In a 2023 article for the Wall Street Journal (Said et al., 2023), it was revealed that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) “has pulled away from his former mentor [U.A.E. President Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan; MBZ] as they compete to dominate the Gulf, where U.S. power has waned.” The rift, it is said, reflects a competition for geopolitical and economic power in the Middle East and global oil markets. The two royals — photoed together above — who spent almost a decade climbing to the top of the Arab world, are now feuding over who calls the shots.”

The two countries are also increasingly economic competitors. As part of MBS’s plans to end Saudi Arabia’s economic reliance on oil, he is pushing companies to move their regional headquarters to Riyadh, the Saudi capital, from U.A.E.’s Dubai, a more cosmopolitan city favored by Westerners. He’s also launching plans to set up tech centers, draw more tourists and develop logistical hubs that would rival the U.A.E.’s position as the Middle East’s center of commerce . In March, he announced a second national airline that would compete with Dubai’s highly ranked Emirates.

Allocating resource wealth (a.k.a, “oil-rent”)

📕 “Arabian Gulf sovereign wealth” →

Said et al. (2020) site Gulf officials as saying that MBZ has, “chafed at being eclipsed by a Saudi royal who U.A.E. officials believe has made some serious missteps.” Moreover, in the realm of soft power, “the Saudi purchase in 2021 of Newcastle, England’s soccer club and investment in global superstar players took place just as Manchester City—owned by a prominent member of Abu Dhabi’s ruling family—became a title winning powerhouse.”

The Saudis and Emiratis have called themselves the closest of allies, but they have had a sometimes tense relationship since even before the U.A.E. gained independence from Britain in 1971. The U.A.E.’s founding father, Sheikh Zayed al Nahyan, bristled at Saudi domination of the Arabian peninsula, and then-Saudi King Faisal refused to recognize his Persian Gulf neighbor for years, seeking leverage in various territorial disputes. In 2009, the U.A.E. scuttled plans for a common Gulf central bank over its proposed location in Riyadh. To this day, there are territorial disputes over oil-rich land between the two countries.

The rift bubbled to the surface in October last year when OPEC, the 13-nation oil-production group that has allied with Russia , decided to slash oil output; the UAE went along with the cut, but in private told U.S. officials and the media that Saudi Arabia had forced it to join the decision. Emirati frustrations reached the point where they told U.S. officials they were ready to pull out of OPEC, according to Gulf and U.S. officials. U.S. officials said they took it as a sign of Emirati anger, not a real threat. At OPEC’s last meeting, in June, the Emiratis were allowed a modest increase in their production baseline, and their energy minister emerged holding hands with his Saudi counterpart.

As Iskandar (2024) writes, “in December 2022, MBS expressed his frustrations openly, accusing UAE officials of betrayal. It is said that the Saudi de facto ruler threatened punitive measures “worse than what it did to Qatar” (regarding the Qatar boycott, see: Al-Ansari, 2021). Saudi–UAE discord has been described as a mostly “quiet conflict” as these two dominant GCC countries vie for regional dominance and engage in geoeconomic competition. Rivalry has become more pronounced latterly as both anticipate a future less dependent on oil revenues and more focused on diversified economic growth” (see, e.g., Morgan, 2020; Reisinezhad & Bushehri, 2024).

The increasing activism in Saudi and Emirati regional policies is no longer based on money and diplomacy alone, as it used to be, but also on military means. They have intervened in Bahrain in 2011, in Libya in 2011, in Iraq and Syria against ‘Daesh’ — the now very much weakened Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) — and in Yemen since March 2015 (Ragab, 2017, p. 37). Both countries are also said to be involved with the armed conflict that is ongoing in Sudan (see, e.g., Bissada, 2024; Gallopin, 2020; Mohammad, 2023; Pilling, England, & Schipani, 2023; Prendergast & Lake, 2024; Walsh, Koettl, & Schmitt, 2023).

Worth (2020), in a highly informative, longform profile piece on MBZ, writes that:

On Sept. 11, 2001, M.B.Z. was in northern Scotland, enjoying the last morning of a weeklong rabbit-hunting excursion with his friend King Abdullah II of Jordan. He said his goodbyes and boarded a private plane to London, arriving just after lunch. He hadn’t even left the plane when an Egyptian member of his entourage came running out from the terminal and climbed onboard, according to an official who was present. “New York is burning!” the man shouted. M.B.Z. had heard nothing of the day’s events, and when he did he was furious. “What are you saying?” he asked the man. “New York is the center of the world — look how vulnerable we are.” M.B.Z. tried to reach his father, but was unable to get through. He did manage to get Clarke, who was then working on counterterrorism in the White House. It was the only call Clarke took that morning from outside the government. “Carte blanche — just tell me what to do,” he recalled M.B.Z. telling him.

By the time M.B.Z. arrived back in Abu Dhabi, later that day, he knew that two Emiratis were among the 19 hijackers. The Sept. 11 attacks were a life-changing moment for M.B.Z., unmasking both the depth of the Islamist menace and the Arab world’s state of denial about it. That October, M.B.Z. told me, he listened in amazement as an Arab head of state, meeting with his father on a visit to Abu Dhabi, dismissed the attacks as an inside job involving the C.I.A. or the Mossad. After the head of state left, Zayed turned to M.B.Z., who had been there for the meeting, and asked what he thought. “Dad,” M.B.Z. recalled telling his father, “we have evidence.” That fall, the Emirati security services arrested about 200 Emiratis and about 1,600 foreigners who were planning to go to Afghanistan and join Al Qaeda, including three or four who were committed to becoming suicide bombers.

That same autumn, M.B.Z. had another conversation with his father that would affect the way he thought about political Islam. The encounter began, M.B.Z. told me, when he entered his father’s office with a momentous piece of news: The Americans were sending troops to Afghanistan. Zayed said he wanted Emirati troops to join them. M.B.Z., who was commanding the armed forces by this time, was not prepared for this. Taking an active role in the American campaign would raise sensitive issues, given that some were calling it a war against Islam. Sensing his son’s unease at the prospect of committing troops, Zayed said: “Tell me, do you think I’m doing this for Bush?” M.B.Z. said yes. “That’s 5 percent of it,” Zayed said. “Do you think I’m doing this to keep bin Laden away?” M.B.Z. nodded. “That’s another 5 percent.” M.B.Z., a little baffled, asked his father to explain. “You’ve read the Quran and the Hadith, the sayings of the Prophet,” Zayed said. “And you like them?” Of course, his son replied. Zayed then said: “Mohammed, do you think this guy bin Laden running around Afghanistan is doing what the Prophet wanted us to do?” Not at all, M.B.Z. said. His father then told him emphatically: “You’re right. Our religion is being hijacked.” M.B.Z. didn’t have to add that there was another reason to fight Al Qaeda — it was a threat to their own family’s authority.

In 1996, Osama bin Laden, the then head al-Qaeda issued his first fatwā, which declared war against the United States and demanded the expulsion of all American soldiers from the Arabian peninsula. In a second fatwā (1998), Osama bin Laden outlined his objections to American foreign policy with respect to Israel, as well as the continued presence of American troops in Saudi Arabia after the Gulf War (see: Maps of the Arabian peninsular). Osama bin Laden maintained that Muslims are obliged to attack American targets until the aggressive policies of the U.S. against Muslims were reversed. As of 1999, Bin Laden was residing in Afghanistan.

The aircraft hijackers in the September 11 attacks were 19 men affiliated with al-Qaeda. They came from four countries; 15 of them were citizens of Saudi Arabia, two were from the United Arab Emirates, one was from Egypt, and one from Lebanon.

In the aftermath of the “Arab Spring” Worth (2020) continues:

M.B.Z. had already hatched an immensely ambitious plan to reshape the region’s future. He would soon enlist as an ally Mohammed bin Salman, the young Saudi crown prince known as M.B.S., who in many ways is M.B.Z.’s protégé. Together, they helped the Egyptian military depose that country’s elected Islamist president in 2013. In Libya in 2015, M.B.Z. stepped into the civil war, defying a United Nations embargo and American diplomats. He fought the Shabab militia in Somalia, leveraging his country’s commercial ports to become a power broker in the Horn of Africa. He joined the Saudi war in Yemen to battle the Iran-backed Houthi militia. All of this was aimed at thwarting what he saw as a looming Islamist menace.

M.B.Z. makes little distinction among Islamist groups, insisting that they all share the same goal: some version of a caliphate with the Quran in place of a constitution. He seems to believe that the Middle East’s only choices are a more repressive order or a total catastrophe. It is a Hobbesian forecast, and doubtless a self-serving one. But the experience of the past few years has led some veteran observers to respect M.B.Z.’s intuitions about the dangers of political Islam writ large. “I was sceptical at first,” says Brett McGurk, a former United States official who spent years working in the Middle East for three administrations and knows M.B.Z. well. “It seemed extreme. But I’ve come to the conclusion that he was often more right than wrong.”

M.B.Z. has put many of his resources into what could be called a counter jihad, and they are formidable. Despite his country’s small size (there are fewer than a million Emirati citizens), he oversees more than $1.3 trillion in sovereign wealth funds, and commands a military that is better equipped and trained than any in the region apart from Israel. On the domestic front, he has cracked down hard on the Brotherhood and built a hypermodern surveillance state where everyone is monitored.

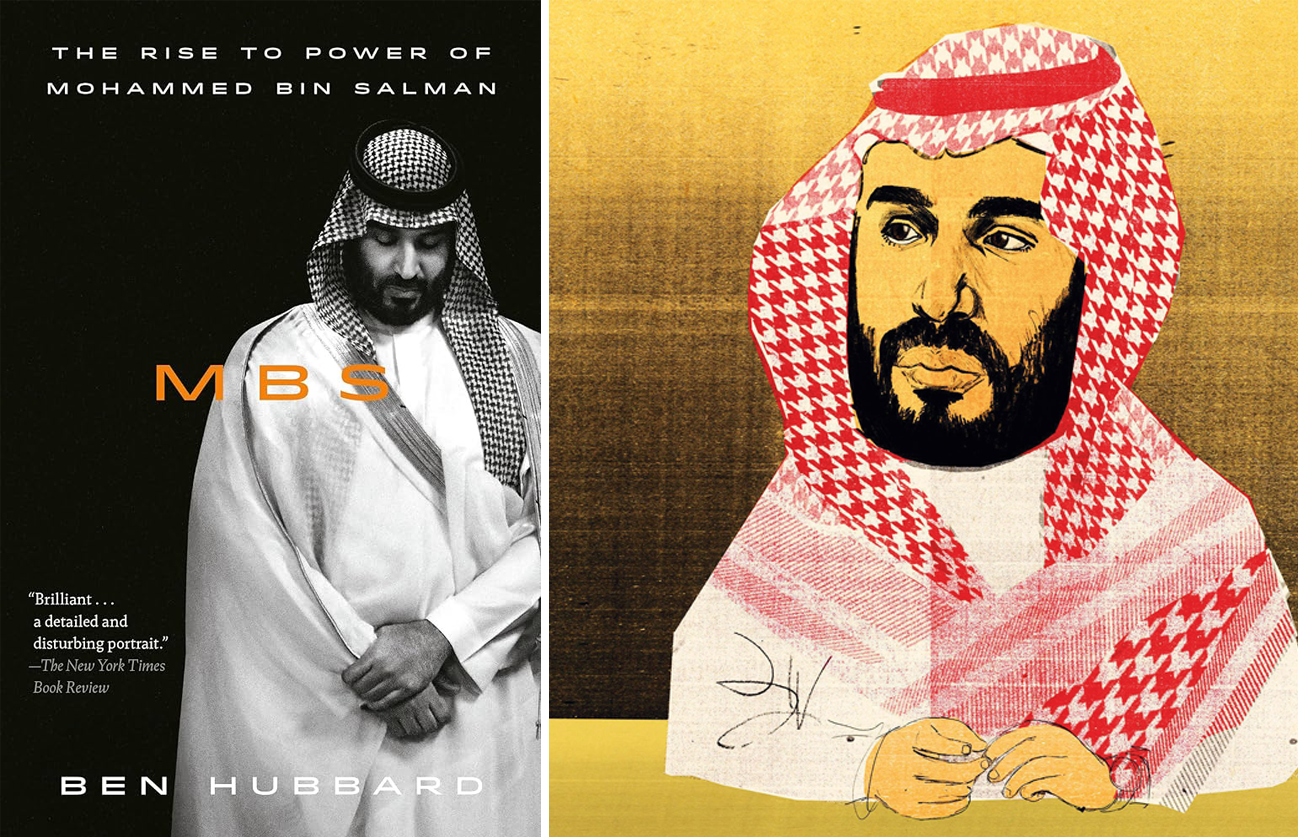

In a review of Ben Hubbard’s 2020 book, MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed Bin Salman, Ghattas writes in the New Statesman magazine (2020) that:

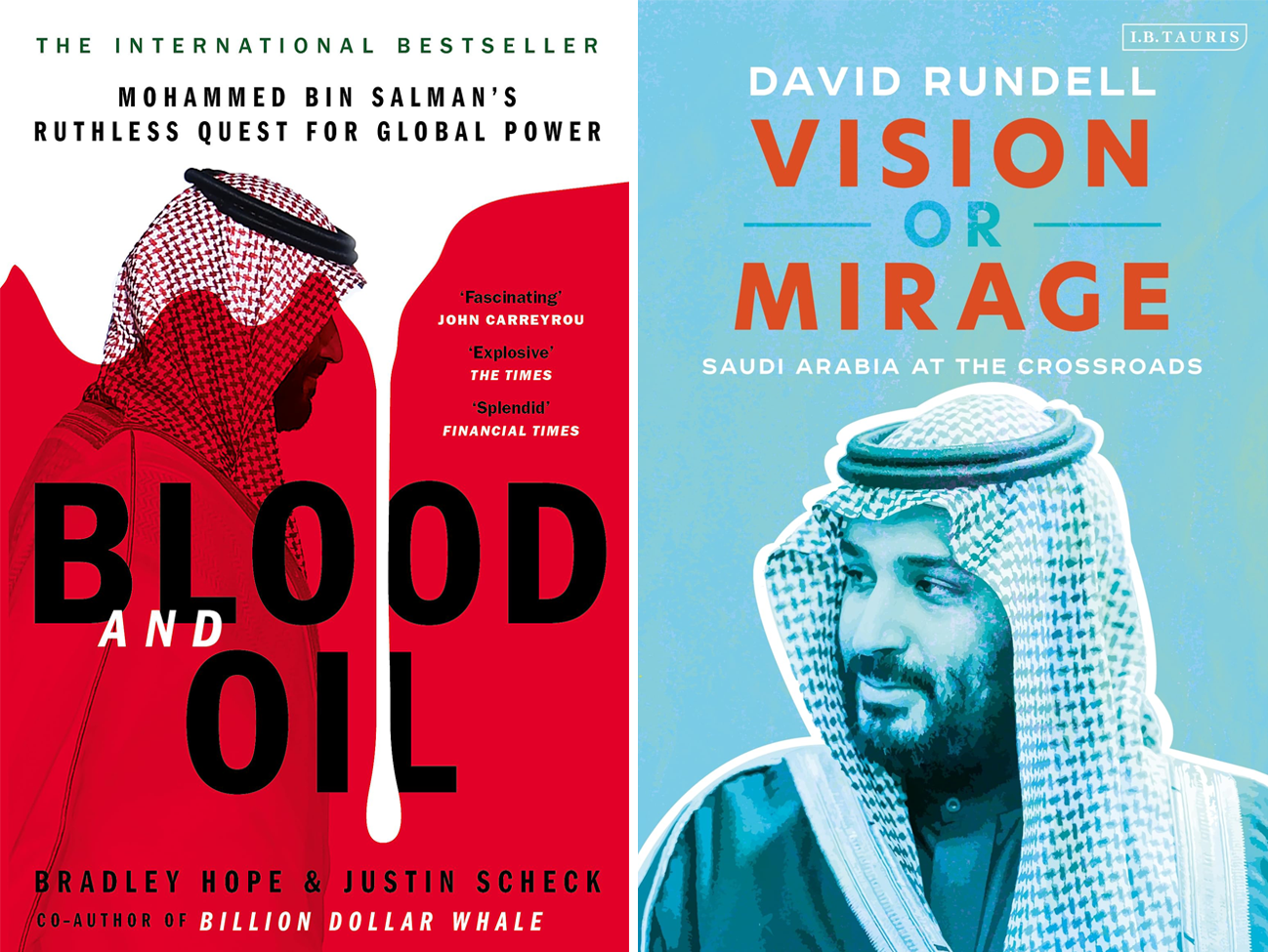

MBS’s grandiose reform plans are now under intense pressure. His ambition, laid out in Vision 2030 – a programme to lessen the country’s reliance on oil and bring about a more “vibrant” society – was the only reason the young prince became a darling of the West soon after he was catapulted on to the world stage in 2015. He did not deliver on his promise that by 2020 the kingdom would be able to live without oil. There are no revelations in MBS but Hubbard, Beirut bureau chief for the New York Times, who has spent more than a dozen years reporting from the region, delivers a compelling tale for a wide audience – more reportage than narrative, more anecdotes than deep analysis. In doing so, he provides non-experts with an accessible biography that does not stray into sensationalism but helps make sense of all the recent headlines around the impulsive, and one could argue, dangerous, young prince. MBS did not give an interview for the book and Hubbard is upfront about the gaps that remain in our understanding of a man who until just a few years ago did not seem destined to be more than one among thousands of princes in the House of Saud. As he writes:

Much still remains unclear about how MBS spent his twenties, largely because he did so little that drew attention at the time and because so much effort would later go into retroactively polishing his reputation. But what is clear is everything MBS did not do before he burst on to the scene in 2015. He never ran a company that made a mark. He never acquired military experience. He never studied at a foreign university. He never mastered, or even become functional in, a foreign language. He never spent significant time in the United States, Europe, or elsewhere in the West. And yet, this man, though still only crown prince, launched a devastating war in Yemen in 2015, played a high-risk gambit in the global oil market and chatted away on WhatsApp with another inexperienced princeling, Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law, discussing policies with consequences that reverberate around the world, including the stand-off with Iran.

MBS seemed to revel in the role of disrupter. In 2017 he went on a crusade against corruption, rounding up dozens if not hundreds of princes, businessmen and others in the Ritz Carlton hotel, stripping them of their fortunes and provoking an economic earthquake in the kingdom. But while there was indeed mass corruption in Saudi Arabia, Hubbard argues that it was in an environment “created by the royal family” and those princes who were still on MBS’s good side could continue to profit. Just like MBS himself, who appeared not to see the contradiction between what he preached and his own spending habits, buying a $300m house, a super-yacht and, reportedly, Leonardo da Vinci’s painting Salvator Mundi for $450m. The prince’s excesses and rough edges were dismissed by those he charmed, from Silicon Valley to Washington, DC. He dangled the prospect of huge deals and investment opportunities in the kingdom, of cities rising in the desert where “scientists could modify the human genome to make people smarter and stronger. Mechanical dinosaurs could populate a Jurassic Park-like attraction… A beach would feature glow-in-the-dark sand.”

Here, finally, was a young man with vision who could bring the kingdom into the 21st c. And in many ways, MBS did go where no other royal had gone. He defanged the religious police and brought music, cinema and theatre to the austere kingdom where they had been deemed a sin for centuries. He understood this was essential to defuse the time bomb of a very young and very bored, frustrated population. He also reversed the ban on women driving – while jailing the women who had campaigned for the right to drive lest anyone get any ideas about the power of activism in an absolute monarchy.

In an interesting profile piece on MBS, Pelham (2022) writes:

At first glance the 36-year-old prince looks like the ruler many young Saudis had been waiting for, closer in age to his people than any previous king – 70 per cent of the Saudi population is under 30. The millennial autocrat is said to be fanatical about the video game “Call of Duty”: he blasts through the inertia and privileges of the mosque and royal court as though he were fighting virtual opponents on screen. His restless impatience and disdain for convention have helped him push through reforms that many thought wouldn’t happen for generations. The most visible transformation of Saudi Arabia is the presence of women in public where once they were either absent or closely guarded by their husband or father. There are other changes, too. Previously, the kingdom offered few diversions besides praying at the mosque; today you can watch Justin Bieber in concert, sing karaoke or go to a Formula 1 race. A few months ago I even went to a rave in a hotel. Saudis and foreigners danced barefoot on the sand until dawn, a couple kissed, women stripped down to tank tops and fruit juice laced with alcohol was served at an open bar. But embracing Western consumer culture doesn’t mean embracing Western democratic values: it can as easily support a distinctively modern, surveillance state. On my recent trips to Saudi Arabia, people from all levels of society seemed terrified about being overheard voicing disrespect or criticism, something I’d never seen there before. “I’ve survived four kings,” said a veteran analyst who refused to speculate about why much of Jeddah, the country’s second-largest city, is being bulldozed: “Let me survive a fifth.”

In another very in-depth profile piece on MBS, Wood (2022) writes:

Even MBS’s critics concede that he has roused the country from an economic and social slumber. In 2016, he unveiled a plan, known as Vision 2030, to convert Saudi Arabia from—allow me to be blunt—one of the world’s weirdest countries into a place that could plausibly be called normal. It is now open to visitors and investment, and lets its citizens partake in ordinary acts of recreation and even certain vices. The crown prince has legalized cinemas and concerts, and invited notably raw hip-hop artists to perform. He has allowed women to drive and to dress as freely as they can in dens of sin like Dubai and Bahrain. He has curtailed the role of reactionary clergy and all but abolished the religious police.

Before the meetings, I asked one of MBS’s advisers if there were any questions I could ask his boss that he himself could not. “None,” he answered, without pausing—“and that is what makes him different from every crown prince who has come before him.” I was told he derives energy from being challenged. At the outset of both conversations, MBS said he was saddened that the pandemic precluded giving us hugs. He apologized that we all had to wear masks. (Each meeting was attended by multiple, mainly silent princes wearing identical white robes and masks, leaving us unsure, to this day, who exactly was present.)

The crown prince left his tunic unbuttoned at the collar, in a casual style now favored by young Saudi men, and he gave relaxed, non-psychopathic answers to questions about his personal habits. He tries to limit his Twitter use. He eats breakfast every day with his kids. For fun, he watches TV, avoiding shows, like House of Cards, that remind him of work. Instead, he said without apparent irony, he prefers to watch series that help him escape the reality of his job, such as Game of Thrones.

Vision 2030 made modernisation easier to observe now than it would have been just a few years ago. Until October 2019, tourist visas to Saudi Arabia did not exist. Then the Saudis realised that to attract crowds to the concerts they had legalised, they’d need to let in visitors. Overnight, a visa to Saudi Arabia went from one of the hardest in the world to get to one of the easiest. In minutes I had one valid for a whole year.

Yet after spending hours in MBS’s company, and in the company of his allies and enemies, I was convinced that neutering the clergy was not just symbolic. He was fighting them avidly, and personally. “The kings have historically stayed away from religion,” Bernard Haykel, a scholar of Islamic law at Princeton and an acquaintance of MBS’s, told me. Outsourcing theology and religious law to the big beards was both an expedient and a necessity, because no ruler had any training in religious law, or indeed a beard of any significant size. By contrast, MBS has a law degree from King Saud University and flaunts his knowledge and dominance over the clerics. “He’s probably the only leader in the Arab world who knows anything about Islamic epistemology and jurisprudence,” Haykel told me.

That being said, the conservatism in Saudi society has not gone away, rather in many instances, it has just undergone a “costume change;” as Wood (2022) continues:

These lingering manifestations of intolerance illustrate what MBS’s critics say is his ultimate error: Even a crown prince can’t change a culture by fiat.

Belated realisation of this error might be behind the grandest and most improbable of his projects. If existing cities resist your orders, just build a new one programmed to do your bidding from the start. In October 2017, MBS decreed a city in a mostly uninhabited area on the Gulf of Aqaba, adjacent to Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, the southwestern edge of Jordan, and the Israeli resort town Eilat. The city is called Neom, from a violent collision between the Greek word neos (“new”) and the Arabic mustaqbal (“future”).

At present, little exists but an encampment for the employees of the Neom project (see: “On the giga-scale”), a small area of tract housing. Regular buses take them to shop in the nearest city, Tabuk, which is itself a city only by the standards of the vacant, rock-strewn desert nearby. (If you recall the early scenes of Lawrence of Arabia, when a lonely camel-borne Peter O’Toole sings “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo” to the echoes of a sandstone canyon, then you know the spot.) The ambitions for this settlement are vast. Neom’s administrators say they expect it to attract billions of dollars in investment and millions of residents, both Saudi and foreign, within 10 to 20 years. Dubai grew at a similar pace in the 1990s and 2000s. MBS said Neom is “not a copy of anything elsewhere,” not a xerox of Dubai. But it has more in common with the great globalised mainstream than with anything in the history of a country that, until recently, was remarkably successful at walling off its traditional culture from the blandishments of modernity.

This is how the profile piece, penned by Robert F. Worth in 2020, on MBZ ends; it is telling indeed:

One morning in June, I got a taxi from my hotel to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, M.B.Z.’s madly ambitious, billion-dollar monument to “art and civilization.” It was unbearably hot and humid out, and as we drove past the corniche — a beautifully landscaped mile-long stretch of waterfront — I didn’t see a single human being. As we crossed the bridge onto Saadiyat Island, I could see the museum looming in the distance like a vast metallic tortoise. Its steel dome, which is as heavy as the Eiffel Tower, is a weave of strands designed to act like a palm grove, allowing tiny shards of sunlight onto the grounds below. … Inside, I goggled alongside the tourists at classic works of Western art sitting alongside Chinese and Indian and Arab masterpieces. The museum’s guiding concept reflects the U.A.E.’s own multicultural ethos, a mash-up of global high culture. It has been derided by some critics, including many in France, as a lavish purchase of a European brand for the benefit of a global leisure class. But M.B.Z.’s main goal for the museum, one of his advisers told me, was to educate the local population, not attract tourists.

As I strolled past a Roman sculpture, a group of Emirati schoolchildren in green shirts trickled in and sat on the floor around me. After a few minutes of sketching, their teachers led them toward the Universal Religions gallery, the museum’s centrepiece. I followed behind and listened as one of the teachers led a Q. and A. “You all know about the Quran,” he said. “But who can tell me what the Christian holy book is?” Several children shouted the answer. “Very good! What about the Jewish holy book? And for Hindus?” More high-pitched answers. At last came the clincher. “Sheikh Zayed wanted this to be a universal museum, and he had the idea to put all the holy books in one place, so people could see what their religions had in common, and perhaps that way they’d be a bit nicer to each other.” As the children got up and filed into the next room, it struck me that the teacher’s lecture contained a revealing false note. Sheikh Zayed wasn’t the one who conjured up this museum, with its grand ambition to smash Islamic certainties and turn Bedouins into citizens of the world. M.B.Z. was hiding in his father’s shadow, absent and omnipotent at the same time.

More generally, all Arabian Gulf countries adopted monarchy as a political system, what emerged was a tribal dynastic monarchy in that the extended families were included as part of an extended royal family. Indeed, this characteristic distinguishes these monarchies of the Gulf region from the majority of other monarchical systems that have existed internationally. Wright (2020, p. 352) points out that, “the pattern of including members of the ruling family as ministers in the cabinet was an important indicator of the distribution of power and authority.” According to Al-Rasheed (2020, p. 337), “the long-term prospects of the contradictory strategy of reform and repression are bleak” as this will result in a spiral of “violence and retaliation, alienating the youth that the regime supposedly wants to empower.”

Further reading

Surveillance / internet control

In 2017, the Saudi government urged citizens to report subversive comments spotted on social media via a phone app which was promptly denounced by Saudi dissidents and U.S.-based Human Rights Watch as “Orwellian” (Reuters, 2017). As reported by Mazzetti and Hubbard (2019) , MBS had authorised “a secret campaign to silence dissenters—which “included the surveillance, kidnapping, detention and torture of Saudi citizens” — see too: Bing and Schectman (2019b) and Deibert (2023).

Over the last five years, the UK has sold over £75 million ($103mn) worth of spyware, wiretaps, and telecom interception equipment to spy on dissidents, to over 17 countries including Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain. Further, in 2020 alone, the UK has authorised £1.88 billion ($2.6bn) worth of arms sales to the Saudi-led coalition in war-torn Yemen (TNT World, 2021).

In 2023, social media users were arrested or fined for their online posts (Freedom House, 2023). Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are amongst the most connected countries in the world, this gives the country a particularly high score for this component of their Internet Freedom score — masking, to an extent, quite how poorly they sources in other regards. In terms of internet access in Saudi Arabia, users “face extensive censorship and surveillance, which limits their ability to access diverse content or speak freely online” (Freedom House, 2023). While internet access is widespread and most social media and communications platforms are available, authorities routinely block websites, remove content, and deliberately manipulate online information to positively portray the government and its policies. Criticism of the government is not tolerated and the threat of harassment or prosecution under broadly worded laws forces many Saudi social media users to self-censor. “The regime relies on extensive surveillance, the criminalisation of dissent, appeals to sectarianism and ethnicity, and public spending supported by oil revenues to maintain power. In 2020, Saudi authorities “requested that platforms such as Netflix and YouTube remove online content deemed “inappropriate,” and threatened legal action should the platforms not comply with the requests” (Freedom House, 2023). It was established that the government has recruited Saudi-based Wikipedia administrators to deliberately manipulate information on pages related to the country (Freedom House, 2023). Regarding the UAE. internet freedom is significantly restricted. Online censorship is rampant, and the online media environment lacks diversity. Government surveillance of online activists and journalists is pervasive and has forced internet users to extensively self-censor. Authorities and government supporters continue to use increasingly sophisticated technology to spread disinformation that advances pro-UAE domestic and international narratives on social media.

Leading efforts to pre-emptively stifle possible threats to regime security have been Saudi Arabia and the UAE. These two countries have been mobilising cutting-edge surveillance technology and foreign expertise to suppress dissent within their borders and amongst their citizens abroad (Bing & Schectman, 2019a, 2019b; Uniacke, 2021, p. 980). Uniacke (2021) argues that most of the Gulf monarchies seek to depoliticise and de-civilise online debate through promoting regime-friendly narratives that expose, criticise, crowd-out, delegitimise and ultimately deter political dissidents.” “Saudi security officials sought to galvanise regime supporters into policing the online space, adding an extra layer of surveillance capability to their already muscular communications interception technology. The public prosecutor reminded social media informants – otherwise known as ‘electronic flies’ – that the Kingdom’s laws saw terrorism as ‘endangering national unity . . . and harming the state’s reputation or status … by such an interpretation, voicing political opposition beyond the parameters of acceptable debate set by the regime is ultimately equated with extremism and terrorism” Uniacke (2021, pp. 979-980). Simultaneously, they aim to ‘de-civilise’ civil society, encouraging intolerance for pluralistic political arguments beyond the state narrative to engineer an online quasi-debate with clearly defined political and cultural limitations to easily identify dissenters and buttress regime security (Uniacke, 2021, p. 980).

As Uniacke (2021, p. 981) argues, the forming of a specific, thematically defined ‘free’ space for online debate has become a function of digital authoritarianism in itself. … Exacerbating this online opinion engineering is the coercive potential of commercial big data, easily repurposed for political intelligence on citizens’ opinions and habits by authoritarian and democratic governments alike.

Indeed, the Saudi and Emirati regimes show a demonstrable intolerance for any dissenting political narratives that may be considered expressions of freedom, an independent civil society or reform even within the prevailing system that contradicts the national ‘Vision.’ Instead, they are attempting, with varying degrees of execution of success, to galvanise the citizenry to perform economically while simultaneously suppressing politically-minded civil society. … “if adult citizens take on new jobs, responsibilities, and lifestyles willingly, then ruling elites do not have to undertake painful structural reforms – and risk their own necks, politically, to make them do so” (Uniacke, 2021, p. 985).The Saudi regime’s instrumentalisation of the online public sphere relies on leveraging artificial ‘public opinion’ by both mechanical and organisational means in order to galvanize organic reactions that directly or indirectly promote regime policy. The debate is intentionally stripped of its civil dimension; intolerance for pluralism and an atmosphere of ‘fear and loathing’ prevail by way in an interactive process of coercion, drawing citizens into the parameters of regime-friendly debate and thus depoliticising their engagement with the online space (see too: Pan & Siegel, 2020).

References

Al-Ansari, M. M. H. (2021). The Unbridgeable Gulf: Applying Bennett’s Model of Analysis to the 2017 Gulf Crisis. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern studies, 23(3), 502–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2021.1888252

Al-Rasheed, M. (2020). Brute Force and Hollow Reforms in Saudi Arabia. Current history, 119(821), 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2020.119.821.331

BBC. (2024). The Kingdom: The World’s Most Powerful Prince. [Television documentary]. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/m001zprm/the-kingdom-the-worlds-most-powerful-prince

Bing, C., & Schectman, J. (2019a). The Karma Hack – UAE used cyber superweapon to spy on iPhones of foes. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-spying-karma/

Bing, C., & Schectman, J. (2019b). Project Raven – Inside the UAE’s secret hacking team of American mercenaries. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-spying-raven/

Bissada, A. (2024, May 20). Gulf rivals UAE and Saudi Arabia vie for power while stoking Sudan’s civil war. The Africa Report. https://www.theafricareport.com/348154/gulf-rivals-uae-and-saudi-arabia-vie-for-power-while-stoking-sudans-civil-war/

Deibert, R. J. (2023). The Autocrat in Your iPhone: How Mercenary Spyware Threatens Democracy. Foreign Affairs, 102(1), 72–88. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/autocrat-in-your-iphone-mercenary-spyware-ronald-deibert

Dunne, C. W. (2023, July 6). The UAE-Saudi Arabia Rivalry Becomes a Rift. Arab Center. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-uae-saudi-arabia-rivalry-becomes-a-rift/

England, A. (2023, August 23). ‘Bridges with everyone’: how Saudi Arabia and UAE are positioning themselves for power. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/3889c33d-4830-407c-a3f6-f9e3cfaaa35f

Freedom House. (2023). Freedom on the Net, 2023. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/FOTN2023Final.pdf

Gallopin, J. B. (2020, June 20). The Great Game of the UAE and Saudi Arabia in Sudan. The Project on Middle East Political Science. https://pomeps.org/the-great-game-of-the-uae-and-saudi-arabia-in-sudan

Ghattas, K. (2020, May 8). Disrupting the desert kingdom. New Statesman, 149(5519), 48–49. https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2020/05/mbs-rise-power-mohammed-bin-salam-crown-prince-saudi-arabia-ben-hubbard-review

Harris, S., Said, S., & Crow, K. (2017, December 8). Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Identified as Buyer of Record-Breaking da Vinci. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabias-crown-prince-identified-as-buyer-of-record-breaking-da-vinci-1512674099

Hope, B., & Scheck, J. (2020). Blood and Oil: Mohammed Bin Salman’s Ruthless Quest for Global Power. Hachette Books.

Hubbard, B. (2020). MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed Bin Salman. Random House.

Iskandar, M. (2024, April 26). Troubled waters: Al-Yasat dispute reignites Saudi–Emirati contest. The Cradle. https://thecradle.co/articles-id/24591

Mazzetti, M., & Hubbard, B. (2019, March 18). Saudi Prince Ran Brutal Campaign To Stifle Dissent. The New York times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/17/world/middleeast/khashoggi-crown-prince-saudi.html

Mohammad, T. (2023). How Sudan Became a Saudi-UAE Proxy War. Foreign Policy, 1(250), 22–24. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/07/12/sudan-conflict-saudi-arabia-uae-gulf-burhan-hemeti-rsf/

Morgan, T. (2020, June 28). The complex relationship between Saudi Arabia and UAE that could soon shape the Premier League. The Daily Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/football/2020/06/28/special-report-complex-relationship-saudi-arabia-uae-could-soon/

Pan, J., & Siegel, A. A. (2020). How Saudi Crackdowns Fail to Silence Online Dissent. The American political science review, 114(1), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000650

PBS. (2019). The Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia. [Television documentary]. Arlington, Virginia: Public Broadcasting Service. https://www.pbs.org/video/crown-prince-saudi-arabia-1jt2ey/

Pelham, N. (2022, July 28). MBS: Despot in the desert. The Economist, 444(9307). https://www.economist.com/1843/2022/07/28/mbs-despot-in-the-desert

Pilling, D., England, A., & Schipani, A. (2023, April 19). Risk of regional powers picking sides raises stakes in battle for Sudan. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/228f929d-a73f-4bb3-83b0-70707ee48348

Prendergast, J., & Lake, A. (2024). The UAE’s secret war in Sudan. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/sudan/uaes-secret-war-sudan

Ragab, E. (2017). Beyond Money and Diplomacy: Regional Policies of Saudi Arabia and UAE after the Arab Spring. The International Spectator, 52(2), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2017.1309101

Reisinezhad, A., & Bushehri, M. (2024, January 25). The Hidden Rivalry of Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/25/the-hidden-rivalry-of-saudi-arabia-and-the-uae/

Reuters. (2017, September 13). Saudi calls for social media informants decried as ‘Orwellian’. Reuters. https://au.news.yahoo.com/saudis-urged-report-other-apos-124148016.html

Rundell, D. (2020). Vision or Mirage: Saudi Arabia at the Crossroads. Bloomsbury Academic.

Said, S., Nissenbaum, D., Kalin, S., & Al Batati, S. (2023, July 18). The Best of Frenemies: Saudi Crown Prince Clashes With U.A.E. President. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/frenemies-saudi-crown-prince-mbs-clashes-uae-president-mbz-c500f9b1

TRT World. (2021, May 8). Gulf ownership of UK assets raise questions over undue influence. TRT World. https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/gulf-ownership-of-uk-assets-raise-questions-over-undue-influence-45908

Uniacke, R. (2021). Authoritarianism in the information age: state branding, depoliticizing and ‘de-civilizing’ of online civil society in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 48(5), 979–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2020.1737916

Walsh, D., Koettl, C., & Schmitt, E. (2023, September 30). While Talking Peace, U.A.E. Fuels Sudan Fight. The New York times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/29/world/africa/sudan-war-united-arab-emirates-chad.html

Wood, G. (2022, March 3). Absolute Power. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/04/mohammed-bin-salman-saudi-arabia-palace-interview/622822/

Worth, R. F. (2020, January 9). The M.B.Z. Moment. New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/09/magazine/united-arab-emirates-mohammed-bin-zayed.html

Wright, S. (2020). Political absolutism in the Gulf monarchies. In M. Kamrava (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of Persian Gulf Politics (pp. 346–356). Taylor & Francis Group.