventually lead to the signing of a comprehensive peace treaty with Egypt. So early in his career, and with the Sinai still occupied, Sadat was in no position to sign a comprehensive peace treaty with Israel. For now, his immediate goals were to see the Suez Canal opened, thereby restoring to Egypt one of its most vital economic lifelines, and, if only as a symbolic gesture, to station some Egyptian troops on the canal’s east bank. Mistrustful of Sadat’s real motives, Meir and other hard-liners in her cabinet opted instead to strengthen Israel’s hold over the West Bank and Gaza by encouraging the building of more settlements and factories in Palestinian areas.

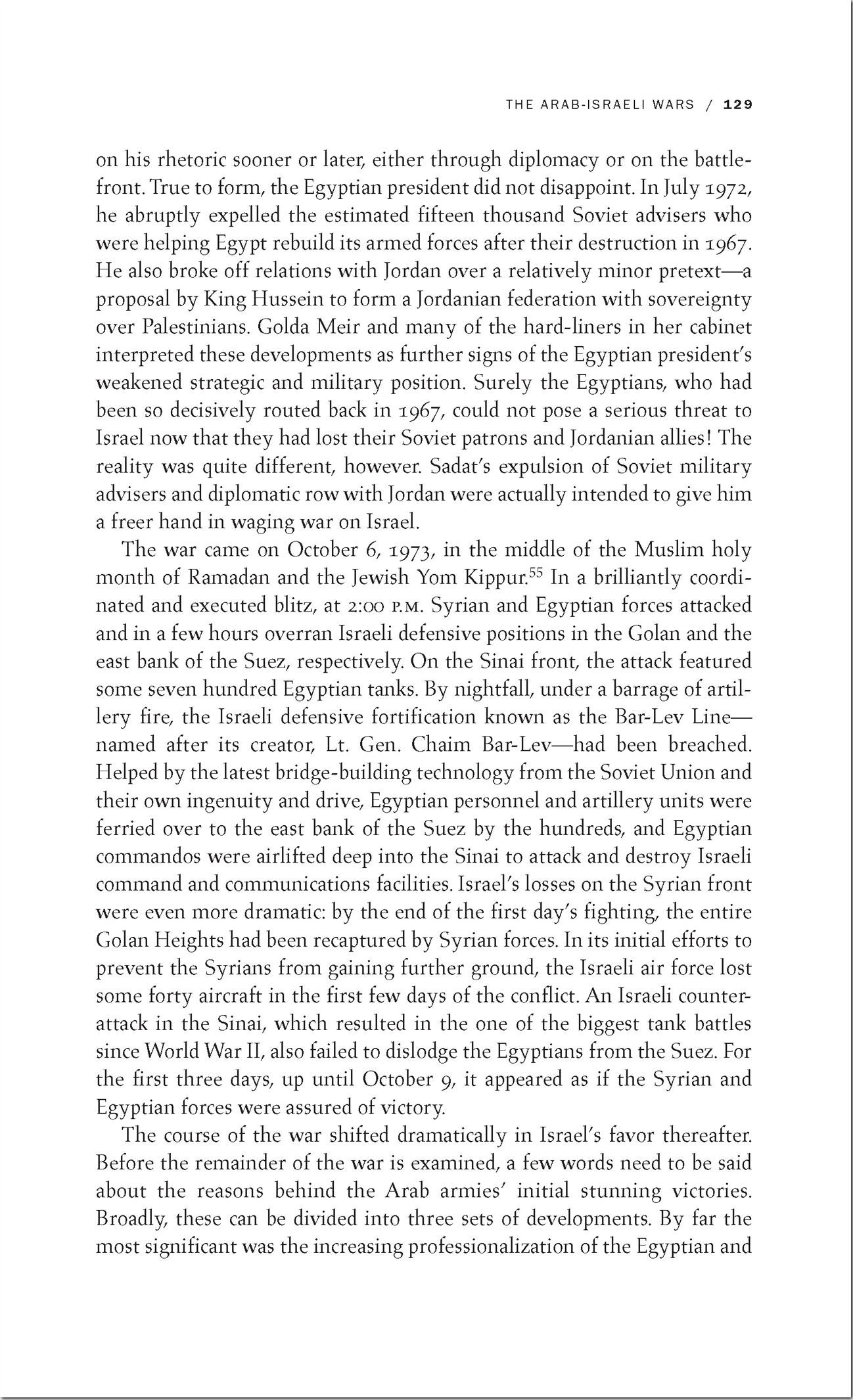

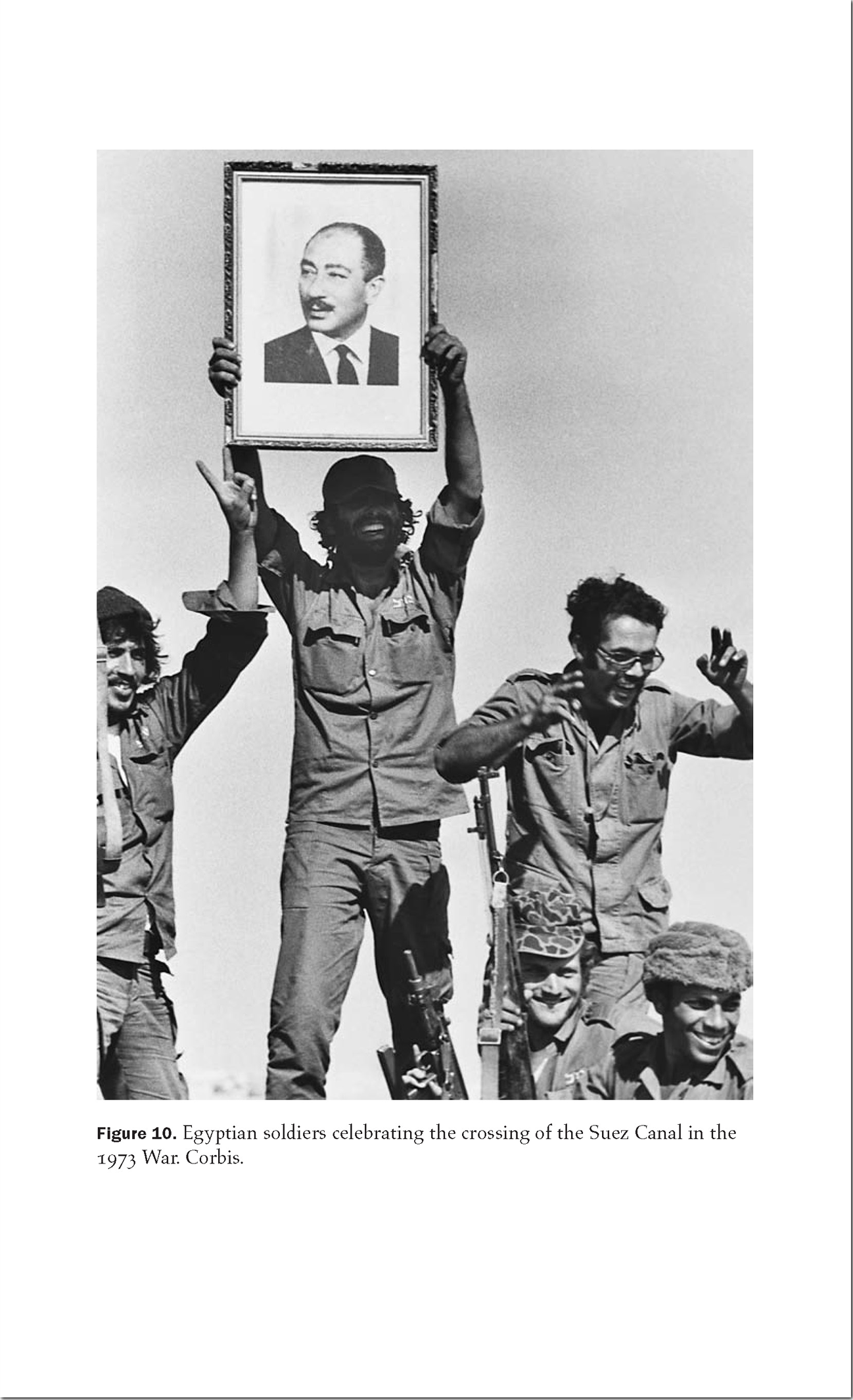

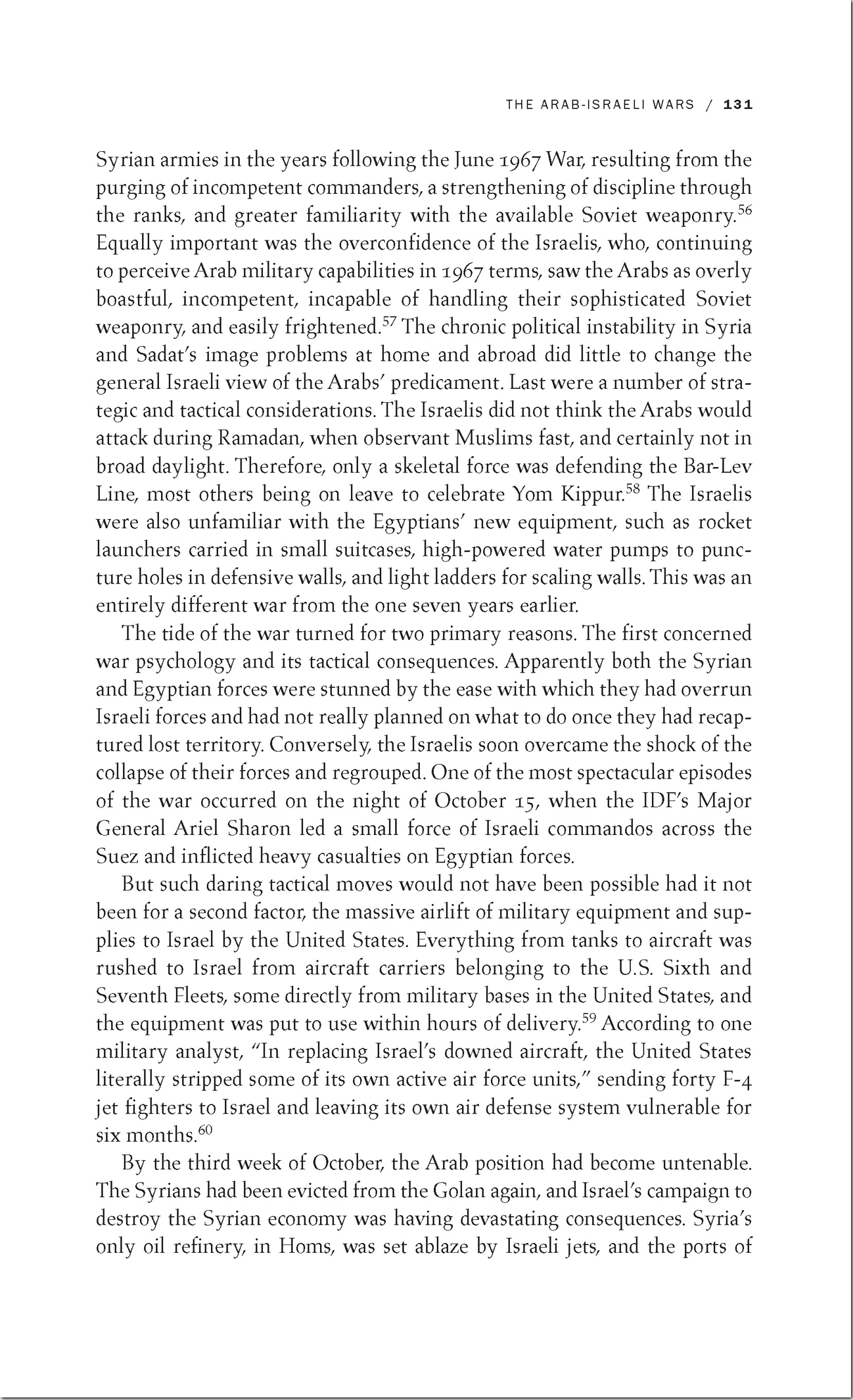

The war came on October 6, 1973, in the middle of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan and the Jewish Yom Kippur. In a brilliantly coordinated and executed blitz, at 2:00 p.m. Syrian and Egyptian forces attacked and in a few hours overran Israeli defensive positions in the Golan and the east bank of the Suez, respectively. On the Sinai front, the attack featured some seven hundred Egyptian tanks. By nightfall, under a barrage of artillery fire, the Israeli defensive fortification known as the Bar-Lev Line—named after its creator, Lt. Gen. Chaim Bar-Lev—had been breached. Helped by the latest bridge-building technology from the Soviet Union and their own ingenuity and drive, Egyptian personnel and artillery units were ferried over to the east bank of the Suez by the hundreds, and Egyptian commandos were airlifted deep into the Sinai to attack and destroy Israeli command and communications facilities. Israel’s losses on the Syrian front were even more dramatic: by the end of the first day’s fighting, the entire Golan Heights had been recaptured by Syrian forces. In its initial efforts to prevent the Syrians from gaining further ground, the Israeli air force lost some forty aircraft in the first few days of the conflict. An Israeli counterattack in the Sinai, which resulted in the one of the biggest tank battles since World War II, also failed to dislodge the Egyptians from the Suez. For the first three days, up until October 9, it appeared as if the Syrian and Egyptian forces were assured of victory.

The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

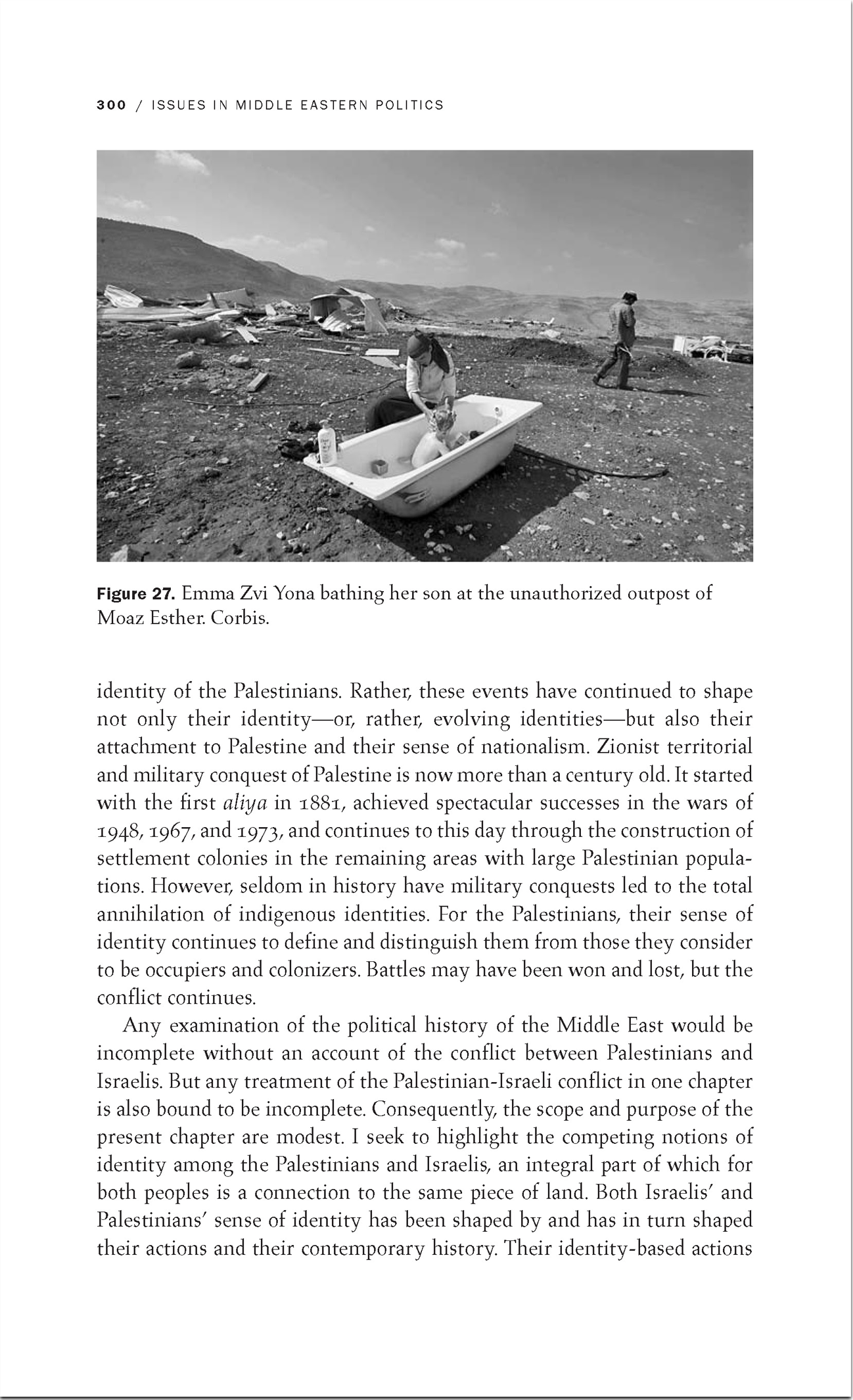

One of the most vexing problems in the political history of the modern Middle East, and indeed of the larger global community, has been the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. Through the vicissitudes of history and the vagaries of power politics, both international and domestic, these two peoples have come to inhabit the same piece of territory. We have, essentially, as the late Deborah Gerner put it, “one land, two peoples.” Over the years, they have fought, cajoled, killed, and harassed each other. And they have been unwilling or unable to find ways of “sharing the promised land.” An overwhelming majority of peoples on both sides have come to view the other as “the enemy,” dehumanized and devoid of rights or legitimacy. In defending a cause they view as singularly righteous and just, each side has inflicted pain and misery on the other. Today, neither side has a monopoly over fear of violence from the other.

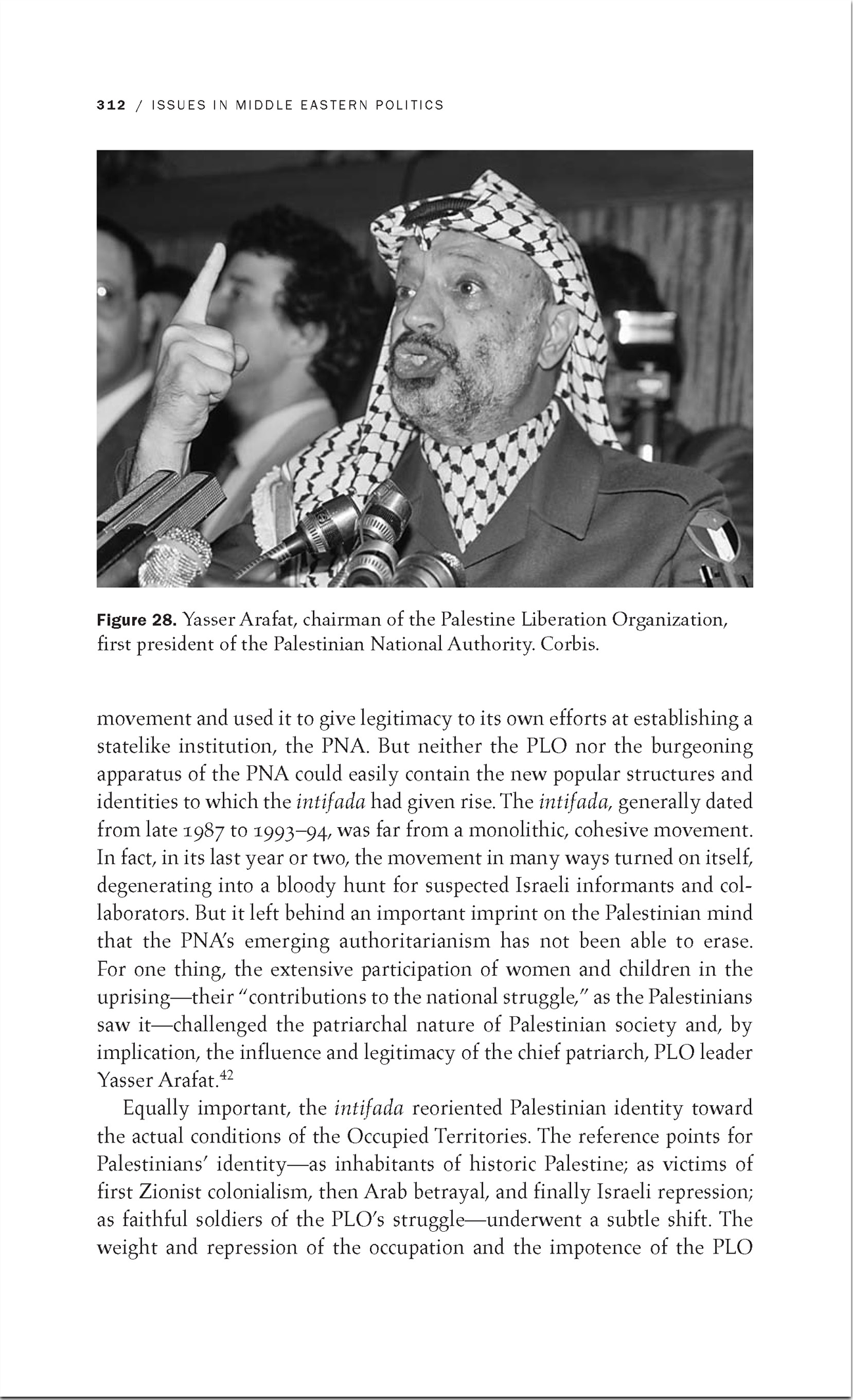

History has been kind to neither the Zionists nor the Palestinians. Both communities have been scattered throughout the world at different times and forced to live in exile. In the diaspora, the Jews faced persecution and the threat of annihilation. The Palestinians, many of whom still live outside Palestine, are frequently used by Middle Eastern despots who claim the cause of Palestinian liberation for their own narrow, domestic political purposes. Since 1948, when the state of Israel was created and geographic Palestine ceased to exist, Israel has had the upper hand politically and militarily.

Imagery

References

Gerner, D. J. (1991). One Land, Two Peoples: The Conflict Over Palestine. Avalon Publishing.

Hiro, D. (1999). Sharing the Promised Land: A Tale of Israelis and Palestinians. Olive Branch Press.

Kamrava, M. (2013). The Modern Middle East: A Political History since the First World War (3 ed.). University of California Press.