As Kamrava (2012) wrote, across the Arabian Gulf “an authoritarian retrenchment and narrowing of political space has emerged.” This reassertion of the state’s dictatorial authority has, of course, taken different forms across the region depending on the state’s overall societal posture. In Qatar, for example, where anti-state sentiments are conspicuous in their absence, there have not been any discernible changes in the domestic political environment. In the UAE, however, the space provided to civil society organisations has been steadily narrowed by the state since the beginning of the regional unrest. In Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, repression was notably more draconian still.

Abouzzohour (2021) ponders what are the implications of the fact that no monarch was overthrown during or since the Arab Spring. Various experts have linked the latter to monarchs’ legitimacy, external support, and resource wealth. She suggests that while there is no consensus view, “it is clear that monarchs have repeatedly and successfully contained different types of opposition threats for decades prior to the Arab Spring and continue to do so 10 years later.”

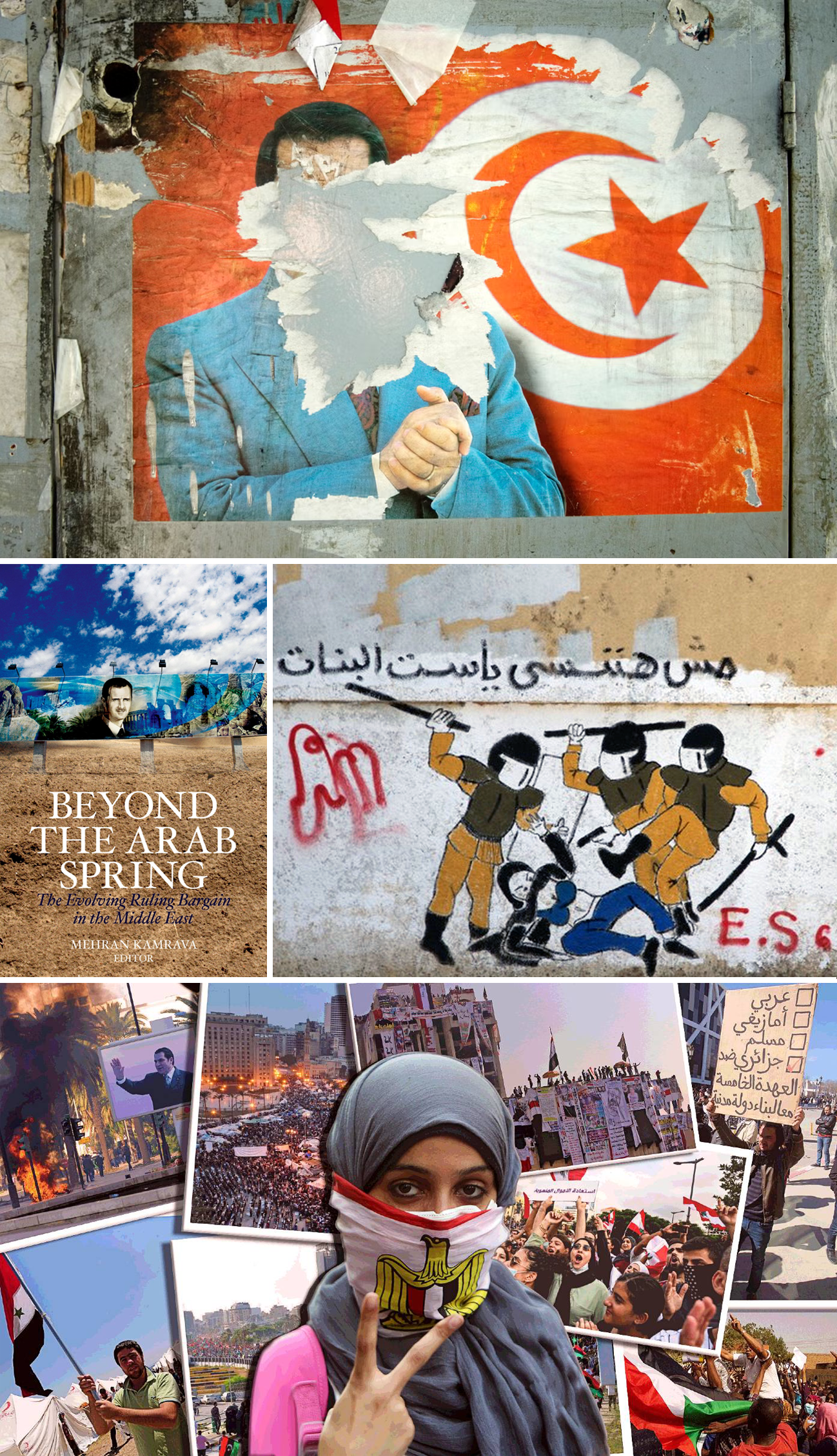

Ten years on from the “Arab Spring” The Economist (2020) write:

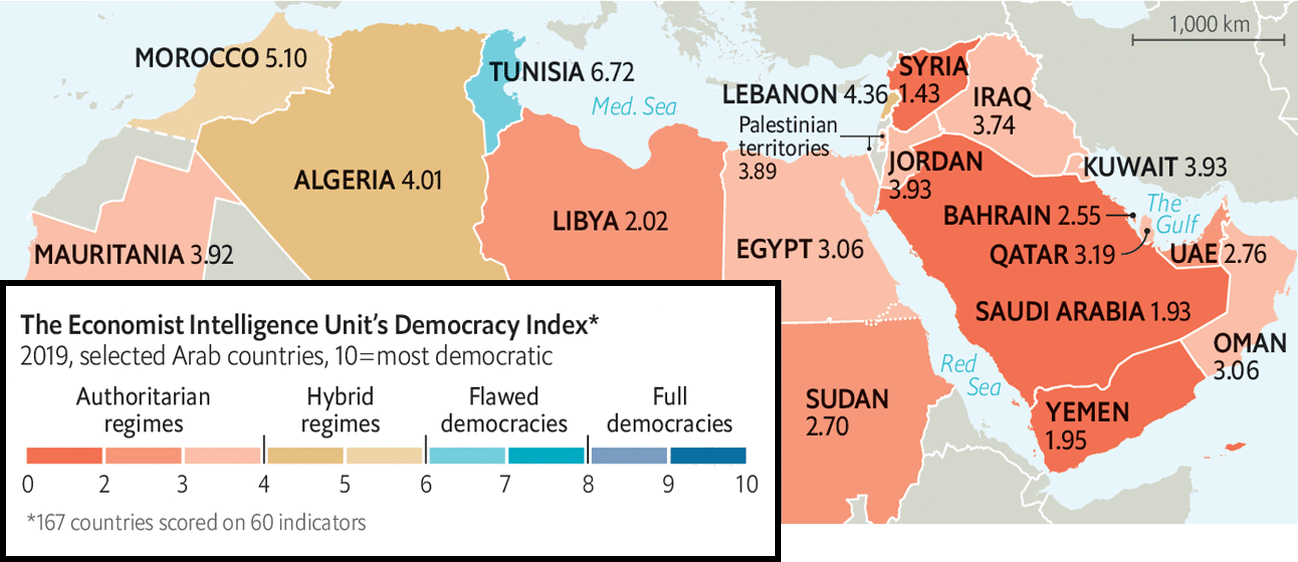

“What kind of repression do you imagine it takes for a young man to do this?” So asked Leila Bouazizi after her brother, Muhammad, set himself on fire ten years ago. Local officials in Tunisia had confiscated his fruit cart, ostensibly because he did not have a permit but really because they wanted to extort money from him. It was the final indignity for the young man. “How do you expect me to make a living?” he shouted before dousing himself with petrol in front of the governor’s office. His actions would resonate across the region, where millions of others had reached breaking-point, too. Their rage against oppressive leaders and corrupt states came bursting forth as the Arab spring. Uprisings toppled the dictators of four countries—Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen. For a moment it seemed as if democracy had arrived in the Arab world at last. … Only one of those democratic experiments yielded a durable result—fittingly, in Bouazizi’s Tunisia. Egypt’s failed miserably, ending in a military coup. Libya, Yemen and, worst of all, Syria descended into bloody civil wars that drew in foreign powers. The Arab spring turned to bitter winter so quickly that many people now despair of the region. Much has changed there since, but not for the better. The Arab world’s despots are far from secure. With oil prices low, even petro-potentates can no longer afford to buy their subjects off with fat subsidies and cushy government jobs. Many leaders have grown more paranoid and oppressive. Muhammad bin Salman of Saudi Arabia locks up his own relatives. Egypt’s Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi has stifled the press and crushed civil society. One lesson autocrats learned from the Arab spring is that any flicker of dissent must be snuffed out fast, lest it spread.

The London-based magazine concludes that, “The region is less free than it was in 2010—and perhaps [now even] more angry.”

References

Abouzzohour, Y. (2021, March 8). Heavy lies the crown: The survival of Arab monarchies, 10 years after the Arab Spring. Brookings Doha. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/heavy-lies-the-crown-the-survival-of-arab-monarchies-10-years-after-the-arab-spring/

Colombo, S. (2012). The GCC and the Arab Spring: A Tale of Double Standards. The International Spectator, 47(4), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2012.733199

Kamrava, M. (2012). The Arab Spring and the Saudi-Led Counterrevolution. Orbis, 56(1), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2011.10.011

The Economist. (2020, December 19). Ten years after the spring. The Economist, 437(9225), 20-21. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/12/18/the-arab-spring-ten-years-on