It is a truism to say that American dependence on oil has long influenced US foreign policy especially from the post–WWII era of geopolitical competition, through post Cold War era deregulation, to today with fist-bumping and bemoaning the Saudis to pump more and more oil until the cost of living for the working classes of the west eases (economically speaking it is counterintuitive for the seller, likely to result in unintended consequences if the oil-rich Gulf were to kowtow, and be disastrous for the Paris Accords). But there’s an argument to be made that “energy security” for the buyers will likely lead to “political instability” for the sellers.

Oil Blessings & The U.S. Dollar

📕 “Maps, aesthetically scientific” →

📕 “Oil’s corruptive capacity” →

As Mundy (2020) writes in “The Oil for Security Myth and Middle East Insecurity” (for MERIP, the Middle East Research and Information Project) since the 1970s, the Middle East has been the location of a third of all recorded wars between states, nearly 40 per cent of all internationalised civil wars and seven out of ten wars of occupation. With the launching of America’s global war on terrorism, a third of all new armed conflicts have emerged in the Middle East since 2000; that number has grown to half since 2010. The Middle East’s share of all terrorism related events worldwide, as defined by the Global Terrorism Database, has likewise increased from 10 percent in the 1970s to over half since 2010.

As Mead (2019) wrote in a review of “Lords of the Desert: The Battle Between the United States and Great Britain for Supremacy in the Modern Middle East” (Barr, 2018), the British Labour government that took power in the summer of 1945 soon concluded that keeping as much of the Middle East’s oil as possible under British rule—and thus within the sterling zone—offered the best, perhaps the only, hope of maintaining the United Kingdom’s place in the first rank of world powers. This conviction became the lodestar of post war British policy. At first, the prospects looked good. Pro-British monarchs ruled in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, and the Gulf kingdoms. There were, however, two problems with the plan: Arab nationalists wanted no part of British rule, and the United States was willing and able to displace the United Kingdom as the dominant regional power.

“Shadow Wars,” reviewed

Steve Donoghue

2016. The Christian Science Monitor

Anyone who’s seen the videos — and everyone has seen the videos — will have the same set of questions. The videos show schoolgirls being herded out of their classrooms by armed men who shout their organization name loudly and clearly for the video cameras. They show markets and nightclubs with flashing police sirens outside, forlorn groups of bystanders standing around hoping for news of loved ones inside. They show priceless ancient ruins being dynamited. They show journalists kneeling in the desert, squinting in the sunlight moments before they’re beheaded.

They show a naked, strident barbarism that seems like it belongs in a different age. The names are as familiar as the videos: al-Qaeda, the Taliban, Boko Haram, ISIS. And the questions that arise inevitably are always the same: Who are these people? Where did they come from? What do they want?

Christopher Davidson is a reader in Middle Eastern Politics at Durham University, author of the landmark study “After the Sheikhs,” and his big new book, “Shadow Wars: The Secret Struggle for the Middle East” comes closer than any recent popular study to offering definitive answers to those and other questions.

The patterns were set during the great imperial heyday of Continental gamesmanship, when British satraps all throughout the Middle East often propped up the most fiercely conservative Islamic fundamentalists because they made more effective regional buffers against the forces of Russian encroachment.

And the further along Davidson’s book progresses, the more those patterns come to look unbreakable. The Western powers intervene, meddle, support, subsidize, and double cross, constantly using the rhetoric of good stewardship while caring only about securing oil and land bases to parry the ambitions of the other regional chess masters, primarily the Russians. In all cases, long-term strategies are forgotten in the cloak-and-dagger mania of short-term tactics, and the result is a word that crops up all throughout Davidson’s book: blowback – unintended consequences that are intensely predictable in hindsight.

So an American Secretary of State can on a Monday deliver a stirring address about the sanctity of human rights in “the developing world” and on a Tuesday declare that the local dictator is a close personal friend of the family and must remain in power to ensure the stability of the region. So the United States can funnel covert funding and training to jihadist guerrilla forces in Afghanistan in the 1980s in order to use them as catspaws against the Soviets, without sparing much concern for the fact that the jihadis in question hated America as fervently as they hated the Russians – without, in other words, even trying to envision blowback that might involve one of those jihadi guerrilla fighters, Osama bin Laden, going on to strike at his American benefactors. Even when the warning signs are tragically explicit, they often go unheeded, as Davidson chronicles in theaters of operation stretching from West Africa to Central Asia.

The pattern holds firm everywhere from Syria to Qatar to Yemen to Libya to Somalia to Nigeria: Great Britain or France or the United States will pick some “partner” in a volatile region like Iraq, bet all the markers on that partner being a willing agent of democratic reform even though that partner is very visibly a power-bloated monster, and then, years down the line, express pious horror when that partner turns out to be a power-bloated monster.

In the mass of historical and geopolitical information Davidson assembles in these pages, some notes sound again and again. One of these of course is the so-called “Arab Spring” of 2011, in which enormous and almost entirely peaceful popular protests swept through the Arab world. Since the movement posed a direct threat to the status quo, it predictably received tepid response from those holding power in the region – most certainly including the United States.

Another of these recurring notes is something of longer-standing centrality to American foreign policy: Saudi Arabia, staunch ally, trade partner, and arms market to the United States, turns up repeatedly playing a game of its own, harboring, sponsoring, and financing Islamic terrorists in their operations against the United States. Running through virtually every tale of Middle Eastern violence and treachery Davidson relates is at least some strand of Saudi complicity; American policymakers might be familiar with this most dangerous of double standards, but it’s a good bet the general American public – which in poll after poll seems unaware of the fact that 15 of the 19 al-Qaeda terrorists who attacked America on September 11 were Saudi nationals – would be alarmed by it. For its unsparing probity, Davidson’s book ought to be required reading with both groups.

And what about the answers to those fundamental questions – Who are these people? Where did they come from? What do they want? “Shadow Wars” makes the answers painfully, damningly clear. What the book doesn’t do is offer any way out of the old patterns it describes, since arbitrary withdrawal causes just as much blowback as arbitrary involvement. But if some future solution is discovered, it’ll be thanks to the path-clearing of books like this one.

Shadow Wars: Reviews

Hilal Khashan

2017. American University of Beirut

Davidson of Durham University seeks to answer the question: Why has the Arab quest for democracy been bogged down in a murky quagmire while “parts of Europe, Latin America, and even Africa once managed to cut the shackles of authoritarianism.” The answers he provides, however, implicating the United States and Britain in all Arab political problems, do not satisfy.

Individually, many of the examples Davidson provides make sense, for example, that the U.S. military establishment became concerned about reductions in spending after the drawdown of U.S. troops from Western Europe. It is difficult, however, to accept that the need “to protect U.S. defence spending” was the primary reason for President George H.W. Bush’s decision to go to war against Iraq in 1991. This reductionist analysis suggests sensationalism.

The author dwells at length on the mischievous role of the West in the region’s “deep state” counterrevolutions, which aborted the “Arab Spring.” There is no denying that the foreign policy of Washington and its Western allies is muddled at best, but to assign to them such overpowering influence relieves Arab dictators from their own responsibility and failure. Similarly, he asserts that Washington had a role in the creation of the Islamic State (ISIS) and criticizes the Obama administration’s lack of resolve to destroy it. But he insults the reader’s intelligence when he claims that the many accounts of ISIS barbarity “were poorly sourced, and some were definitely made up.”

The book would have benefited from more editing and factual review (Egyptian president Anwar Sadat expelled all Soviet advisors in 1972, not 1971) and, considering its voluminous size, should have an index. But most seriously, the book is too thin on analysis. Davidson grounds his book in a neoclassical counterrevolution theory whose building blocks are not particularly appropriate for studying the evolution of Arab societies during the past two centuries. The theoretical inadequacies of Shadow Wars weaken its arguments and impede convincing conclusions.

John Waterbury

2017. New York University, Abu Dhabi

According to Davidson, for more than a century, the intelligence and military establishments of the United Kingdom and the United States have been leading a hidden struggle against implicitly progressive forces in the Middle East, driven by a desire for geopolitical advantage and the control of oil. Notwithstanding the declaration of a “war on terror;’ Davidson believes that the preferred instruments of the Americans and the British have been Islamist movements: the Muslim Brotherhood, the Taliban, and, most recently, the Islamic State (also known as ISIS). The Americans and the British have often found themselves fighting their own proxies, but they knew that would happen, Davidson claims. They therefore fight halfheartedly, he contends, so that such groups continue to survive. Nearly all of Davidson’s sources are in the public domain: he uncovers no original evidence for his argument and instead assembles familiar pieces into an unfamiliar shape. The results are unconvincing. For example, if Western powers fostered ISIS in order to drive a Sunni wedge between Iran and Syria, why did they bother to topple Saddam Hussein, who already played that role? More troubling, Davidson’s analysis denies agency to Islamists, Middle Easterners, and pretty much everyone else: in his view, we are all merely pawns in the shadow wars.

Douglas Little

2017. Clark University, Massachusetts

The meteoric rise in 2014 of the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) has spawned a dizzying array of articles and books seeking to place this latest Middle East horror show into historical perspective. Among the most ambitious, provocative, and tendentious is Shadow Wars by Christopher Davidson, a lecturer in Middle East politics at the University of Durham. Davidson at-tributes the emergence of ISIS and other extremist groups to “the long-running policies of successive imperial and ‘advanced capitalist’ administrations” in Britain and America and “their ongoing manipulations of an elaborate network of powerful national and transnational actors across both the Arab and Islamic worlds” (pp. viii–ix). Shadow Wars synthesizes the writings of William Blum, Robert Dreyfuss, Mark Curtis, and like-minded critics of British and American policies to create what might be called a unified field theory of Western imperialism in the Middle East, suggesting along the way that many recent grisly terrorist actions in Iraq and Syria may actually have been “false flag” operations designed to legitimate military intervention by the United Kingdom and the United States. After I finished reading this information-packed, but often eye-glazing 700-page monograph, I said to myself: If Naomi Klein and Robert Ludlum had decided to coauthor an account of recent events in the Middle East, they would have produced something like Shadow Wars.

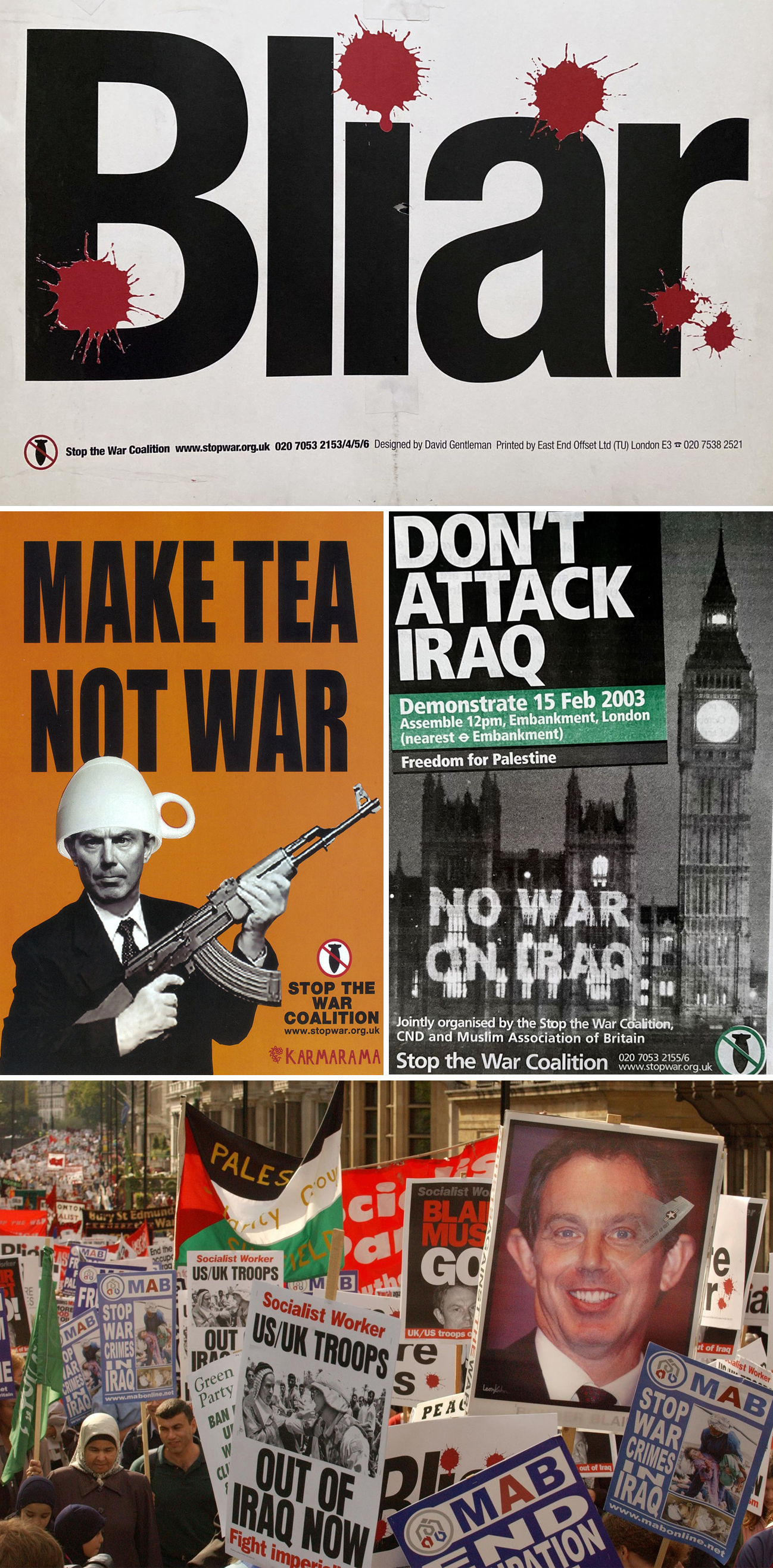

Although Davidson has made good use of the WikiLeaks “Cablegate” database of leaked US diplomatic documents along with some on-the-ground interviews, he relies mainly on secondary sources rather than archival materials to tell his story. Frequently, he veers off into the acronym-laden political underbrush, where Islamic splinter groups de-bate how many infidels can dance on the head of a pin. Once one clears away Davidson’s forest of thick description, his master narrative looks something like this. After 1945, British and American officials, frequently working in concert, cultivated ties with Islamic groups, first to counteract Arab and Iranian nationalists who threatened Western control of Middle East oil during the 1950s and 1960s and later to defeat Soviet forces in Afghanistan during the 1980s. So far this is a familiar story already well-told by scholars like Joel Gordon, Mark Gasiorowski, and Steve Coll, but Davidson presses beyond the end of the Cold War to argue that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s intervention in the Balkans during the 1990s was not intend-ed merely to defend a motley crew of Bosnian and Kosovar Muslims but also to serve as a dress rehearsal for military intervention in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya early in the 21st century. After the attacks on September 11, 2001, US president George W. Bush and UK prime minister Tony Blair, with help from pro-Western Muslim autocrats in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf shaykhdoms, launched a global crusade against terrorism designed to undermine Islamic reformers, reinforce the neoliberal Washington Consensus, and rev up the military-industrial complex on both sides of the Atlantic via massive amounts of defence spending and arms sales.

While Davidson’s interpretation of the War on Terror reads like a chapter from Vladimir Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, his explanation of the causes and consequences of the Arab Spring is bewildering. Spontaneous grassroots revolts against pro-Western kleptocracies in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen and anti-Western autocracies in Libya and Syria were discredited and eventually crushed by an unholy alliance of military officers in Cairo and oil shaykhs in Riyadh and Doha with the blessing of the administrations of Barack Obama and British prime minister David Cameron, who paid little more than lip service to democracy and human rights. Indeed, in the case or Libya, Davidson implies that Washington and London conspired to bring down Mu‘ammar al-Qadhafi through “a fake Arab Spring” in order reopen the richest oil fields in North Africa to multinational corporations based in the US and UK.

Davidson’s analysis of the emergence of ISIS is downright bizarre. In a chapter entitled “The Islamic State: A Strategic Asset,” he asks, “qui bono?” (who benefits?). The answer, of course, is American and British corporate interests and their allies in Saudi Arabia, all of whom agree that “the rise of the Islamic State has been spectacularly good for business” (p. 406). Furthermore, according to Davidson:

“Although the new caliphate’s savagery may seem unconscionably nihilistic, it nonetheless serves an equally important purpose for those on the outside, as even after the Arab Spring the surviving Western-backed autocracies have been able to confirm their status as the Middle East’s “moderates,” just as they were during the War on Terror and, before that, against the threat of international communism.”

— 405–406

Later in this chapter, Davidson claims that the Obama Administration intentionally ignored warnings about ISIS until mid-2014 in the hopes to drive a Sunni wedge into the “Shi‘i crescent” that stretches from Damascus to Tehran. One of his chief sources for this is Michael Flynn — Barack Obama’s onetime director of the Defence Intelligence Agency and, more recently, Donald Trump’s short-lived National Security Advisor — who told Al Jazeera in 2015 that “there was a decision in the US government knowingly to support such extremist groups” (quoted on p. 421). As for Obama’s drone strikes and covert operations against ISIS, Davidson regards them merely as proof that the United States was “trying to find the right balance between being seen to take action but yet still allowing the Islamic State to prosper” (p. 422).

This is not the only time in Shadow Wars where Davidson suggests that there is a dark conspiracy at work in the Muslim world. He claims that Western intelligence agencies exaggerated reports that Serbian paramilitary units killed 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in the “Srebrenica massacre” (the quotation marks are Davidson’s) in order “to provide a casus belli” for NATO intervention in 1995 (p. 135). Davidson notes without editorial comment that “Libyan bloggers” identified the man lynched in a ditch outside Sirte in October 2011 as prob-ably “one of Gaddafi’s many very realistic body doubles” (p. 297). Davidson implies that the sarin gas attacks on Syrian rebels at Ghuta two years later were carried out not by the regime of Bashar al-Asad but by the rebels themselves (p. 330). Most controversial of all, Davidson suggests that there is evidence of “camera trickery” and other video “inconsistencies” (pp. 425, 500) in two of the most gruesome acts committed by ISIS, the beheading of James Foley and the burning alive of Royal Jordanian Air Force pilot Mu’adh al-Kasasiba, adding for good measure that some “experts” believe that pictures of the graphic murder of a Japanese hostage were enhanced by a set of “Photoshopped images” (p. 503).

What then are we to make of Christopher Davidson’s unified field theory seeking to explain a century of war, revolution, and terrorism in the Middle East? He presents solid evidence that the Western powers did employ Islam as an antidote to radical Arab nationalism during the Cold War. He reminds us that although US and UK policy-makers have always insisted that their interventions in the Muslim world were never about oil, crises like the Suez War in 1956 and Operation Desert Storm in 1991 were almost entirely about oil. And he reveals the hypocrisy of American and British leaders, who have talked the talk of democracy from the age of Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq in Iran (1951–53) through the era of Mohamed Morsi in Egypt (2012–13) while refusing to walk the walk. Today, ‘Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi in Cairo is indeed the second coming of Mohammad Reza Shah in Tehran 65 years ago.

Yet Davidson’s explanation of more recent developments, frequently couched in adverbs like “worryingly” and “intriguingly” and “sinisterly,” seems off the mark. Despite Davidson’s insistence that ISIS is little more than a band of “useful idiots” and social media addicts serving the interests of malevolent Persian Gulf royals and multinational corporations, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his extremist followers are in reality accidental opportunists who have taken advantage of America’s greatest geopolitical blunder in one hundred years to unleash a reign of terror. Far from being a valuable “strategic asset” for the Western powers and their clients in the Middle East, ISIS is a grave strategic threat whose reliance on 21st century social media and 7th century barbarism promises to keep Donald Trump, Prime Minister Theresa May, and their successors awake at night for many years to come.

The plot thickens

Iraq (et al.)

Two books, together, tell a compelling tale,

In the first, Rutledge (2005) traces the origins of America’s addiction throughout the twentieth century and explains how America’s relations with the Middle East were developed through its quest for energy security. America’s motorisation and its consequent demand for oil at predictable market prices was and continues to be an important influence on US policy towards Iraq – especially given the uncertainties relating to what has so far been the securest source of Middle East oil – Saudi Arabia. Ian Rutledge argues that the war in Iraq was neither a war for ‘freedom’ or ‘democracy’ nor was it a plot to ‘steal Iraq’s oil’, but rather an attempt to establish a pliant and dependable oil protectorate in the Middle East which would underwrite the soaring demand from America’s hyper-motorised consumers. In this work, Rutledge undertakes an in-depth analysis of the motorisation of US society and explicitly links this to America’s foreign policy adventures, past and present.

In the second (Rutledge, 2014) In 1920 an Arab revolt came perilously close to inflicting a shattering defeat upon the British Empire’s forces occupying Iraq after the Great War. A huge peasant army besieged British garrisons and bombarded them with captured artillery. British columns and armoured trains were ambushed and destroyed, and gunboats were captured or sunk. Britain’s quest for oil was one of the principal reasons for its continuing occupation of Iraq. However, with around 131,000 Arabs in arms at the height of the conflict, the British were very nearly driven out. Only a massive infusion of Indian troops prevented a humiliating rout.

“Enemy on the Euphrates” is the definitive account of the most serious armed uprising against British rule in the twentieth century. Bringing central players such as Winston Churchill, T. E. Lawrence and Gertrude Bell vividly to life, Ian Rutledge’s masterful account is a powerful reminder of how Britain’s imperial objectives sowed the seeds of Iraq’s tragic history.

“Iran–Iraq War” (1980–1988)

As Liu (2018) has said, there is no simple explanation for America’s conflicting actions, and the superpower played an integral though contradictory part throughout the Iran–Iraq War. Its actions ultimately benefitted neither Iran nor Iraq, but rather “the U.S. itself and its material interests in the Middle East.” Ultimately, American involvement, Liu continues, “exacerbated the already bloody conflict … and further contributed to lasting political insecurity in the region.”

“Gulf War” (1990–1991)

“Desert Storm”

1. The military buildup from August 1990 to January 1991; 2. The aerial bombing campaign against Iraq from the 17th January, 1991 onwards.

“Iraq War” (2003–2015)

References

Barr, J. (2012). A Line in the Sand: The Anglo-French Struggle for the Middle East, 1914–1948. W. W. Norton.

Barr, J. (2018). Lords of the Desert: Britain’s Struggle with America to Dominate the Middle East. Simon & Schuster.

Coll, S. (2004). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin Publishing Group

Coll, S. (2024). The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the CIA, and the Origins of America’s Invasion of Iraq. Penguin Publishing Group.

Curtis, M. (2003). Web of Deceit: Britain’s Real Role in the World. Vintage.

Curtis, M. (2004). Britain’s Real Foreign Policy and the Failure of British Academia. International Relations, 18(3), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117804045193

Davidson, C. (2016). Shadow Wars: The Secret Struggle for the Middle East. Oneworld Publications.

Donoghue, S. (2016, November 17). ‘Shadow Wars’ exposes underlying patterns behind Middle Eastern strife, Book review. The Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/Books/Book-Reviews/2016/1117/Shadow-Wars-exposes-underlying-patterns-behind-Middle-Eastern-strife

Gasiorowski, M. J., & Byrne, M. (Eds.). (2004). Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran. Syracuse University Press.

Gordon, J. (1992). Nasser’s Blessed Movement: Egypt’s Free Officers and the July Revolution. Oxford University Press.

Khashan, H. (2017). Shadow Wars: The Secret Struggle for the Middle East. Middle East Quarterly, 24(2). https://www.meforum.org/middle-east-quarterly/book-reviews/shadow-wars-the-secret-struggle-for-the-middle

Little, D. (2017). Shadow Wars: The Secret Struggle for the Middle East. The Middle East Journal, 71(2), 328–330. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90016332

Liu, B. (2018, December 3). U.S. Involvement in the 1980s Iran-Iraq War: America’s Haphazard Extension of Gulf Insecurity. The Yale Review of International Studies. https://yris.yira.org/column/u-s-involvement-in-the-1980s-iran-iraq-war-americas-haphazard-extension-of-gulf-insecurity/

Mead, W. R. (2019). Lords of the Desert: The Battle Between the United States and Great Britain for Supremacy in the Modern Middle East. Foreign Affairs, 98(1) 201–201. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26798040

Rutledge, I. (2005). Addicted to Oil: America’s Relentless Drive for Energy Security. I.B. Tauris.

Rutledge, I. (2014). Enemy on the Euphrates: The British Occupation of Iraq and the Great Arab Revolt, 1914-1921. Saqi Books.

Waterbury, J. (2017). Shadow Wars: The Secret Struggle for the Middle East. Foreign Affairs, 96(1), 185–185. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2017-02-13/shadow-wars-secret-struggle-middle-east