Aesthetically Scientific

Map: Oil fields

Map: U.S. military bases

Oil’s ‘blessings’ & the American dollar standard

📕 “Political maps of Arabia” →

Map: Middle Eastern oil, 1945

Map: Middle Eastern oil, 1955

Map: Confessional patterns

* Includes gnostic Alawites & Alevis. ** Dated; see “Table: Religions in 2023 (%)” (below). Expand map. © Dr Michael Izady

* Includes gnostic Alawites & Alevis. ** Dated; see “Table: Religions in 2023 (%)” (below). Expand map. © Dr Michael Izady

Map: The Arabian peninsula, 1965

The World Atlas (1965). Expand map.

The World Atlas (1965). Expand map.

Map: The Arabian peninsula, 1965

The Arabian peninsula (1967). Expand map.

The Arabian peninsula (1967). Expand map.

Map: The Arabian peninsula, 1969

The Arabian peninsula (1969). Expand map.

The Arabian peninsula (1969). Expand map.

Map: The Arabian peninsula, 2016

The Arabian peninsula (DK, 2016). Expand map.

The Arabian peninsula (DK, 2016). Expand map.

Allocating oil-rent (“resource wealth” matters)

📕 “The Arabian Gulf Social Contract” →

📕 “Arabian Gulf sovereign wealth” →

Historical & Monumental

Empires, imperialism and Palestine… The following four pictures demonstrate just how political maps inherently are. One of them shows a map signed by Donald Trump with the word “nice” on a map of Israel indicating that the occupied Golan Heights belong to Israel, rather than Syrian territory. The Golan Heights were occupied by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War and then effectively annexed in 1981, a move that has not been recognised by the international community.

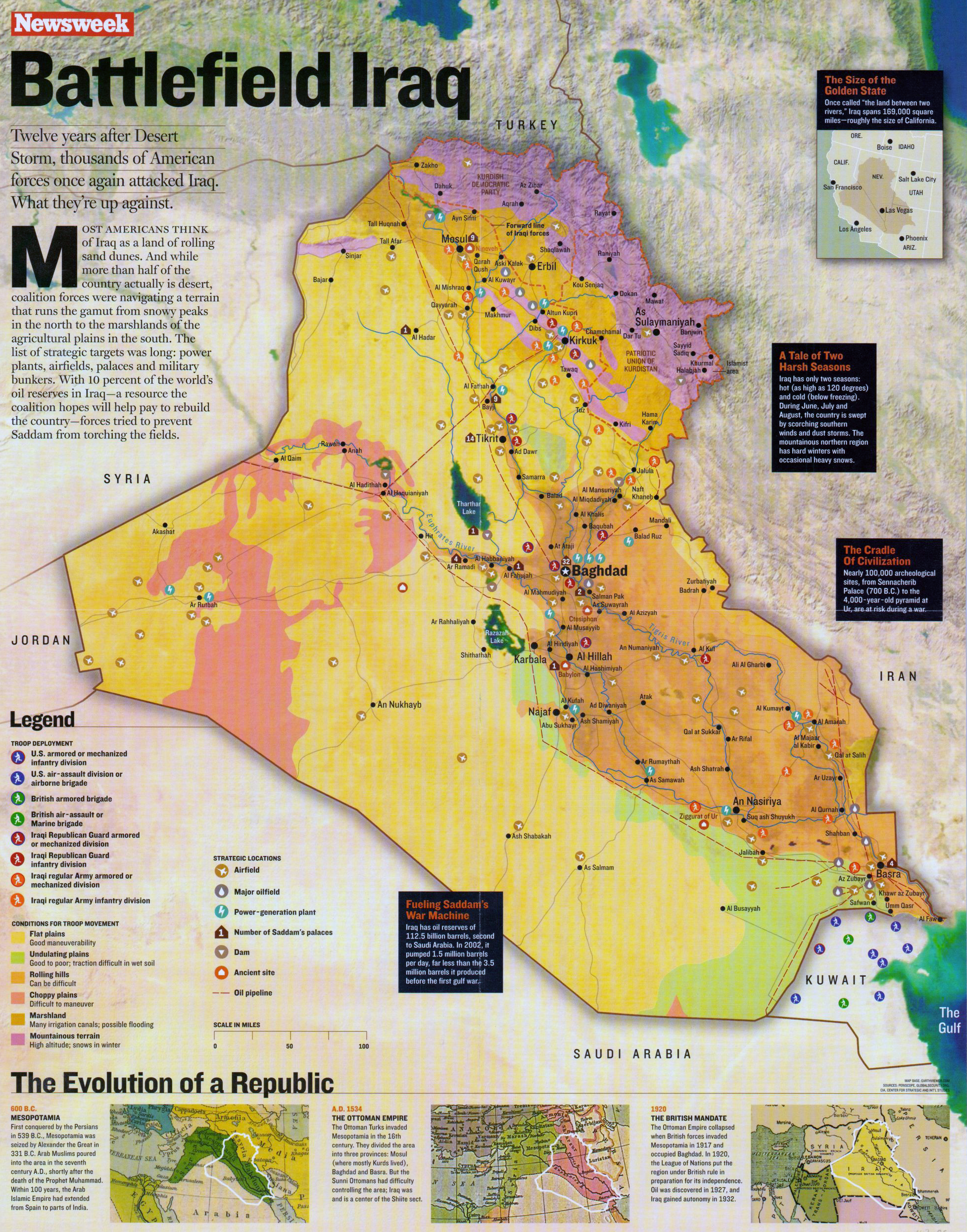

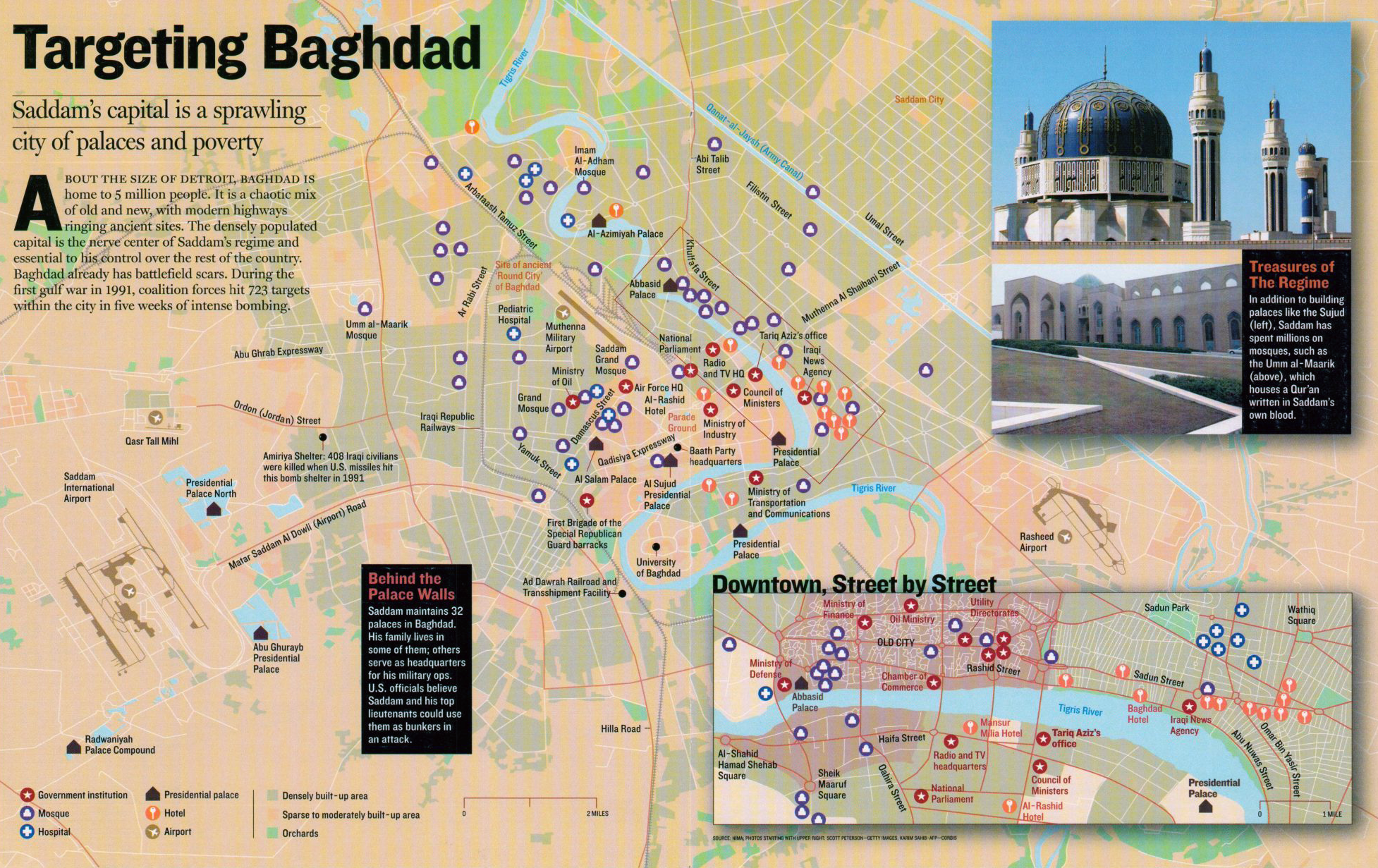

After the pictures, there are a series of empire-related maps. Then there are a number relating to the Iran and Iraq wars post-WWII and several more that chart/depict the fallout of the U.S. and the U.K.’s most recent war in Iraq: (1) “The Iran–Iraq War,” 1980–1988 (2), “The Gulf War,” 1990–1991 and (3), “The Iraq War,” 2003–2015. The latter maps are also in part resultant of the fallout of the “Arab Spring” but, what happened in Syria is very much linked to America’s actions in Iraq in the first decade of this current millennium.

Map: Palestine on the map

Map: Palestine; a disappearing act (?)

Map: Netanyahu and The Golan

Map: Netanyahu and vested interests

In an article for Al Jazeera — “Palestine to Africa: How maps lie — and some tell the truth” — Sarah Shamim (2024) tells the tale of Thameen Darby, a Palestinian from Jenin, who created the Nakba Layer, mapping Palestinian villages that were destroyed or depopulated in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. The maps showed parts of Palestine that are not even seen in maps created by Palestinian authorities, geographer Linda Quiquivix, who researched the Nakba map and maps of Palestine, told Sarah.

Map: The Persian Empire

Map: The Ottoman Empire

Map: English (et al.) imperialism

The Sykes–Picot Agreement was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from Russia and Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire. As per the Wikipedia page on the Sykes–Picot Agreement:

It was based on the premise that the Triple Entente would achieve success in defeating the Ottoman Empire during World War I and formed part of a series of secret agreements contemplating its partition. The primary negotiations leading to the agreement took place between 23rd of November 1915 and the 3rd of January 1916, on which date the British and French diplomats, Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, initialled an agreed memorandum. The agreement was ratified by their respective governments on 9th and 16th of May, 1916. The agreement effectively divided the Ottoman provinces outside the Arabian peninsula into areas of British and French control and influence. The British- and French-controlled countries were divided by the Sykes–Picot line. The agreement allocated to the UK control of what is today southern Israel and Palestine, Jordan and southern Iraq, and an additional small area that included the ports of Haifa and Acre to allow access to the Mediterranean. France was to control southeastern Turkey, the Kurdistan Region, Syria and Lebanon.

Occupied Gaza, Y2K

Map: “Iran–Iraq War” (1980–1988)

Iran–Iraq War, 1980–1988 — a war for oil fields? Expand map.

Iran–Iraq War, 1980–1988 — a war for oil fields? Expand map.

Map: “Gulf War” (1990–1991)

First/Second Gulf War — a war for the continued control of oil? Expand map.

First/Second Gulf War — a war for the continued control of oil? Expand map.

Map: “Iraq War” (2003–2015)

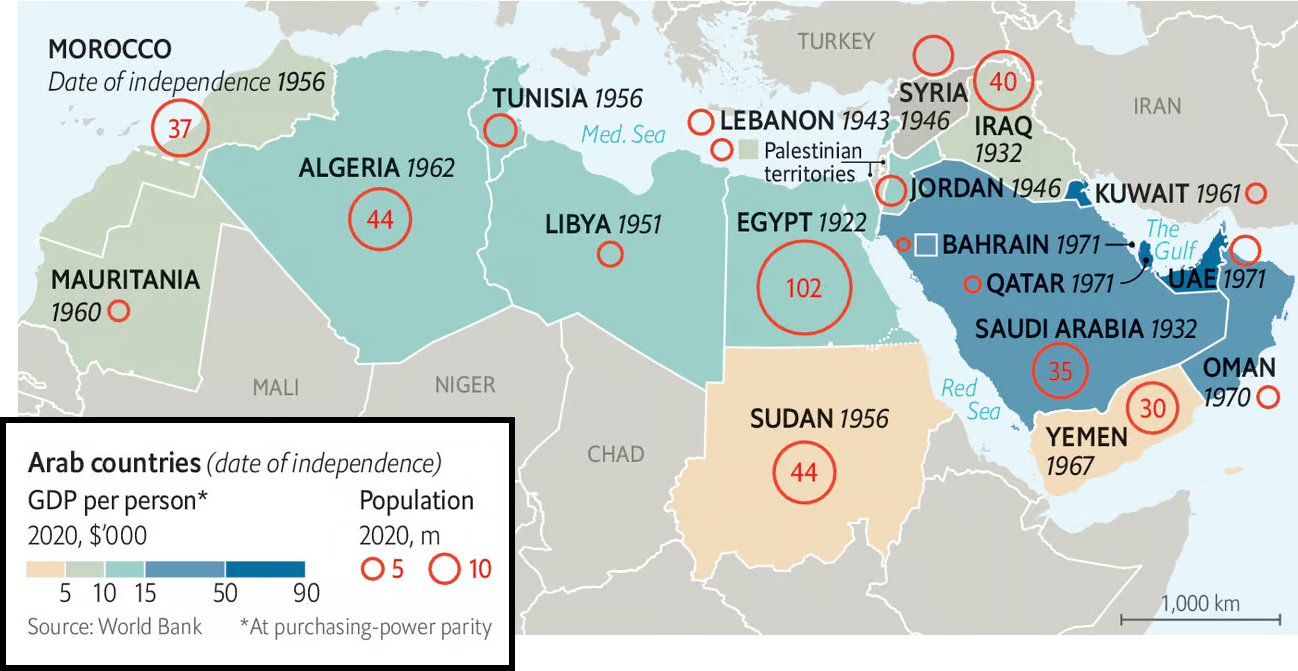

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

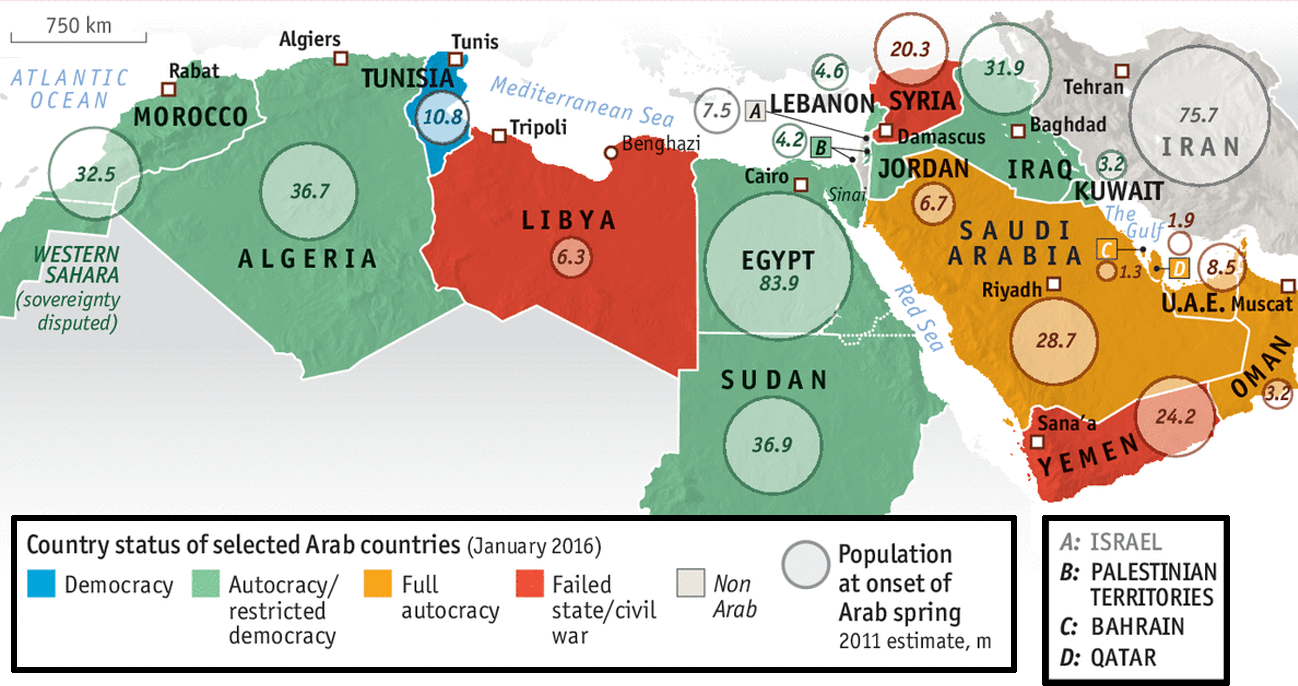

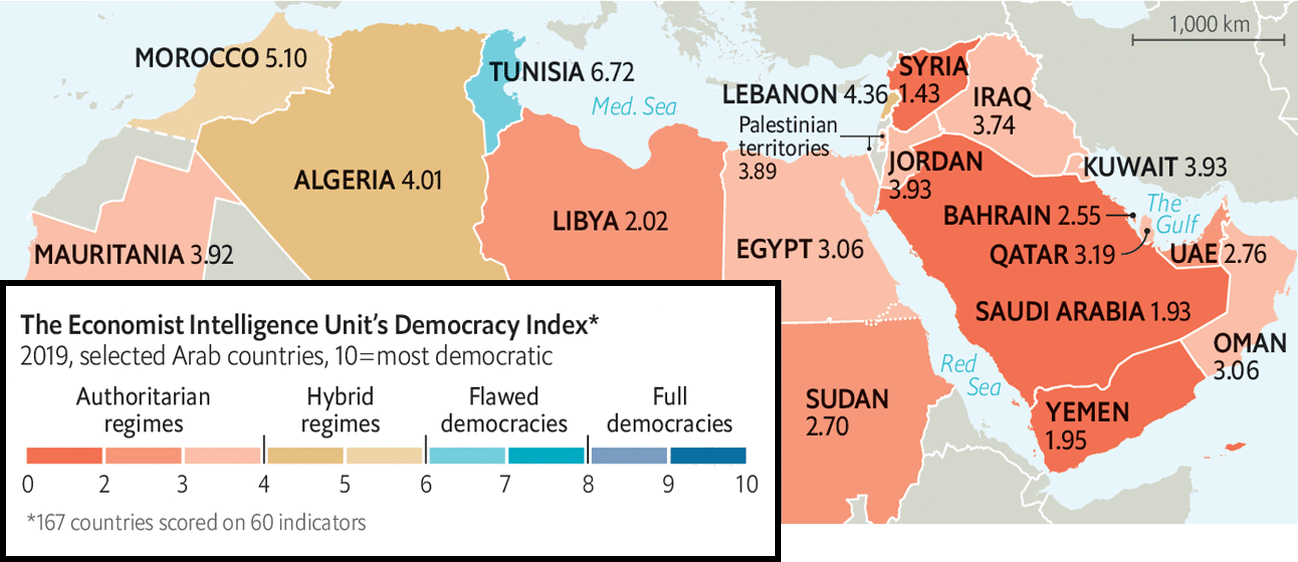

Ten years on from the “Arab Spring” The Economist (2020) write:

“What kind of repression do you imagine it takes for a young man to do this?” So asked Leila Bouazizi after her brother, Muhammad, set himself on fire ten years ago. Local officials in Tunisia had confiscated his fruit cart, ostensibly because he did not have a permit but really because they wanted to extort money from him. It was the final indignity for the young man. “How do you expect me to make a living?” he shouted before dousing himself with petrol in front of the governor’s office. His actions would resonate across the region, where millions of others had reached breaking-point, too. Their rage against oppressive leaders and corrupt states came bursting forth as the Arab spring. Uprisings toppled the dictators of four countries—Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen. For a moment it seemed as if democracy had arrived in the Arab world at last. … Only one of those democratic experiments yielded a durable result—fittingly, in Bouazizi’s Tunisia. Egypt’s failed miserably, ending in a military coup. Libya, Yemen and, worst of all, Syria descended into bloody civil wars that drew in foreign powers. The Arab spring turned to bitter winter so quickly that many people now despair of the region. Much has changed there since, but not for the better. The Arab world’s despots are far from secure. With oil prices low, even petro-potentates can no longer afford to buy their subjects off with fat subsidies and cushy government jobs. Many leaders have grown more paranoid and oppressive. Muhammad bin Salman of Saudi Arabia locks up his own relatives. Egypt’s Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi has stifled the press and crushed civil society. One lesson autocrats learned from the Arab spring is that any flicker of dissent must be snuffed out fast, lest it spread.

The London-based magazine concludes that, “The region is less free than it was in 2010—and perhaps [now even] more angry.”

Table: Religions in 2023 (%)

| Country | Sunni | Shia | Other |

| Bahrain a | 28 | 54 | 18 |

| Kuwait b | 66 | 17 | 17 |

| Oman c | 47 | 7 | 46 |

| Qatar d | 66 | 12 | 22 |

| Saudi Arabia e | 81 | 9 | 10 |

| The UAE f | 67 | 7 | 26 |

| Iran | 17 | 81 | 1 |

| Iraq | 35 | 61 | 4 |

| Jordan | 93 | 2 | 5 |

| Egypt | 90 | < 1 | 10 |

| Yemen | 44 | 55 | 1 |

As will become apparent when reading the notes to the above table, the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) relies heavily on the U.S. State Department’s annual International Religious Freedom Reports (that are submitted to the House of Congress annually in accordance with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998). Those said reports (linked to in the Table’s notes, below) paint a common theme: virtually all Gulf citizens are Muslim, but official demographics published by these countries do not delineate along confessional lines so, local media and think-tank reporting is relied upon.

a

The US state department’s 2023 IRF report on Bahrain estimates the total population to be approximately 1.5 million with Bahrainis numbering around 720,000 (June 2023 – compare with Arabian Gulf data). The Bahraini government does not publish statistics that delineate its the Shia and Sunni Muslim populations but, “estimates from NGOs and the Shia community state Shia Muslims represent a majority (55 to 70 per cent).”

b

The IRF Report on Kuwait The U.S. government estimates the total population at 3.2 million (midyear 2022). U.S. government figures also cite the Public Authority for Civil Information (PACI), a local government agency, which reports that the country’s total population was 4.8 million in 2023. As of June, PACI reported there were 1.5 million citizens and 3.3 million noncitizens. PACI estimates 74.7 percent of citizens and noncitizens are Muslims. The national census does not distinguish between Shia and Sunni Muslims. Nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and the media estimate approximately 70 percent of citizens are Sunni Muslims, while the remaining 30 percent are Shia Muslims (including Ahmadi and Ismaili Muslims, whom the government counts as Shia).

c

The IRF Report on Oman states that around 41 per cent of the Sultanate’s population constitutes foreign guest workers. Regarding the national Omani citizens, it is estimated that 45 per cent are Sunni, 45 per cent are Ibadi and most of the remainder are Shia (like its neighbours, the Omani government does not directly publish religious confession breakdowns). Note that the ARDA percentages in the Table above differ from those provided by the IRF.

d

According to the IRF Report on Qatar, as of 2023 Qataris made up approximately 11 per cent of the country’s total population and that “most citizens are Sunni, and almost all others are Shia.”

e

The IRF Report on Saudi Arabia estimates that around 85 per cent of Saudis are Sunni. The remainder are Shia, but in the oil-rich Eastern provinces of the country, this latter group comprises a substantial fraction (see: Oil’s corruptive capacity).

f

The 2023 IRF Report on the UAE suggests that approximately 11 per cent of the country’s population are Emiratis, of whom more than 85 per cent are Sunni. Most of the remainder, according to the report are are Shia citizens, “who are concentrated in the Emirates of Dubai and Sharjah.”

References

Filiu, J.-P. (2014). Gaza: A History. Oxford University Press.

Hourani, A. (1991). A History of the Arab Peoples. Faber & Faber.

Mackintosh-Smith, T. (2019). Arabs. Yale University Press.

McHugo, J. (2013). A Concise History of the Arabs. Saqi Books.

McHugo, J. (2017). A Concise History of Sunnis and Shias. Saqi Books.

Newsweek. (2003, March 31). Mapping the war: battlefield Iraq. Newsweek, 141(13).

The Economist. (2014, June 21). How did it come to this? The Economist, 411(8892), 45. https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2014/06/19/how-did-it-come-to-this

The Economist. (2016, January 11). The Arab spring, five years on. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2016/01/11/the-arab-spring-five-years-on

The Economist. (2020, December 19). Ten years after the spring. The Economist, 437(9225), 20-21. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/12/18/the-arab-spring-ten-years-on

The Economist. (2021, August 28). Why the Arab world has an identity crisis. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/special-report/2021/08/24/why-the-arab-world-has-an-identity-crisis

| i | This is the website of Dr Emilie J. Rutledge who, with almost two decades’ worth of experience in managing, designing and delivering university-level economics courses, is currently Head of the Economics Department at The Open University.

erutledge.com  Dr Emilie J. Rutledge Emilie has published over 20 peer-reviewed papers and is the author of “Monetary Union in the Gulf.” Her current research focus is on employability, the feasibility of universal basic incomes and, the oil-rich Arabian Gulf’s economic diversification and labour market reform strategies. On an ad hoc basis, Emilie provides consultancy on developing interactive university courses, alongside analytical insight on the political-economy of the Arabian Gulf. |