Country Profiles

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Arab Emirates

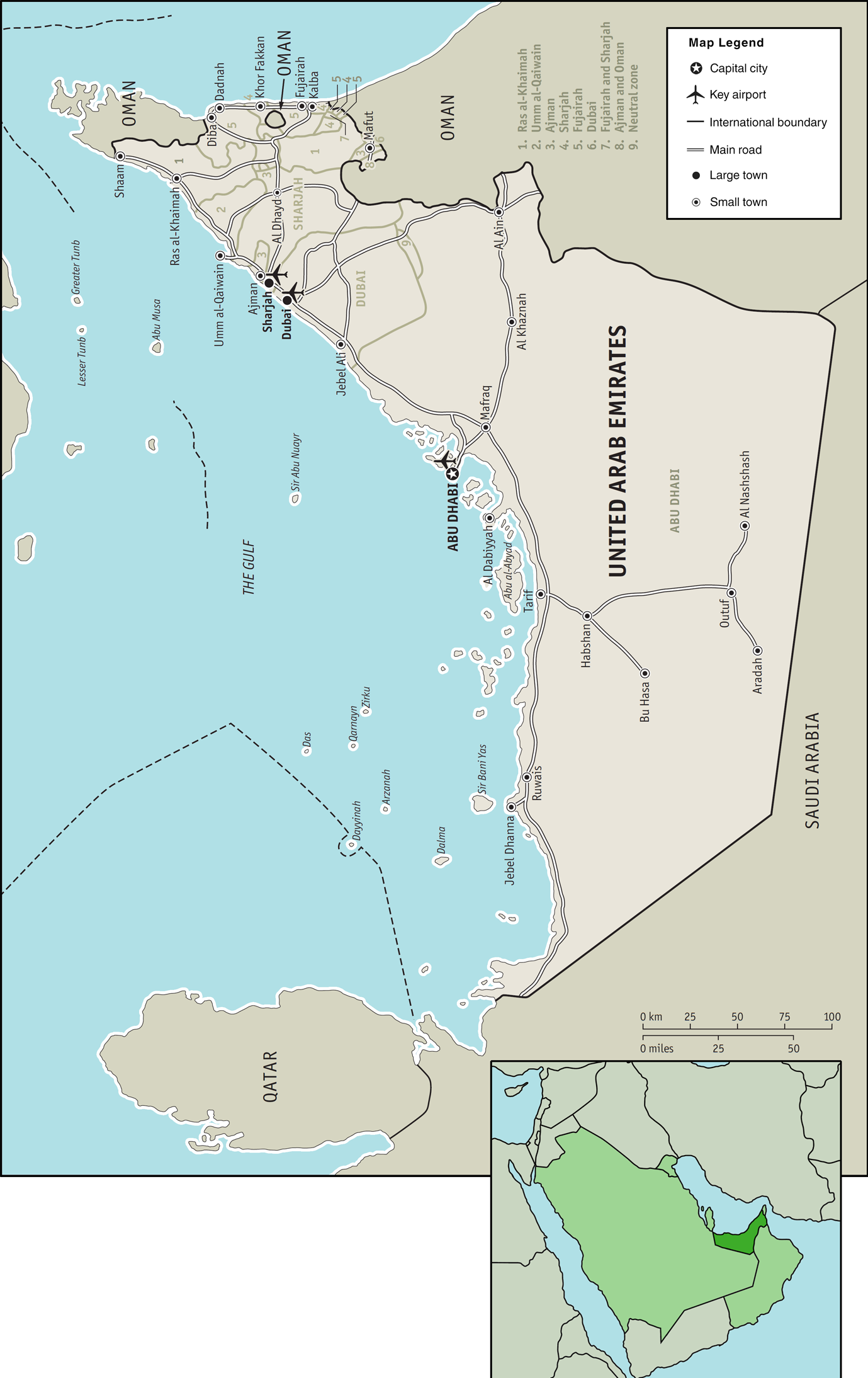

The United Arab Emirates, ‘the UAE,’ or simply ‘the Emirates,’ is at the eastern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a federal elective monarchy made up of seven emirates, with Abu Dhabi serving as its capital. The seven Emirates are: Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain, Ras Al Khaimah and Fujairah. The UAE shares land borders with Oman to the east and northeast, and with Saudi Arabia to the southwest; as well as maritime borders in the Persian Gulf with Qatar and Iran, and with Oman in the Gulf of Oman.

Maps & Flag

As of 2025, the UAE had an estimated population of 12.2 million, of which just one million were Emiratis. Thus, less than one in ten individuals in the UAE have claims to the country’s sovereign wealth.

Introduction

The UAE economy experienced a significant slowdown to 3.1 per cent in GDP growth in 2023, down from 7.9 per cent in 2022. The deceleration was attributed to weaker economic global activities and a decline in oil production to comply with OPEC+ decisions. As a result, the oil sector has witnessed a contraction of an estimated 2.7 per cent. However, “the non-oil sector, however, remains robust and resilient as growth accelerates to 5.4 per cent, driven by the financial and insurance services, construction, real estate, and wholesale and retail trade sectors” (World Bank, 2024a). The following summary of the UAE’s economy was given by the World Bank in 2024:

The UAE maintains its status as a key regional hub for trade, finance, and tourism, bolstered by substantial progresses in economic diversification and a reduced dependence on hydrocarbon income. Major risks to the outlook include an escalation of geopolitical conflicts, large fluctuations in oil prices, and continued global financing tightening.

In general, hydrocarbon activity remains the primary source of government revenue, but efforts are underway to accelerate the diversification of the economy and of government revenues. These include the introduction of Corporate Income Tax (CIT) in mid-2023. The outlook for the non-oil sector is robust, with an anticipated increase in oil sector activity expected to maintain strong external and fiscal positions. Key risks to growth include OPEC+ decisions on quotas, as well as the continuation/expansion of the conflict in the Middle East and its potential impact on oil prices volatility and on the movement of goods and people (not least, tourism). In particular, the disruption of trade routes in the Red Sea have triggered an increase in shipping costs and rerouting, including for Asia-Europe trade. This could negatively impact the transport and logistics sectors, posing potential downside risks to economic growth during 2025.

Political-Economy

According to the EIU (2024) Strong international oil prices have enabled the government of the UAE to continue to invest heavily in improving infrastructure and maintaining targeted social support, housing and employment assistance, and other benefits. In general, a high level of income per head and redistribution of funds between Abu Dhabi and less wealthy emirates in the UAE mean that there are fewer social strains or demands for democratisation than in poorer countries with comparable authoritarian political systems. In the EIU’s annual Democracy Index, the UAE was placed, “firmly in the “authoritarian” category, ranked 125th out of 167 countries and territories. [1]

As Reporters Without Boarders (Reporters sans frontières, RSF) wrote in 2024, the government of the UAE “prevents both local and foreign independent media outlets from thriving by tracking down and persecuting dissenting voices.” Under a 1980 federal law, UAE authorities can censor media content deemed to be overly critical of policies, the ruling families, religion or the economy. Journalists are also targeted under the 2012 cybercrime law, which was updated in 2021. In addition, spreading “rumours” is punishable by a prison sentence as well as a fine. The National Media Council regulates the media and hunts down content that criticises government decisions or threatens “social cohesion” – terms vague enough to include any content that does not conform to government requirements. The National Media Council also examines and sanctions foreign media content, which is subject to national standards.

There is a tradition of loyalty to the House of Nahyan, the UAE’s founding family, that is linked to the country’s historical development and its emergence as an economic power. Any criticism of its members is condemned and seen as a lack of loyalty. This encourages self-censorship. “As soon as they emit the slightest criticism, journalists and bloggers find themselves in the crosshairs of the UAE’s authorities, who are masters of online surveillance. Offenders are usually accused of defamation, insulting the state or spreading false information designed to harm the country’s image. For this, they risk long prison sentences and are likely to be mistreated.”

Freedom House (2024) provides the following summary for the UAE:

Limited elections are held for a federal advisory body, but political parties are banned, and all executive, legislative, and judicial authority ultimately rests with the seven hereditary rulers. The civil liberties of both citizens and noncitizens are subject to significant restrictions.

According to Human Rights Watch (2024), “unjustly convicted and sentenced at least 44 defendants in the second largest unfair mass trial, many of whom had already been serving prison sentences as part of the UAE94 mass trial.” The UAE has promoted a public image of tolerance and openness through hosting events like COP28 while restricting scrutiny of its rampant systemic human rights violations and fossil fuel expansion (Human Rights Watch, 2024). HRW add that the UAE’s kafala (labour sponsorship) system ties migrant workers’ visas to their employers, preventing them from changing or leaving employers without permission:

Employers can falsely charge workers for “absconding” even when escaping abuse, which puts them at risk of fines, arrest, detention, and deportation, all without any due process guarantees. Many low-paid migrant workers were acutely vulnerable to situations that amount to forced labor, including passport confiscation, wage theft, and illegal recruitment fees. Trade unions are not permitted, which prevents workers from collectively bargaining. The UAE still does not have a non-discriminatory minimum wage.

Moreover:

The UAE deploys some of the world’s most advanced surveillance technologies to pervasively monitor public spaces, internet activity, and even individuals’ phones and computers, in violation of their right to privacy, freedom of expression, freedom of association, and other rights. The authorities block and censor content online that they perceive to be critical of the UAE’s rulers, government, and policies and any topic, whether social or political, that authorities may deem sensitive. The penal code and Cybercrime Law further curtail space for dissent. Article 174 of the penal code stipulates a minimum prison sentence of five years and a minimum fine of approximately $27,000 if the act takes place in “writing, speech, drawing or by statement or using any means of technology or through the media.” Two provisions may directly affect the work of journalists based in the UAE. Article 178 provides for sentences of three to 15 years in prison for anyone who, without a license from the appropriate authorities, collects “information, data, objects, documents, designs, statistics or anything else for the purpose of handing them over to a foreign country or group or organization or entity, whatever its name or form, or to someone who works in its interest.” The Cybercrime Law contains an entirely new section entitled, “Spreading Rumors and False News.”

Graphs & Tables

What follows are a selection of graphs and tables from credible and cited sources. It is worth comparing those on the UAE with those of the other Arabian Gulf countries covered on this site.

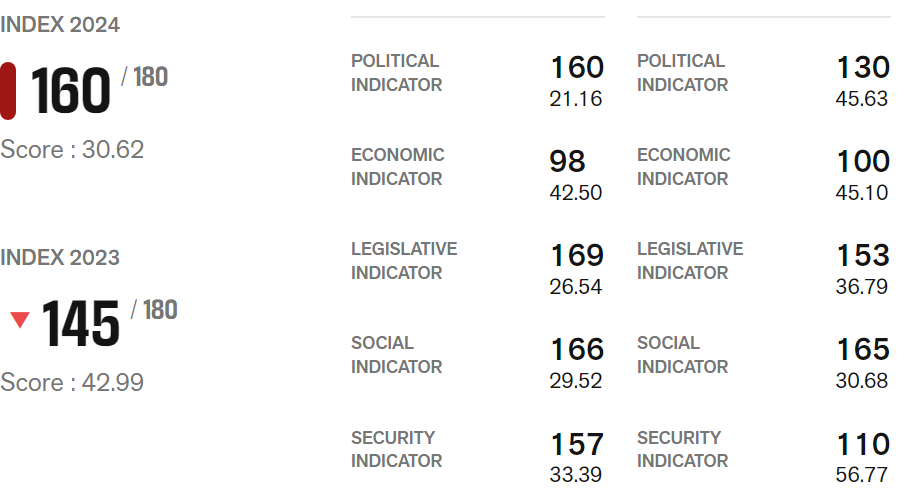

RSF contend that it is the right of every human being to “have access to free and reliable information.” The Press Freedom Index, use five contextual indicators for each economy assessed: political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context and safety (whereby a subsidiary score ranging from 0 to 100 is calculated for each indicator):

Press freedom in the United Arab Emirates

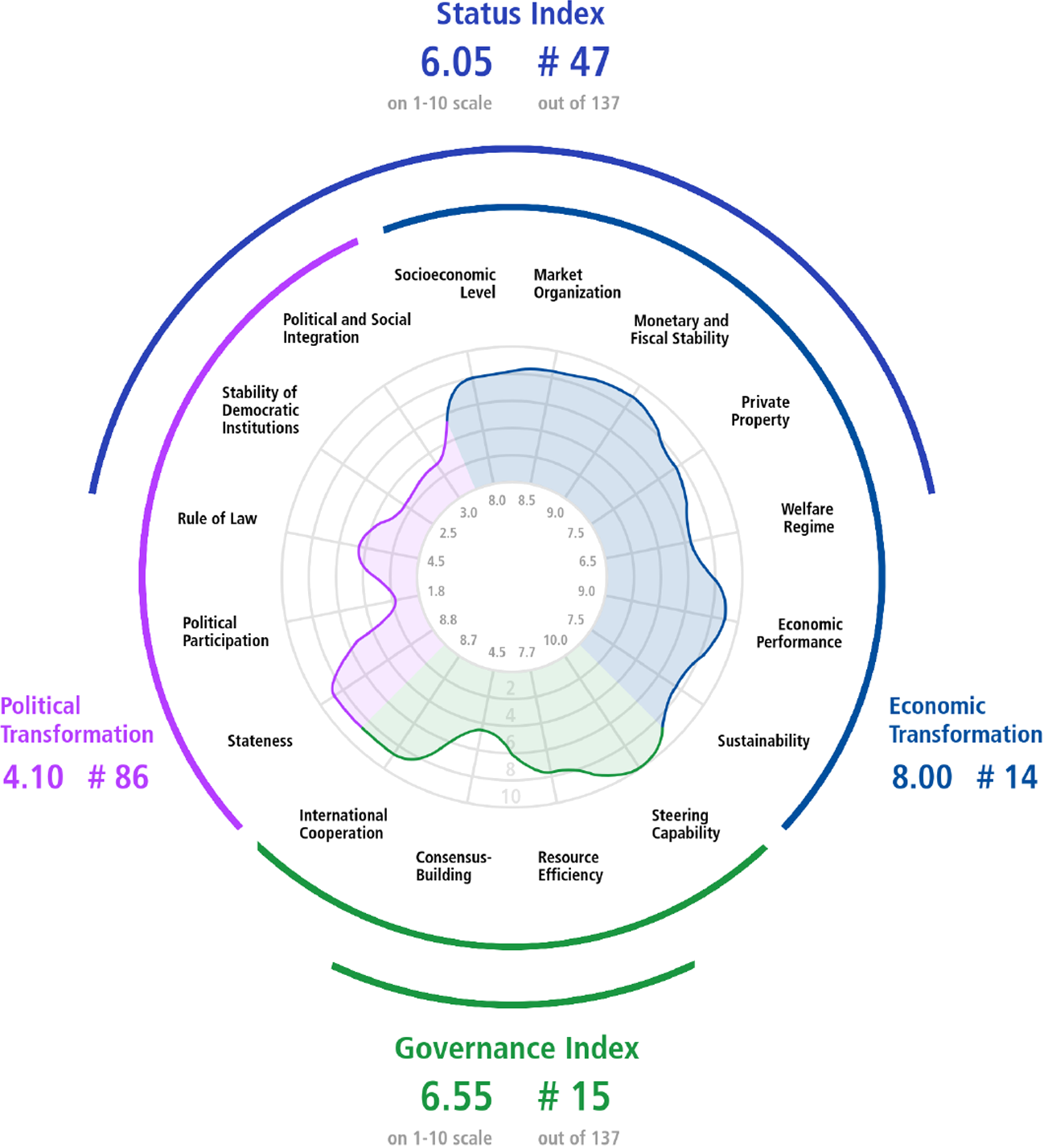

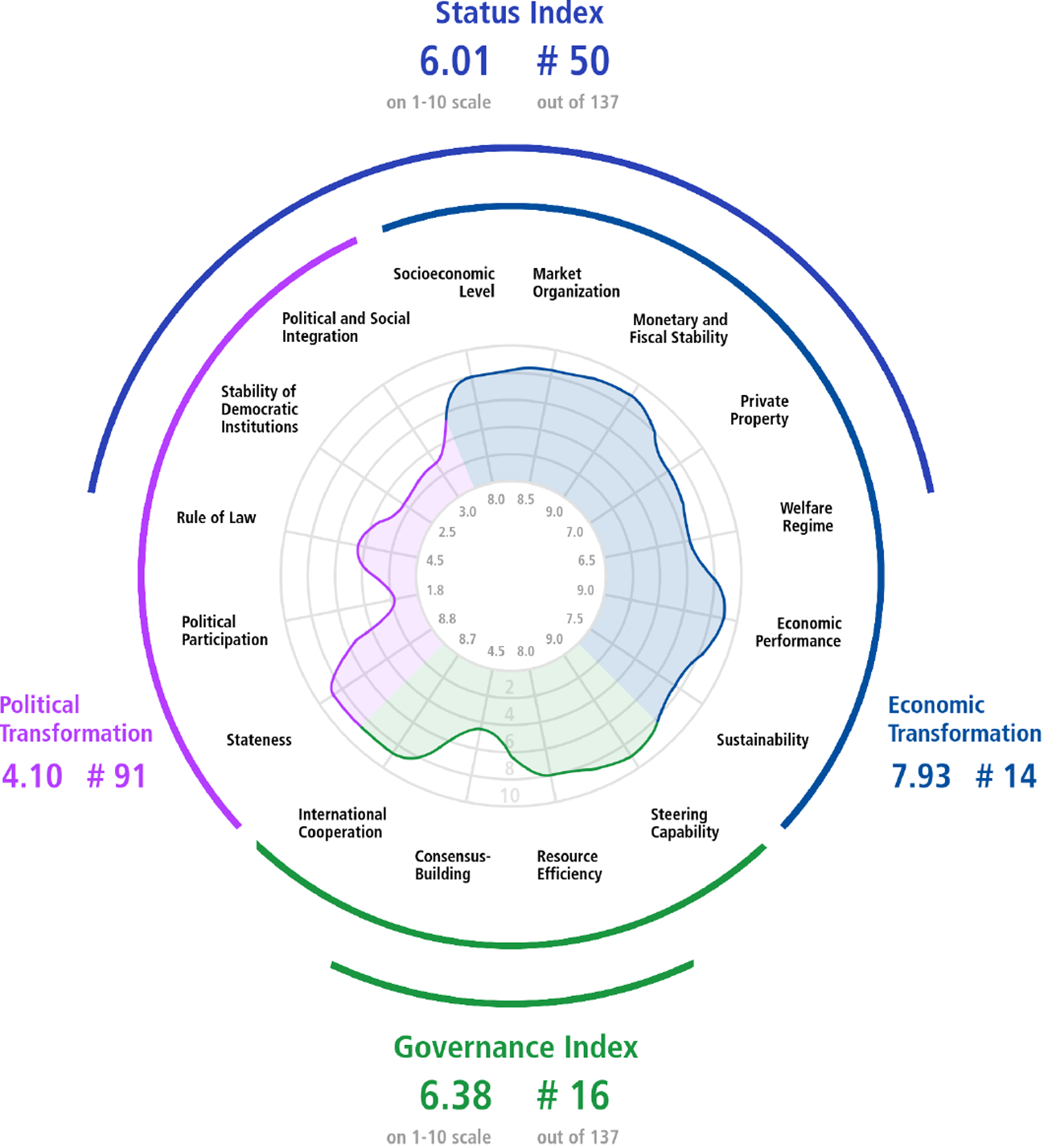

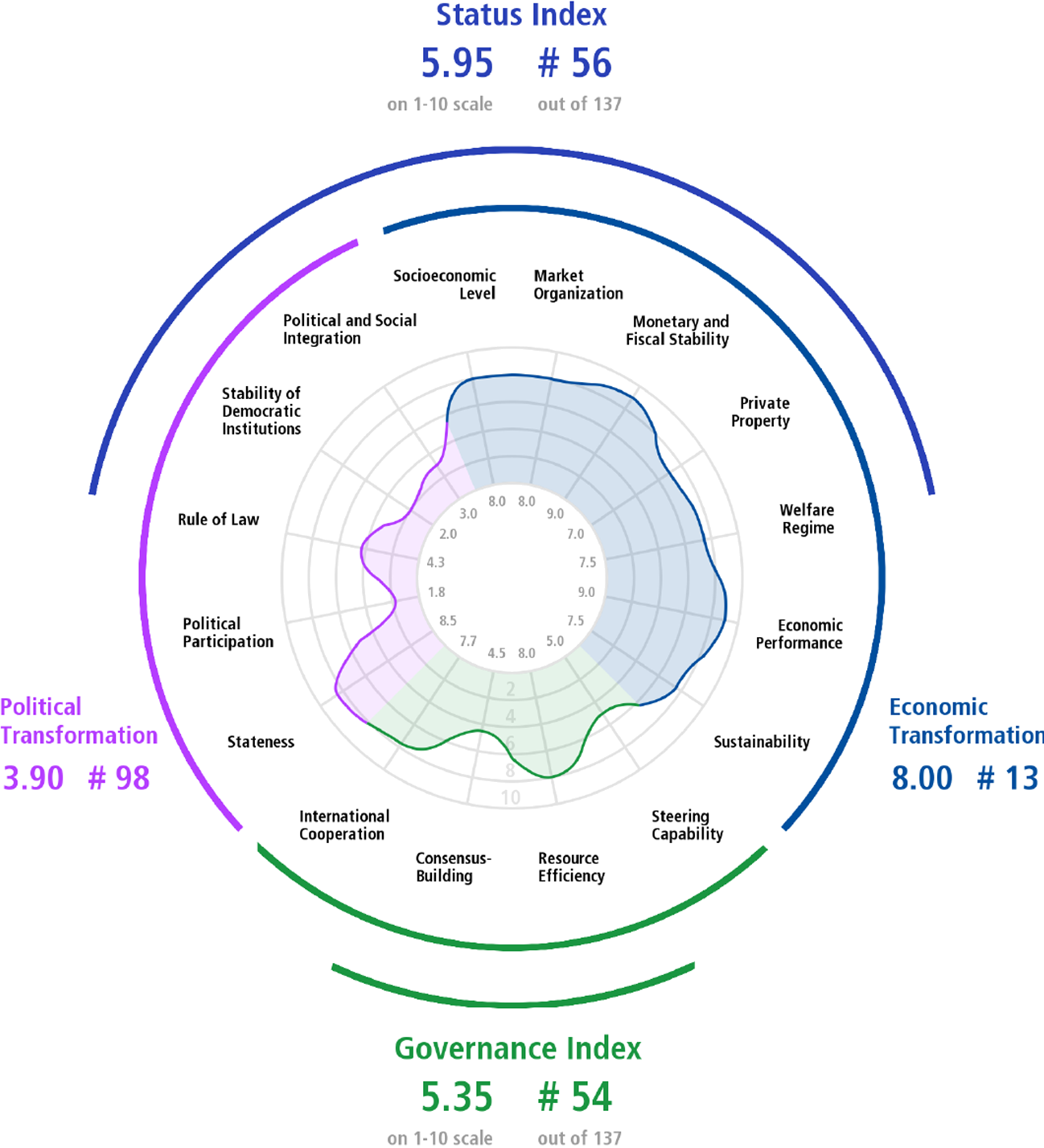

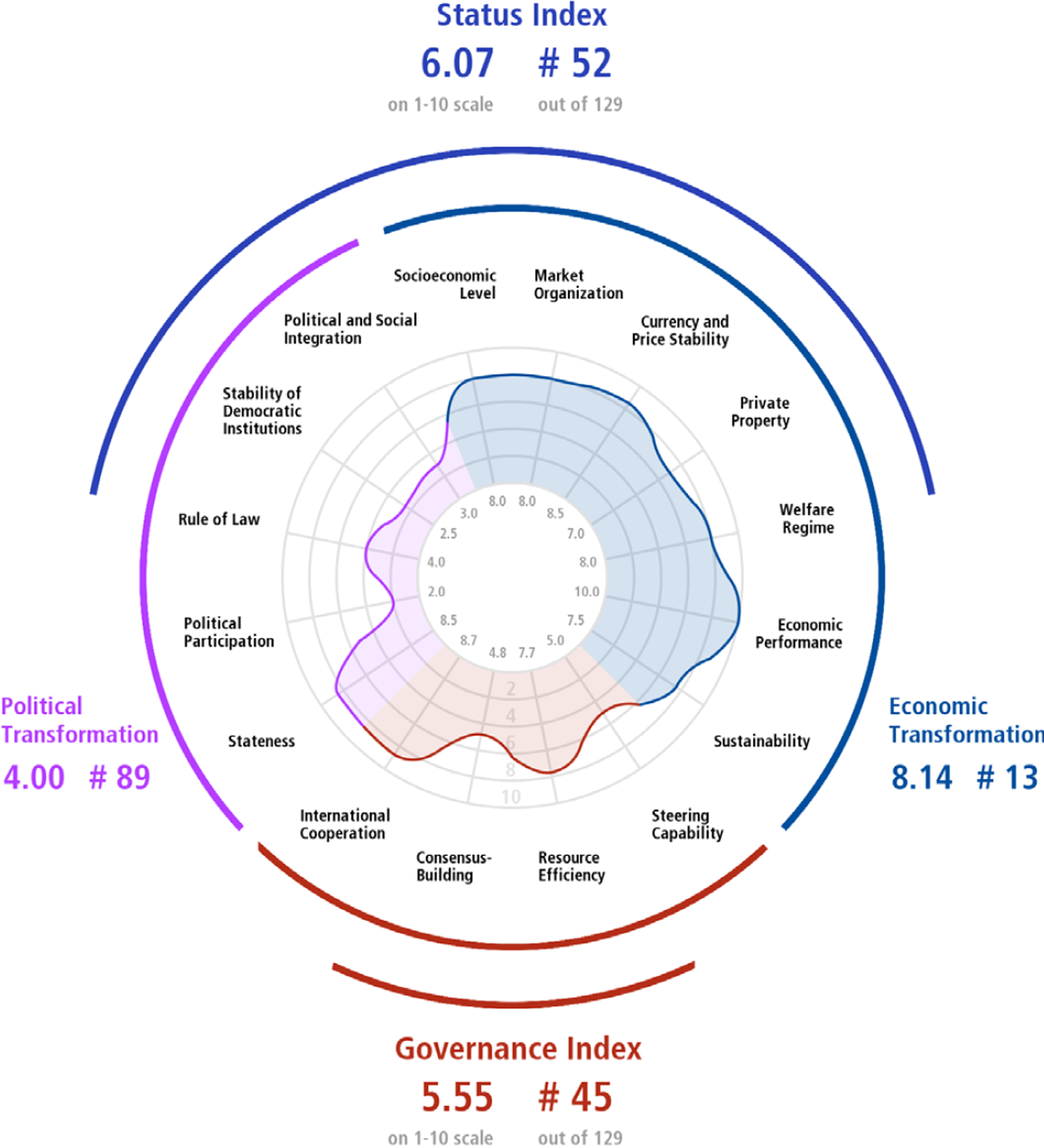

Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index analyses the transformation processes toward democracy in transitional economies across the globe. In 2024 it was stated that throughout MENA, “autocratic rule festers” and that MENA’s scores for democracy and the quality of governance are at “all-time lows” and that “the quality of governance is deteriorating, and military forces are gaining power.” The German Non-governmental organisation adds that many countries within this region on “flashy imagery and marketing under the banner of modernisation, rather than making actual progress (BTI, 2024). BTI (2024) also point out that MENA’s scores for democracy and the quality of governance are at an all-time low [and] the quality of governance is deteriorating, and military forces are gaining power. The German NGO adds that many countries rely on “flashy imagery and marketing under the banner of modernisation,” rather than making actual progress.

United Arab Emirates, BTI 2024 scores

Expand Chart →

UAE’s 2024 BTI matrix:

UAE’s 2022 BTI matrix:

UAE’s 2020 BTI matrix:

UAE’s 2018 BTI matrix:

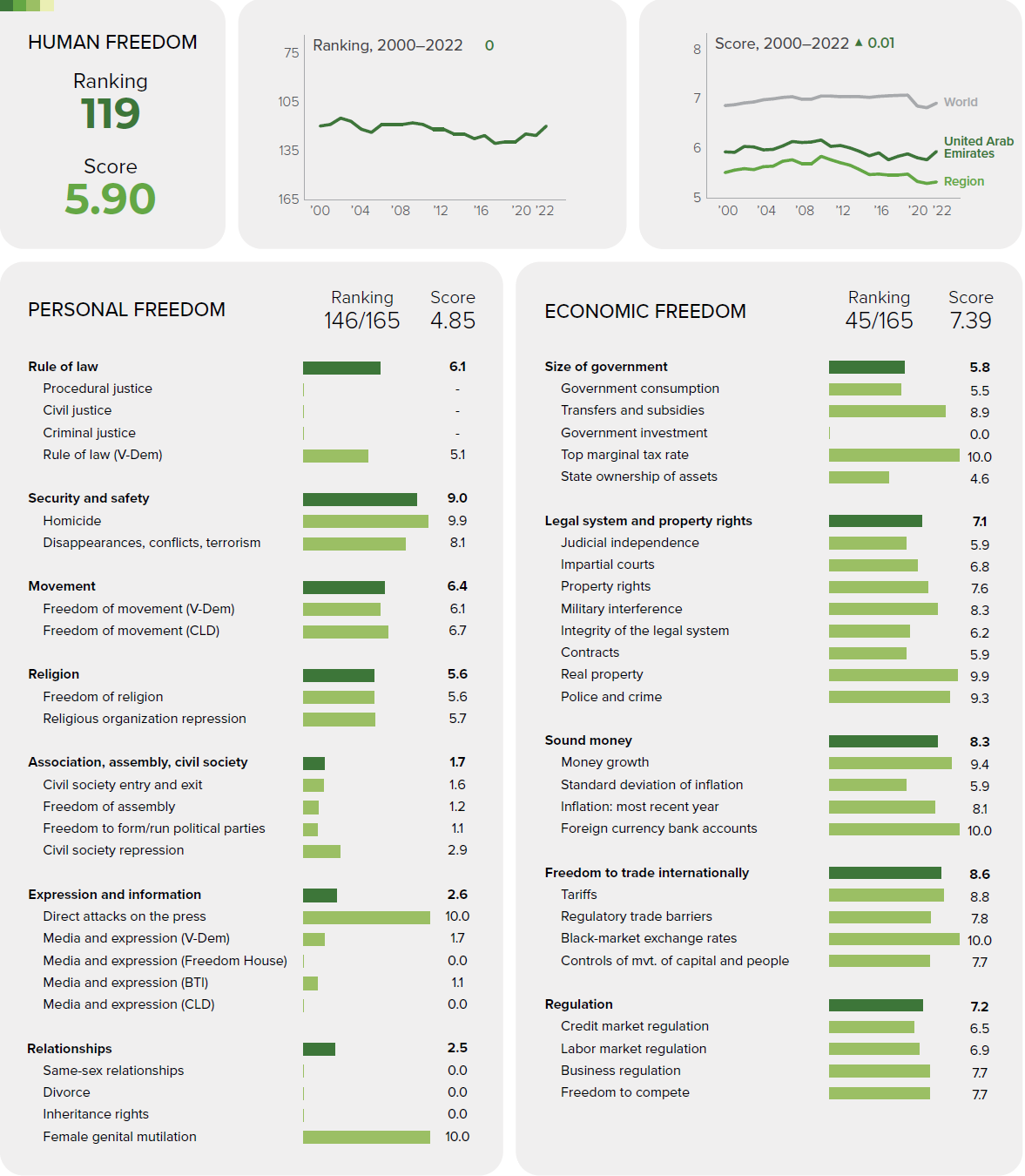

Fraser Institute rankings

The Fraser Institute’s Human Freedom Index presents a broad measure of human freedom, understood as the absence of coercive constraint.

The United Arab Emirates, Freedom in the World, 2024 scores

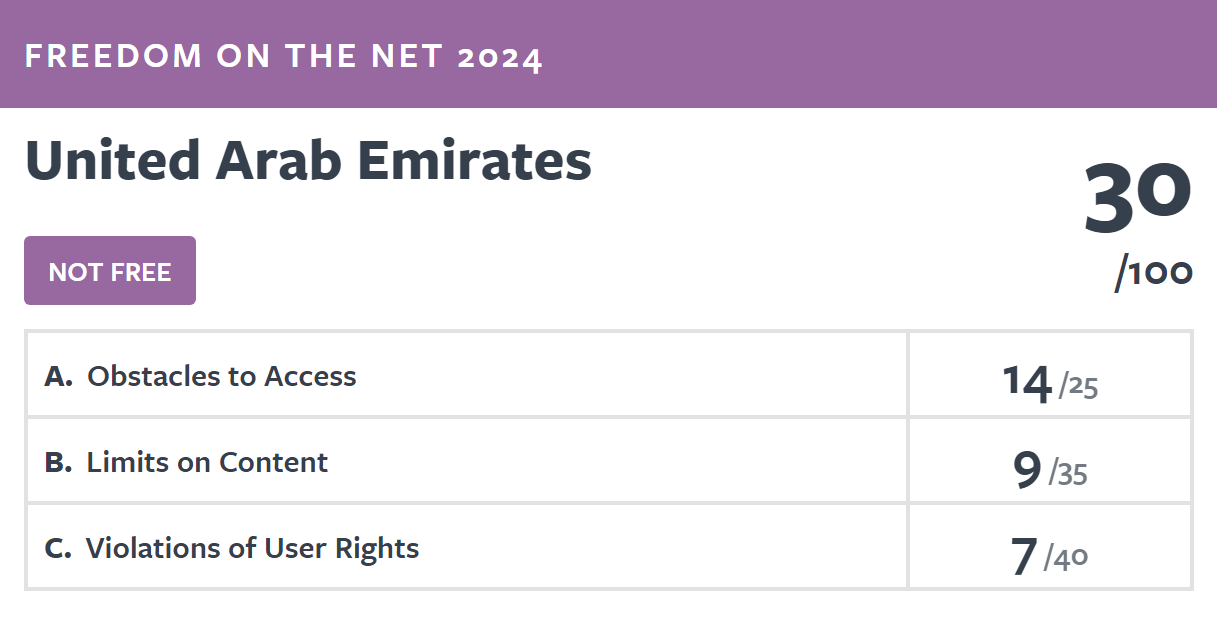

Freedom House rankings

Freedom House point out that their Freedom in the World annual rankings are “the most widely read and cited report of its kind, tracking global trends in political rights and civil liberties for over 50 years.” They chart Global Freedom scores and Internet Freedom scores for some 210 countries and territories. More latterly, Freedom House have begun to chart Internet Freedom scores (currently 70 countries are tracked, of which three are in the Arabian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates).

The United Arab Emirates, Freedom in the World, 2024 scores

notes

Country profile information is compiled from, amongst others, the following sources; a full References list for this page is also given below:

Academic

Cambridge University Press →

Cambridge University Press →

Intellect Discover →

Intellect Discover →

Oxford Academic →

Oxford Academic →

Routledge →

Routledge →

Sage →

Sage →

Springer →

Springer →

Media outlets

The Economist Intelligence Unit →

The Economist Intelligence Unit →

Financial Times →

Financial Times →

Middle East Economic Digest →

Middle East Economic Digest →

Organisations

Arab Monetary Fund →

Arab Monetary Fund →

Bertelsmann Transformation Index →

Bertelsmann Transformation Index →

Energy Information Agency →

Energy Information Agency →

Energy Institute →

Energy Institute →

Eurostat →

Eurostat →

Fraser Institute →

Fraser Institute →

Freedom House →

Freedom House →

International Energy Agency →

International Energy Agency →

International Monetary Fund →

International Monetary Fund →

Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries →

Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries →

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development →

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development →

Reporters sans frontières →

Reporters sans frontières →

United Nations Development Program →

United Nations Development Program →

Varieties of Democracy →

Varieties of Democracy →

The World Bank →

The World Bank →

World Economic Forum →

World Economic Forum →

World Intellectual Property Organisation →

World Intellectual Property Organisation →

World Trade Organisation →

World Trade Organisation →

References

Al Shouk, A. (2024, June 20). Emiratisation deadline looms as larger private companies look to fulfil national targets. The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/news/uae/2024/06/20/emiratisation-deadline-july/

Arab Monetary Fund. (2025). Economic Statistics [Dataset]. https://www.amf.org.ae/en/arabic_economic_database

Asker, J., Collard-Wexler, A., & De Loecker, J. (2017). Market power, production (mis)allocation and OPEC. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper Series, 1(September, w23801), 1–54. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23801

Assidmi, L. M., & Wolgamuth, E. (2017). Uncovering the Dynamics of the Saudi Youth Unemployment Crisis. Systemic practice and action research, 30(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-016-9389-0

Baumeister, C., & Kilian, L. (2016). Forty Years of Oil Price Fluctuations: Why the Price of Oil May Still Surprise Us. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(1), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.1.139

Bekhradnia, B. (2016). International university rankings: For good or ill? Higher Education Policy Institute, 1(89), 1–32.

Benítez-Márquez, M.-D., Sánchez-Teba, E. M., Coronado-Maldonado, I., & Sung, W.-W. (2022). An alternative index to the global competitiveness index. PloS one, 17(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265045

Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2024). BTI 2004-2024 Country Reports [Dataset: Bertelsmann Transformation Index]. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/global-dashboard

BP. (2022). Statistical Review of World Energy. British Petroleum.

Bradshaw, T. (2022). [Book Review] Davidson, C. “From Sheikhs to Sultanism: Statecraft and Authority in Saudi Arabia and the UAE”. Middle Eastern Studies, 58(1), 687–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2021.2017288

Caldara, D., Cavallo, M., & Iacoviello, M. (2019). Oil price elasticities and oil price fluctuations. Journal of Monetary Economics, 103(May), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2018.08.004

Chirikov, I. (2023). Does conflict of interest distort global university rankings? Higher Education, 86(4), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00942-5

Cooley, A., & Snyder, J. (Eds.). (2015). Ranking the World: Grading States as a Tool of Global Governance. Cambridge University Press.

Cortés, P., Kasoolu, S., & Pan, C. (2023). Labor Market Nationalization Policies and Exporting Firm Outcomes: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Economic development and cultural change, 71(4), 1397–1426. https://doi.org/10.1086/719835

EIA. (2024). International, Petroleum and other liquids [Dataset: U.S. Energy Information Administration]. https://www.eia.gov/international/data/

EIA. (2025). Real Petroleum Prices [Dataset: Energy Information Agency]. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/realprices/

EIU. (2024). Democracy Index 2023: Age of conflict. Economist Intelligence Unit. https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2023/

EIU. (2025). EIU Democracy Indices, 2018-2023 [Dataset: EIU Democracy Indices]. Economist Intelligence Unit.

Energy Institute. (2024). Statistical Review of World Energy [Dataset]. https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review/resources-and-data-downloads

Eurostat. (2025). Database [Dataset]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

Fraser Institute. (2024). The Human Freedom Index. The Fraser Institute.

Freedom House. (2024a). Freedom on the Net [Dataset]. https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-net/scores

Freedom House. (2024b). World Freedom Index [Dataset]. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world#Data

Global Media Insight. (2024). UAE Population 2024 (Key Statistics). Global Media Insight. https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/uae-population-statistics/

Global SWF. (2024). Countries Ranking [Dataset]. https://globalswf.com/countries

Government of Bahrain. (2024). The National Labour Market Plan 2023-2026. Labour Market Regulatory Authority.

Government of Bahrain. (2025). Open Data Portal [Dataset]. Information & eGovernment Authority. https://www.data.gov.bh/

Government of Dubai. (2022). Number of Population Estimated by Nationality [Dataset]. https://www.dsc.gov.ae/en-us/Themes/Pages/Population-and-Vital-Statistics.aspx?Theme=42

Government of Kuwait. (2018). Decent Work: Country Programme For Kuwait. Government of Kuwait.

Government of Kuwait. (2024). Labour Market Statistics [Dataset: Central Statistical Bureau]. https://www.csb.gov.kw/Pages/Statistics_en?ID=64&ParentCatID=1

Government of Kuwait. (2025). Open Data [Dataset]. https://e.gov.kw/sites/kgoenglish/Pages/OtherTopics/OpenData.aspx

Government of Oman. (2022). Skills needs in the Oman labour market: An employer survey. Oman Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Government of Oman. (2025). Population statistics [Dataset: National Centre For Statistics & Information]. https://data.gov.om/

Government of Qatar. (2025). Open Data Portal [Dataset: Planning and Statistics Authority]. https://www.data.gov.qa

Government of Saudi Arabia. (2024). Labour Market Statistics [Dataset: General Authority for Statistics]. https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/814

Government of the United Arab Emirates. (2025). Open Data [Dataset]. Ministry of Economy. https://www.moec.gov.ae/en/open-data

Gulf Research Centre. (2024). Gulf Labour Markets, Migration and Population programme [Dataset]. https://gulfmigration.grc.net/

Gunitsky, S. (2015, June 23). How do you measure ‘democracy’? The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/06/23/how-do-you-measure-democracy/

Hazelkorn, E. (2019). University Rankings: there is room for error and “malpractice”. Elephant in the Lab. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2592196

Herre, B. (2024). Democracy data: how sources differ and when to use which one. OurWorldinData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/democracies-measurement

Hertog, S. (2018). Can we Saudize the labour market without damaging the private sector? Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/101471

Hertog, S. (2024). The Political Economy of Reforms under Vision 2030. In J. Sfakianakis (Ed.), The Economy of Saudi Arabia in the 21st Century: Prospects and Realities (pp. 359–380). Oxford University Press.

IEA. (2025). Data and statistics [Dataset: The International Energy Agency]. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-sets

Ikenberry, G. J. (2015). Ranking the World: Grading States as a Tool of Global Governance [Book Review]. Foreign Affairs, 94(5), 180–180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24483753

IMF. (2023). Kuwait: 2023 Article IV Consultation. IMF Staff Country Reports, 2023(331). https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400254680.002

IMF. (2024a). Gulf Cooperation Council: Pursuing Visions Amid Geopolitical Turbulence. International Monetary Fund working papers, 2024(66), 1–74. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400295744.007

IMF. (2024b). Qatar: 2023 Article IV Consultation. IMF Country Report, 2024(24/43). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2024/02/06/Qatar-2023-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-and-Staff-Report-544471

IMF. (2024c). Saudi Arabia: 2024 Article IV Consultation. IMF Staff Country Reports, 2024(323). https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400252099.002

IMF. (2024d). United Arab Emirates: 2024 Article IV Consultation. IMF Staff Country Reports, 2024(325). https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400293245.002

IMF. (2024e). World Economic Outlook [Dataset]. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April

IMF. (2025). Oman: 2024 Article IV Consultation. IMF Staff Country Reports, 2025(13). https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400298318.002

Kashyap, A. K., & Kovrijnykh, N. (2016). Who Should Pay for Credit Ratings and How? The Review of financial studies, 29(2), 420–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhv127

Lopesciolo, M., Muhaj, D., & Pan, C. (2021). The quest for increased Saudization: Labor market outcomes and the shadow price of workforce nationalisation policies. Retrieved from https://growthlab.hks.harvard.edu/publications/quest-increased-saudization-labor-market-outcomes-and-shadow-price-workforce

Nair, D. (2024, May 13). What roles are Emiratis being hired for in the private sector? The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/money/2024/05/13/emiratis-hired/

OECD. (2025). OECD Data Explorer [Dataset]. https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/oecd-DE.html

OPEC. (2024). Annual Statistical Bulletin. Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Polity IV. (2018). Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2018 [Dataset: Center for Systemic Peace]. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/p4v2018.xls

Poplavskaya, A., Karabchuk, T., & Shomotova, A. (2023). Unemployment Challenge and Labor Market Participation of Arab Gulf Youth: A Case Study of the UAE. In M. M. Rahman & A. Al-Azm (Eds.), Social Change in the Gulf Region: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 511–529). Springer Nature Singapore.

Porter, M. E. (1998). Competitive Advantage of Nations. Simon & Schuster.

Reporters Without Borders. (2024). Press Freedom Index [Dataset: Press Freedom Index]. https://rsf.org/en/index

Rutledge, E. J., & Al Kaabi, K. (2023). ‘Private sector’ Emiratisation: social stigma’s impact on continuance intentions. Human Resource Development International, 26(5), 603–626. https://10.1080/13678868.2023.2182097

Shore, C. (2018). How Corrupt Are Universities? Audit Culture, Fraud Prevention, and the Big Four Accountancy Firms. Current Anthropology, 59(18), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1086/695833

The Economist. (2020, May 7). Credit-rating agencies are back under the spotlight. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/05/07/credit-rating-agencies-are-back-under-the-spotlight

The Times of Kuwait. (2024, August 24). Kuwaiti workforce grows to 457,567. The Times of Kuwait. https://timeskuwait.com/kuwaiti-workforce-grows-to-457567-makes-up-21-3-of-labor-market/

UNDP. (2024). Human Development Index [Dataset: The United Nations Development Program]. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center

UNDP. (2025). Human Development Index (HDI). The United Nations Development Program. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI

V-Dem. (2024). V-Dem [Dataset: University of Gothenburg, Department of Political Science]. https://doi.org/10.23696/mcwt-fr58

Vaccaro, A. (2021). Comparing measures of democracy: statistical properties, convergence, and interchangeability. European political science, 20(4), 666–684. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00328-8

WEF. (2019). The Global Competitiveness Indices. The World Economic Forum. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2019.pdf

WEF. (2025). The Global Competitiveness Indices, 2008–2019 [Dataset: Global Competitiveness Indices]. The World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/publications/series/

WIPO. (2024). Global Innovation Index [Dataset: UN, The World Intellectual Property Organisation]. https://www.wipo.int/en/web/global-innovation-index

World Bank. (2024a). Macro Poverty Outlook [Dataset]. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099345310142441749/

World Bank. (2024b). Worldwide Governance Indicators [Dataset]. https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/sites/govindicators/

World Bank. (2025a). World Development Indicators [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org/

World Bank. (2025b). Worldwide Governance Indicators – Data Sources. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators/

WTO. (2025). WTO Stats [Dataset: World Trade Organisation]. https://stats.wto.org/dashboard/merchandise_en.html

The Six GCC Economies:

|

|

|

|

|

|

| i | This is the website of Dr Emilie J. Rutledge who, with almost two decades’ worth of experience in managing, designing and delivering university-level economics courses, is currently Head of the Economics Department at The Open University.

erutledge.com  Dr Emilie J. Rutledge Emilie has published over 20 peer-reviewed papers and is the author of “Monetary Union in the Gulf.” Her current research focus is on employability, the feasibility of universal basic incomes and, the oil-rich Arabian Gulf’s economic diversification and labour market reform strategies. On an ad hoc basis, Emilie provides consultancy on developing interactive university courses, alongside analytical insight on the political-economy of the Arabian Gulf. |

Elsevier

Elsevier