Writing in 2014, Fanar Haddad says, no other event—not even the Iranian Revolution of 1979—has had “as momentous and detrimental an effect on sectarian relations in the Middle East as the war on and occupation of Iraq in 2003” (p. 67). And lest we forget, that debacle was not about the spreading of democracy in any way, shape or form. As Ian Sinclair reminds us in an excellent piece (see: WMD? or actually oil) an October 2003 Gallup poll of Iraqis residing in Baghdad found a full one per cent (yes, 1%) agreed with the premise that the US/UK desire to establish democracy was the main motivating factor for the invasion, while “43 per cent of respondents said the invasion’s principal objective was Iraq’s oil reserves.”

Oil Blessings & The U.S. Dollar

📕 “Maps, aesthetically scientific” →

📕 “Oil’s corruptive capacity” →

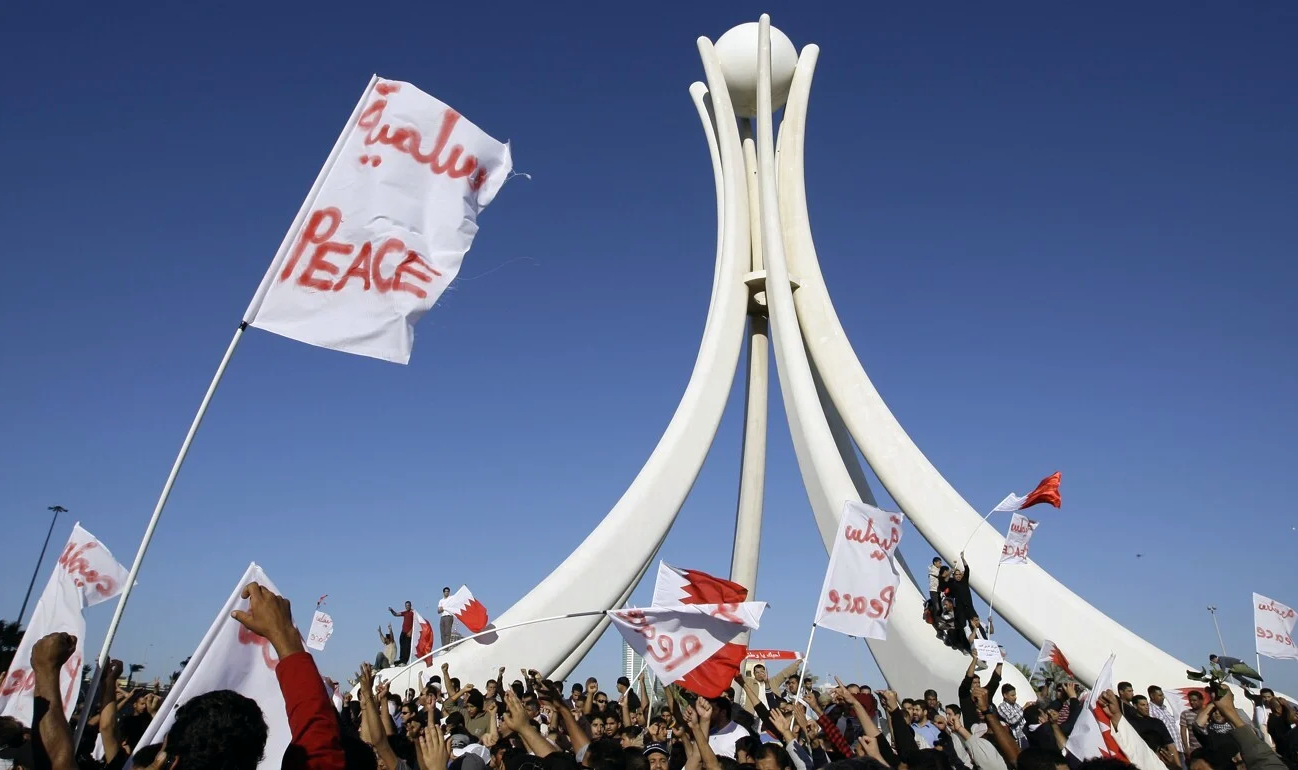

Matthiesen (2013) was in Bahrain in February 2011 when the Kingdom’s “Arab Spring” protests began, and records the initially peaceful character of the demonstrations, and not only peaceful but explicitly anti-sectarian (“neither Shia nor Sunni” the demonstrators chanted at the start). It is easy to forget now, as Jones (2015, p. 242) writes, “there was a spirit of optimism at that point, and many hoped Crown Prince Salman would successfully negotiate a compromise” (i.e., transition to a more accountable regime).

This opportunity evaporated within a month, on the 14th of March 2011, with the intervention of Saudi troops across the causeway. As Jones (2015) writes in his review of Matthiesen’s work, “it provides an account of Bahrain’s counter-revolution, the National Dialogue and the establishment of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry.” Matthiesen notes that the head of the commission had said, “you can’t say justice has been done when calling for Bahrain to be a republic gets you a life sentence and an officer who repeatedly fires on an unarmed man at close range gets seven years.”

Potter (2014) writes that in the wake of the Arab Spring, “in the Persian Gulf monarchies, there was a continuing standoff between Sunni and Shia in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, and a widespread fear [be it imagined or tangible] of Iranian irredentism.” Jones (2015, p. 243) suggests that the central thesis of Matthiesen (213) is that some such monarchies have “deliberately stoked sectarianism, both as a means to fight the perceived Shia threat, as well as to divide and rule.” Proving intent is difficult acknowledges Jones; “Who can say whether leadership is foolish or wicked, or indeed both? But the outcome is the same.”

The Schism

The schism (divide or split) between Sunni and Shia Islam emerged after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632, and disputes arose over who should shepherd the new and rapidly growing faith. Some believed that a new leader should be chosen by consensus; others thought that only the prophet’s descendants should become caliph. Muslims who wanted to select his successor, or Caliph, by following the traditional Arab custom (Sunna, ‘the way’) formed into a group known as Sunnis and elected Abu Bakr, a companion of Mohammed, to be the first caliph, or leader of the Islamic community. Others insisted the Prophet had designated his cousin and son-in-law Ali as his legitimate heir. This group was called Shia Ali, or ‘Party of Ali,’ (from which the word ‘Shia’ is now derived).

While the main responsibility of Sunni Caliphs was to maintain law and order in the Muslim realm, as descendants of the Prophet, Shia Imams (spiritual leaders) also provided religious guidance and were/are considered infallible — see, e.g., Axworthy (2017), Harney (2016) and Hubbard (2016). According to The Council on Foreign Relations (2023), Shias believe that Ali and his descendants are part of a divine order while Sunnis are opposed to political succession based on Mohammed’s bloodline.

Words matter

Framing the term “sectarianism” is fraught with both controversy and difficulty. It stems from the notion of a sect: a group with distinctive religious, political, or philosophical point of view and/or set of (ritualistic) practices. Most often the term has a religious connotation, such as a small group (minority) that has broken away from “orthodox” (mainstream) beliefs. According to Potter (2014, p. 2) Western writers typically, and mistakenly, characterise Sunnis as “orthodox” Muslims, and Shia as being “heterodox.” Sectarianism has come to have a negative connotation, denoting a group that sets itself off from society and thereby raises tensions. Haddad (2014, p. 67) notes that the term “sectarianism” does not have a definitive meaning, and prefers to view such groups in Iraq as “competing subnational mass-group identities.” It follows then that ‘sectarian’ identities, much like ethnic ones, are constantly changing and being both renegotiated (Smith, 2000) and reimagined (Anderson, 1983). I agree with the sentiments of Haddad (2014), until scholars are able to satisfactorily define “sectarianism,” a more coherent way of addressing the issue would be to use the term “sectarian” followed by the appropriate suffix: sectarian hate; sectarian unity; sectarian discrimination, and so forth.

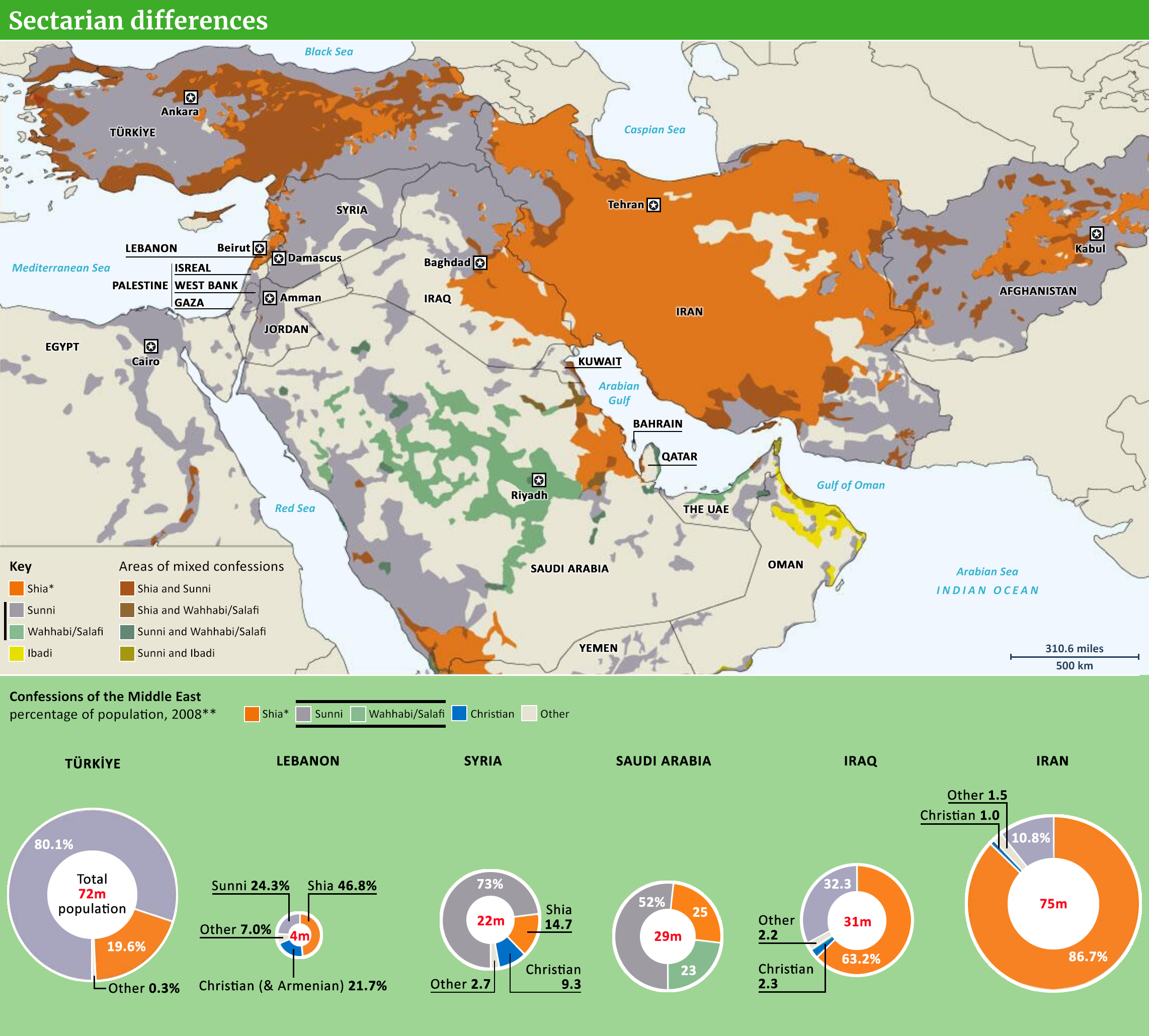

The map below gives details on the confessional divides on and around the Arabian peninsular. Although the data used to compile the map is dated the work is based on that carried out by Dr Michael Izady) and later used by The Financial Times of London is the latest as far as know. The Table that follows gives more recent figures but not geographical spread. As will become apparent when consulting the table and notes, the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) relies heavily on the U.S. State Department’s annual International Religious Freedom Reports (that are submitted to the House of Congress annually in accordance with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998). Those said reports paint a common theme: virtually all Gulf citizens are Muslim, but official demographics published by these countries do not delineate along confessional lines so, local media and think-tank reporting is relied upon.

To gain a deeper understanding of the region’s “sectarian” politics the following are worth investigating: Potter (2014) and Matthiesen (2013).

* Includes gnostic Alawites & Alevis. ** Dated; see Table below. Expand map.

* Includes gnostic Alawites & Alevis. ** Dated; see Table below. Expand map.

Table: Religions in 2023 (%)

| Country | Sunni | Shia | Other |

| Bahrain a | 28 | 54 | 18 |

| Kuwait b | 66 | 17 | 17 |

| Oman c | 47 | 7 | 46 |

| Qatar d | 66 | 12 | 22 |

| Saudi Arabia e | 81 | 9 | 10 |

| The UAE f | 67 | 7 | 26 |

| Iran | 17 | 81 | 1 |

| Iraq | 35 | 61 | 4 |

| Jordan | 93 | 2 | 5 |

| Egypt | 90 | < 1 | 10 |

| Yemen | 44 | 55 | 1 |

a

The US state department’s 2023 IRF report on Bahrain estimates the total population to be approximately 1.5 million with Bahrainis numbering around 720,000 (June 2023 – compare with Arabian Gulf data). The Bahraini government does not publish statistics that delineate its the Shia and Sunni Muslim populations but, “estimates from NGOs and the Shia community state Shia Muslims represent a majority (55 to 70 per cent).”

b

The IRF Report on Kuwait The U.S. government estimates the total population at 3.2 million (midyear 2022). U.S. government figures also cite the Public Authority for Civil Information (PACI), a local government agency, which reports that the country’s total population was 4.8 million in 2023. As of June, PACI reported there were 1.5 million citizens and 3.3 million noncitizens. PACI estimates 74.7 percent of citizens and noncitizens are Muslims. The national census does not distinguish between Shia and Sunni Muslims. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the media estimate approximately 70 percent of citizens are Sunni Muslims, while the remaining 30 percent are Shia Muslims (including Ahmadi and Ismaili Muslims, whom the government counts as Shia).

c

The IRF Report on Oman states that around 41 per cent of the Sultanate’s population constitutes foreign guest workers. Regarding the national Omani citizens, it is estimated that 45 per cent are Sunni, 45 per cent are Ibadi and most of the remainder are Shia (like its neighbours, the Omani government does not directly publish religious confession breakdowns). Note that the ARDA percentages in the Table above differ from those provided by the IRF.

d

According to the IRF Report on Qatar, as of 2023 Qataris made up approximately 11 per cent of the country’s total population and that “most citizens are Sunni, and almost all others are Shia.”

e

The IRF Report on Saudi Arabia estimates that around 85 per cent of Saudis are Sunni. The remainder are Shia, but in the oil-rich Eastern provinces of the country, this latter group comprises a substantial fraction (see: Oil’s corruptive capacity).

f

The 2023 IRF Report on the UAE suggests that approximately 11 per cent of the country’s population are Emiratis, of whom more than 85 per cent are Sunni. Most of the remainder, according to the report are are Shia citizens, “who are concentrated in the Emirates of Dubai and Sharjah.”

The myth of a Sunni-Shia War

https://medium.com/@AbdulAzim/the-myth-of-a-sunni-shia-war-554c2d5bd82e

Abdul-Azim Ahmed

October 17, 2014

The narrative of a Sunni-Shia war is so prevalent it is now accepted without challenge – but Abdul-Azim Ahmed argues it is misleading to the point of inaccuracy.

‘But what about the great divide that is currently ripping apart the Middle-East?’

The question was asked to me at the launch of an exhibition about Muslim and Jewish relations at Cardiff University. The questioner was an elderly gentleman, clearly an academic, who had just finished reading part of the exhibition. I asked him to clarify.

‘The Sunni and Shia divide, that tore Islam asunder from the earliest days after the Prophet up to today’ he explained. As we continued our conversation, I discovered that this Professor of Chemistry felt the exhibition was intellectually dishonest for not acknowledging the impact of the division.

It is a view that is increasingly common. Namely, that much of the conflict in the Middle-East and to some extent North Africa, can be summarised as a struggle between warring factions within Islam -the Sunni majority and the Shia minority. You can read about it in respectable titles such as TIME magazine, The Spectator, even the New Statesman – all of whom covered it with front-page features, illustrating the conflict with stereotypical images of Arabs that tapped into centuries of Orientalist depictions of Muslims.

The Sunni versus Shia narrative has been featured in almost every newspaper I cared to check. Most recently, The Independent published a piece with the headline ‘The vicious schism between Sunni and Shia has been poisoning Islam for 1,400 years – and it’s getting worse’. The article of course mentioned the idea of the ‘Shia Crescent’ (a crescent-shaped area of land where there is a high Shia population) that is so ubiquitous in analysis it is almost cliché, not to mention being almost entirely useless as a tool for understanding geopolitical relationships.

The Sunni-Shia thesis essentially posits that a 7th century conflict of leadership amongst Muslims is the source of current Middle-Eastern unrest. The conflict led to two distinct theological groups emerging, the Ahlus Sunnah wal Jamaah (People of the Example of the Prophet and the Majority – conveniently shortened to ‘Sunni’) and the Shi’at Ali (the Party of Ali or ‘Shia’). The story goes that the two groups have been locked in a 1400 year conflict that has spanned continents, nation states and empires, and reaches its modern zenith in Syria, Bahrain, and the cold war between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

The problem with this thesis is that it is wrong. Not just partially wrong (as political analysis is, of course, always subject to interpretation) but so misleading, so inaccurate, and so detached from reality that it cannot be described as anything other than myth.

Even more problematic is that this myth has become so pervasive that gentlemen such as the professor I met consider it inconceivable to talk of Islam without talking of the Sunni-Shia conflict. Religious journalism has never been so dismally let down.

An Ancient Conflict?

The most common myth associated with the Sunni-Shia thesis is that Islam has been rent asunder by the sectarian conflict since its inception. This is simply reading history through solely modern eyes.

There was of course a dispute about religious authority following the death of the Prophet Muhammad. Historical specificities aside, the Sunni and Shia divide was largely a political one. There were no direct theological implications until the 10th and 11th centuries when orthodoxies began to settle and a Sunni Islam became distinct from a Shia Islam, led in separate directions as they developed distinct legal and interpretative traditions.

The lines have always been blurred between Sunnis and Shias, and they are so blurred that it is often difficult to make a distinction at all in the early centuries of Islam – for example, both Sunnis and Shias celebrate and claim for their own many of the same historical figures. Many of the Imams of Twelver Shiism are regarded as pious and orthodox by Sunni Muslims. Identities were fluid too, so that the revolution that put the Abbasid’s in power in the 9th century started as strongly Shia but ended as ardently Sunni.

Paul Vallely, writing in The Independent, argued that ‘the division between the two factions is older and deeper even than the tensions between Protestants and Catholics’. He is certainly correct that the division is older. But deeper? More significant? Certainly not historically, nor theologically. Sunni and Shia divergence in practice is really only intelligible to those very familiar with Islam in general.

There are differences in notions of orthopraxis (how and when to pray, for example). There are differences too in how scripture is assessed and interpreted – important yes, but historically, these have been the topic of scholarly dispute rather than military dispute. There have been times when Sunnis and Shias fought against each (the 7th century not being one of those times, importantly), but there have also been times when Shia have fought against Shia and Sunni have fought against Sunni.

The argument that Sunnis and Shias have been at each others throats since the 7th century is wrong in every way possible.

A War of Two Nations

So, if the claim of a Sunni-Shia conflict is historically incorrect, what about in the modern context?

What journalists and those who buy in to the Sunni-Shia narrative are doing is essentially replicating unquestioningly the rhetoric of two particular nation states. Saudi Arabia and Iran are perhaps the two most significant powers in the Middle-East, and since the Iranian Revolution in the 1970s, both have been vying for ascendency. Saudi Arabia especially has been exporting anti-Shia theology in a bid to delegitimise Iran and isolate it from other Muslim-majority nations.

Both nations recognise that amongst Muslims, any claim to legitimacy and authority to rule must be expressed in religious terms. Murtaza Hussain, a journalist at The Intercept, argues that Iran however, is less eager to push sectarian rhetoric than Saudi – ‘Iran’s statements are much more conciliatory because they know they can never achieve their goal of leading a largely Sunni Muslim world if they are openly sectarian’.

Conflict in the Middle-East is very much about resources and influence; it is of course however marked by religious rhetoric — rhetoric however that should rarely be taken at face value.

The Syrian Civil War

What about in nations such as Syria, where a Shia government is fighting against a Sunni populous? Surely here the claim of a Sunni-Shia conflict has merit?

Again the reality is more complicated. It was only in 1973 that modern Shias formally accepted Allawis (the religious sect to which the Assad family belong) as a branch of Shia-Islam. Musa al-Sadr, a senior Shia cleric in Lebanon, issued the fatwa, which brought centuries of ambiguity to an end. Until then — the Allawis were an unknown quantity. The religion was certainly influenced by Islam, but much else too, and Orthodox Sunnis and Shias both were sceptical of the high secretive tradition. Al-Sadr’s fatwa was as much motivated by politics as by piety — but it should underscore the fractured nature of religion and power in the Middle-East — a fracturing that is most clear in Syria today.

Journalists who consistently frame the conflict in sectarian terms also add to a pressure for religious groups to adhere to a particular political standpoint.

‘It’s called legitimacy by blackmail’ says James Gelvin, an academic and author who has researched the Middle East and Arab Spring. He explains to me the relevance of a Shia identity for Syria’s Assad Regime; ‘What the Syrian government has done is make itself stable by identifying the government with a particular sect, what they have done is forced other members of that sect into support of the government.’ It is a common tactic not only in Syria but in Bahrain also; ‘What that means of course is that the government tells minority communities, ‘if you do not support us, you’re dead, the majority will do something to you’’.

When journalists in the West repeat the ‘legitimacy by blackmail’ narrative in newspaper reports, they make the job of important bridge-builders, such as an Allawite Shia who doesn’t support the Assad regime, even more dangerous.

The same tatic is used by cheerleaders of the conflict, framing the Syrian Civil War as one between to Sunnis and Shias so as to garner theological support from certain quarters or to delegitimise claims of authority in other quarters. Muhammad Reza Tajiri, a Shia scholar in the United Kingdom, believes ‘the Syrian conflict certainly did not start on sectarian grounds, but as a result of opportunism from ‘scholars’ of both sides, the sectarian ideological issue is now inseparable from the conflict’.

Misleading Analysis

But it is clear that sectarianism is an element of the conflict; a devil’s advocate may argue that describing the conflict as Sunni-versus-Shia isn’t inaccurate. To truly appreciate how misleading it can be, try the following thought experiment.

Imagine a newspaper in the Middle-East, let’s say reporting in the 1990s. It is covering The Troubles of the UK and Ireland, specifically the Manchester Bombing of 1996. The headline of this piece is ‘The vicious schism between Protestant and Catholic has been poisoning Christianity for 500 years – and it’s getting worse’.

You begin reading the first few paragraphs of this article which professes to trace the history of the conflict between Britain and Ireland. It then locates the source of this conflict as beginning with Martin Luther nailing the Ninety-Five Theses to the door of Castle Church in Wittenburg.

The article concludes that the only way to resolve the dispute over Northern Ireland is sitting the Archbishop of Canterbury down with the Archbishop of Westminster to hammer out points of theological divergence, perhaps beginning with Transubstantiation. Only then, the author argues, can we hope for peace in Western Europe.

This bizarre article would never address the core of the issue, nor the problems being faced, nor offer any real solutions or clear ways forward. In fact, by choosing and forcing the narrative of a Christian sectarian conflict, it obfuscates the issue so drastically that it is useless.

It is the same with the Middle-East. Sectarianism is an aspect of Syria, but should the Muslim world come to some consensus about who should have been leader after the Prophet Muhammad, the difference at the centre of the original Sunni-Shia divide, the conflict in Syria would not cease.

Despite this, it isn’t uncommon to find articles talking about Syria, Bahrain or Pakistan, beginning with a discussion about 7th century Islam and disputes of who should be the next leader, Abu Bakr or Ali. Clearly this is neither insightful nor informed.

Alternative Understandings

If sectarianism is the wrong paradigm by which to understand conflicts in the Middle-East? How should they be understood?

‘The region has been economically stagnant’ believes James Gelvin, who has written extensively on the economic and social factors that led to the Arab Spring; ‘there is a largely young demographic, an unemployed youth, living amongst regimes that are incredibly oppressive’. Murtaza Hussain agrees that the problem is a combination of ‘economic failure’ and ‘identity politics’.

There is an emphasis sometimes put on the Saudi Arabia-versus-Iran cold war, but there are other pressures too. Most recently, the fracturing of relationships highlights how Qatar has emerged as a major player in the region. Saudi Arabia and Qatar have increasingly been hyping up tensions and rhetoric (a very Sunni-versus-Sunni conflict, to use the sectarian lens). Turkey too has very carefully developed links with post-Arab-Spring states, positioning itself as a potential moral voice for Muslims globally. The United States, which supports the Egyptian army with $3 billion annually, and Russia, which is propping up a beleaguered Assad Regime in Syria, also have deep interests in the region.

Conflicts are messy. Tony Blair’s speech in late April showed this most clearly. He advocated supporting intervention in Syria, but creating ties with Russia to fight Islamist threats. Yet Russia is supporting Assad, the same regime fighting the rebels Blair suggests offering support. His policy would quite literally force Britain and other Western nations to support two sides of the same war.

If experienced statesman like Blair can’t provide a coherent narrative without stumbling over themselves, we should certainly be wary of newspapers that simplify the problems of the Middle-East using the Sunni-versus-Shia schism.

Perhaps best to conclude then with James Gelvin:-

“In terms of the Middle East, the straw people always grasp at first is religion. They don’t do that in the case of the West. If there is a problem, it’s not a national problem, it’s not an economic problem, it has to be nailed on religion. It’s facile, simplistic and lazy analysis.”

References

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso Books.

Axworthy, M. (2017, August 25). Islam’s great schism. New Statesman, 146(5381), 22–27. https://www.newstatesman.com/world/middle-east/2017/08/sunni-vs-shia-roots-islam-s-civil-war

Haddad, F. (2014). Secterian relations and sunni identity on post-civil war Iraq. In L. G. Potter (Ed.), Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf (pp. 67–115). Oxford University Press.

Harney, J. (2016, January 4). How Do Sunni and Shia Islam Differ?, Correction notice. The New York times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/04/world/middleeast/q-and-a-how-do-sunni-and-shia-islam-differ.html

Louër, L. (2014). The State and Sectarian Identities in the Persian Gulf Monarchies: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait in Comparative Perspective. In L. G. Potter (Ed.), Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf (pp. 117–143). Oxford University Press.

Jones, J. (2016). Sectarian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the Arab Spring That Wasn’t [Book Review] Journal of Islamic studies, 27(2), 242–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/jis/etv108

Matthiesen, T. (2013). Sectarian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Spring That Wasn’t. Stanford University Press.

Potter, L. G. (Ed.) (2014). Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf. Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. D. (2000). The Nation in History: Historiographical Debates about Ethnicity and Nationalism. University Press of New England.