First published in:

Sinclair, I. (2023, March 8). Why do the US and Britain still claim the invasion of Iraq was to spread democracy? Morning Star. https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/f/why-do-us-britain-claim-iraq-invasion-was-to-spread-democracy

🖨 Print-friendly PDF

Why do the US and Britain still claim the invasion of Iraq was to spread democracy?

The hostility towards elections and democracy by the US-British military administration that brutally overran the nation in 2003 was well documented at the time — as was the mass movement for free elections, writes

A little late to the party, I recently watched Once Upon A Time In Iraq, the BBC’s 2020 five-part documentary series about the US-British invasion and occupation of the Middle East nation.

During the episode about the capture of Iraqi president Saddam Hussein in December 2003, the narrator noted: “Though Iraq was still governed by the [US-led] coalition, the intention was to hold democratic elections as soon as possible.”

This fits with the common understanding of the Iraq War amongst the media, academic and political elites. For example, speaking on the BBC News at 10 in 2005, correspondent Paul Wood stated: “The coalition came to Iraq in the first place to bring democracy and human rights.”

Likewise, writing in the Guardian in 2013, the esteemed University of Cambridge Professor David Runciman claimed: “The wars fought after 2001 in Afghanistan and Iraq were designed… to spread the merits of democracy.”

No doubt similarly benign framing of the West’s intentions and actions will be repeated as we approach the 20th anniversary of the invasion on March 20 2003.

But is it true? As always it is essential to compare the narrative pumped out by corporate and state-affiliated media with the historical record.

We know that soon after US-led forces had taken control of the country, Iraqis began holding local elections. However, in June 2003, the Washington Post reported “US military commanders have ordered a halt to local elections and self-rule in provincial cities and towns across Iraq, choosing instead to install their own handpicked mayors and administrators, many of whom are former Iraqi military leaders.”

The report goes on to quote Paul Bremer, the chief US administrator in Iraq: “I’m not opposed to [self-rule], but I want to do it in a way that takes care of our concerns… in a postwar situation like this, if you start holding elections… it’s often the best-organised who win, and the best-organised right now are the former Baathists and to some extent the Islamists.”

On the national level, Professor Toby Dodge, who advised US General David Petraeus in Iraq, notes one of the first decisions Bremer made, after he arrived in Baghdad in May 2003, “was to delay moves towards delegating responsibility to a leadership council” composed of exiled politicians.

Writing in his 2005 book, Iraq’s Future, the establishment-friendly British academic goes on to explain “this careful, incremental but largely undemocratic approach was set aside with the arrival of UN special representative for Iraq, Vieira de Mello” who “persuaded Bremer that a governing body of Iraqis should be set up to act as a repository of Iraqi sovereignty.”

Accordingly, on July 13 2003 the Iraqi Governing Council (IGC) was set up. Dodge notes the membership “was chosen by Bremer after extended negotiations between the CPA [the US Coalition Provisional Authority], Vieira de Mello and the seven dominant, formerly exiled parties.” The IGC would “establish a constitutional process,” Bremer said at the time.

However, the Americans had a serious problem on their hands. In late June 2003 the most senior Shia religious leader in Iraq, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, issued a fatwa (a religious edict) condemning the US plans as “fundamentally unacceptable.”

“The occupation officials do not enjoy the authority to appoint the members of a council that would write the constitution,” he said. Instead, he called for a general election “so that every eligible Iraqi can choose someone to represent him at the constitutional convention that will write the constitution” which would then be put to a public referendum.

“With no way around the fatwa, and with escalating American casualties creating pressure on President Bush,” the Washington Post reported in November 2003 that Bremer “dumped his original plan in favour of an arrangement that would bestow sovereignty on a provisional government before a constitution is drafted.”

This new plan, known as the November 15 Agreement, was based on a complex process of caucuses. A 2005 briefing from peace group Justice Not Vengeance (JNV) explained just how anti-democratic the proposal was: “US-appointed politicians would select a committee in each province which would select a group of politically acceptable local worthies, which in turn would select a representative… to go forward to the national assembly” which would “then be allowed to elect a provisional government.”

In response, Sistani made another public intervention, repeating his demand that direct elections — not a system of regional caucuses — should select a transitional government. After the US refused to concede, the Shia clerical establishment escalated their pro-democracy campaign, organising street demonstrations in January 2004.

100,000 people protested in Baghdad and 30,000 in Basra, with news reports recording crowds chanting: “Yes, yes to elections, no, no to occupation” and banners with slogans such as “we refuse any constitution that is not elected by the Iraqi people.”

Under pressure, the US relented, agreeing in March 2004 to hold national elections in January 2005 to a Transitional National Assembly which was mandated to draft a new constitution.

The campaigning group Voices In The Wilderness UK summarised events in a 2004 briefing: “Since the invasion, the US has consistently stalled on one-person-one-vote elections” seeking instead to “put democracy on hold until it can be safely managed,” as Salim Lone, director of communications for the UN in Iraq until autumn 2003, wrote in April 2004.

Why? “An elected government that reflected Iraqi popular [opinion] would kick US troops out of the country and is unlikely to be sufficiently amenable to the interests of Western oil companies or take an ‘acceptable’ position on the Israel-Palestine conflict,” Voices In The Wilderness UK explained.

For example, a secret 2005 nationwide poll of Iraqis conducted by the UK Ministry of Defence found 82 per cent “strongly opposed” to the presence of the US-led coalition forces, with 45 per cent of respondents saying they believed attacks against British and American troops were justified.

It is worth pausing briefly to consider two aspects of the struggle for democracy in Iraq. First, the Sistani-led movement in Iraq was, as US dissident intellectual Noam Chomsky argued in 2005, “One of the major triumphs of non-violent resistance that I know of.”

And second, it was a senior Iraqi Shia cleric who championed democratic elections in the face of strong opposition from the US — the “heartland of democracy,” according to the Financial Times’s Martin Wolf.

It is also worth remembering, as activist group JNV noted in 2005, that president George W Bush’s ultimatum days before the invasion was simply that “Saddam Hussein and his sons must leave Iraq within 48 hours.” This was about “encouraging a last-minute coup more than the Iraqi leader’s departure from Baghdad,” the Financial Times reported at the time. In short, the US-British plan was not free elections via “regime change” but “regime stabilisation, leadership change,” JNV argued.

This resonates with the analysis of Middle East expert Jane Kinninmont. Addressing the argument the West invaded Iraq to spread democracy, in a 2013 Chatham House report she argued: “This is asserted despite the long history of Anglo-American great-power involvement in the Middle East, which has, for the most part, not involved an effort to democratise the region.”

In reality “the general trend has been to either support authoritarian rulers who were already in place or to participate in the active consolidation of authoritarian rule… as long as these rulers have been seen as supporting Western interests more than popularly elected governments would.”

This thesis is not short of shameful examples — from the West’s enduring support for the Gulf monarchies in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, Oman, Qatar and Kuwait, to the strong backing given to Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt before both dictators were overthrown in 2011.

📕 “Oil’s corruptive capacity” →

Back to Iraq: though far from perfect, national elections have taken place since 2003. But while the US has been quick to take the credit, the evidence shows any democratic gains won in Iraq in the immediate years after the invasion were made despite, not because of, the US and their British lackey.

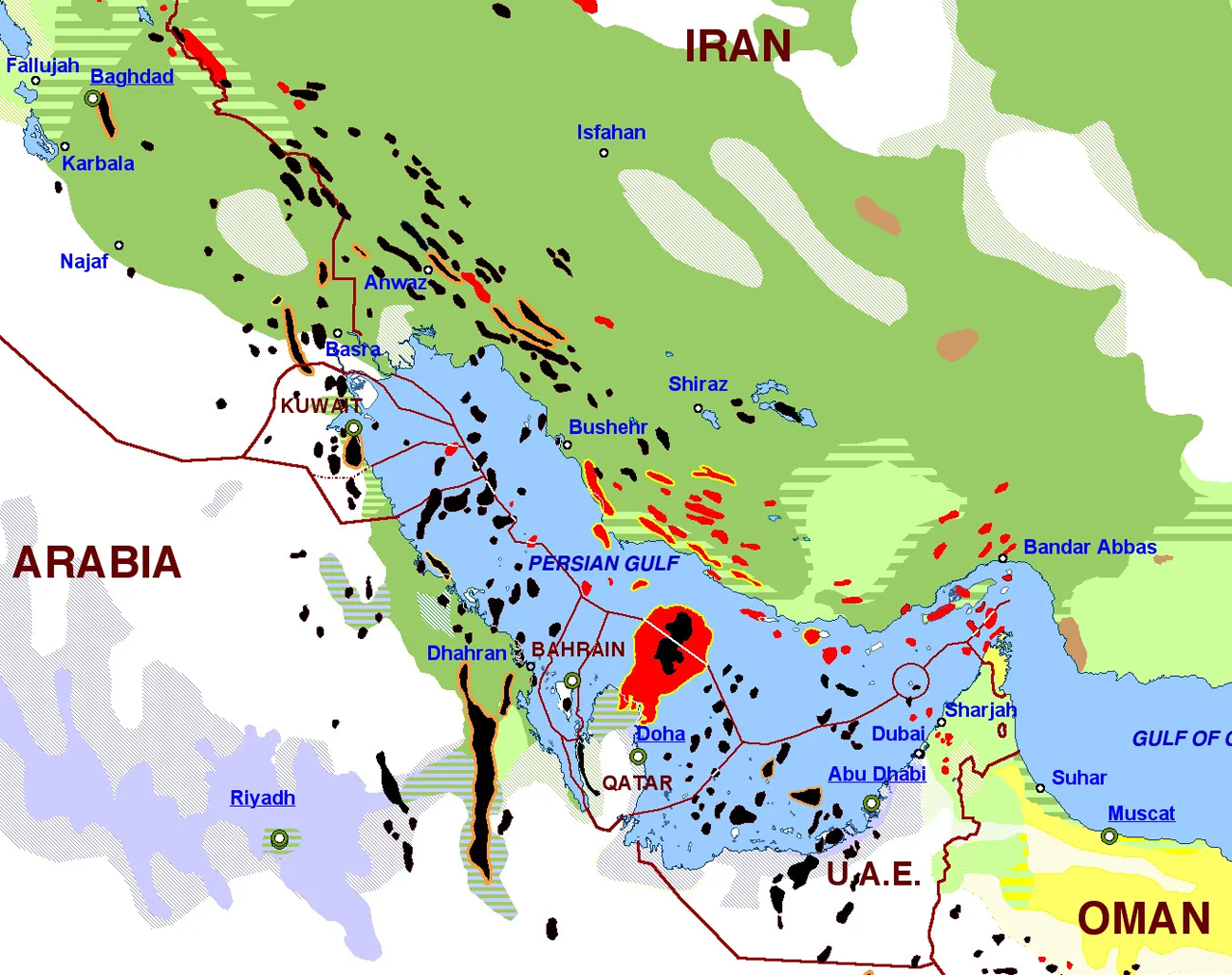

Indeed, an October 2003 Gallup poll of Baghdad residents makes instructive reading. Fully 1 per cent of respondents agreed with the BBC and Runciman that a desire to establish democracy was the main intention of the US invasion. In contrast, 43 per cent of respondents said the invasion’s principal objective was Iraq’s oil reserves.