The Economist (2016). Time to sheikh it up. The Economist, 420(9006), 11–12. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2016/09/08/time-to-sheikh-it-up

THE people of Saudi Arabia have for decades enjoyed the munificence of their royal family: no taxes; free education and health care; subsidised water, electricity and fuel; undemanding jobs in the civil service; scholarships to study abroad; and much more. This easy life has been sustained by gushers of petrodollars and an army of foreign workers. The only thing asked of subjects is public observance of Islamic strictures and acquiescence in the absolute power of the sprawling Al Saud dynasty.

Similar arrangements hold in the other countries of the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC), a six-member club of oil monarchies. But these compacts are breaking down. The price of oil has fallen sharply since 2014, and the number of young Gulf citizens entering the job market is growing fast. The maliks and emirs can no longer afford huge giveaways, or to pay ever more subjects to snooze in air-conditioned government offices. The monarchs know it. They say they are seeking to diversify their economies away from oil rents; they are also whittling away generous subsidies and plan a new value-added tax across the GCC.

But reforms have to go further. If Gulf citizens are to keep enjoying rich-world standards of living, they will increasingly have to find productive work in the private sector. That means overhauling labour markets that keep too many of the region’s citizens idle.

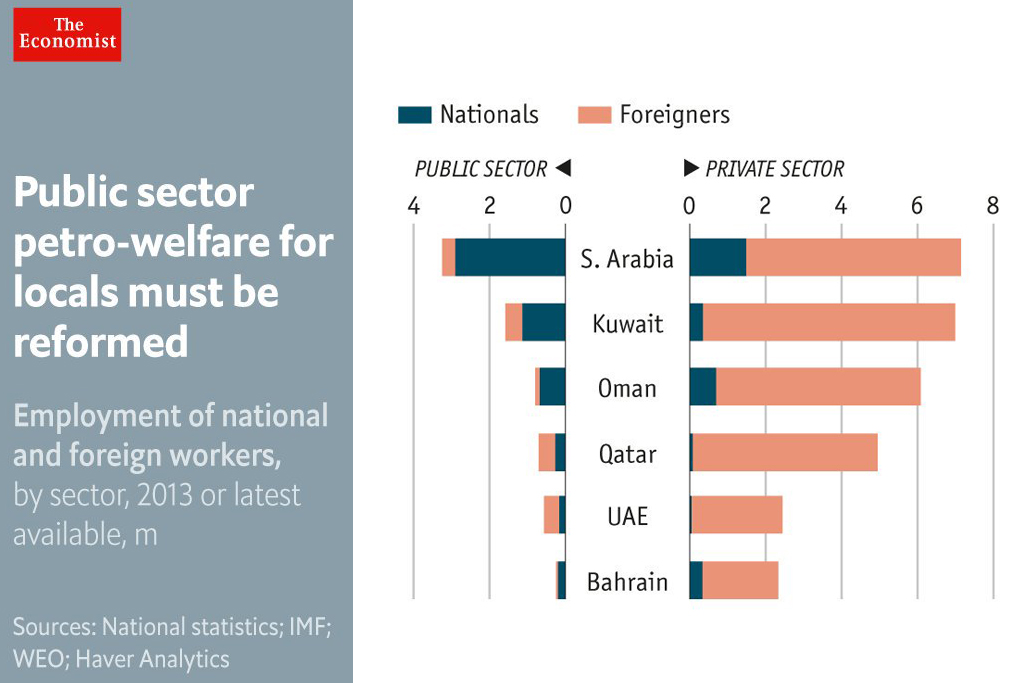

The pampering of Gulf citizens has made them expensive for firms to hire (see “Labour laws in the Gulf: From oil to toil”). By contrast, the third-class legal status of many migrant workers makes them extra-cheap (see “Migration in the Gulf: Open doors but different laws”) and puts them at the mercy of their employers. Given the choice between a hardworking foreigner and a costly local, private firms have long preferred the foreigner.

In response Gulf governments have imposed ever more stringent quotas on foreign companies to employ locals, especially in desirable white-dishdasha jobs. In Bahrain 50% of workers in banks must be Bahrainis; but only 5% of those in construction need be. (It’s awfully hot on building sites.) Quotas reduce the incentive for Gulf citizens to do a job well: why bother, when your employer has little choice but to keep you on? Firms often regard hiring locals as a sort of tax. Some pay them to stay at home.

The best policy would be to phase out quotas entirely, while also slimming the bureaucracy and making it clear that civil-service jobs are no longer a birthright. In Saudi Arabia two-thirds of citizens are employed by the state. Public-sector wages account for 12% of GDP in the Gulf and Algeria, compared with an average of 5% across emerging economies.

The way migrant labourers are treated needs to change, too. Gulf states deserve credit for letting in far more immigrants than almost all Western countries, relative to their populations. (In many cases, foreigners outnumber locals.) Migrants gain from earning far higher wages than they could back in India or Pakistan. But the coercive parts of the kafala system of sponsoring foreign workers should be dismantled. Migrant workers should not need their employers’ permission to leave the country. After a while, they should be allowed to switch jobs. Contracts should be clear and enforced by local courts. Long-term foreign workers should be able to earn permanent residence; ultimately those who wish to should have the opportunity to become citizens.

These reforms–less pampering for locals and more rights for migrants–would reshape the labour market. More locals would have to do real work. Migrants would be better treated, though inevitably fewer would be hired. Some new ideas are being tested. Bahrain is allowing firms to ignore quotas by paying a fee for each foreign worker they employ. As part of its ambitious economic agenda, Saudi Arabia is talking of issuing green cards to some migrants.

A new social contract

At a time of bloody turmoil across the Arab world, many royals fear undoing the social compact that has kept them in power. But cheap oil makes change unavoidable; doing nothing merely postpones the reckoning. Economic transformation should nudge Gulf states towards political reform. Perhaps, as their citizens are asked to do more to earn their living, they will demand that rulers do more to earn their consent.