Socio-economic insight

| i | This is the website of Dr Emilie J. Rutledge who, with almost two decades’ worth of experience in managing, designing and delivering university-level economics courses, is currently Head of the Economics Department at The Open University.

erutledge.com  Dr Emilie J. Rutledge Emilie has published over 20 peer-reviewed papers and is the author of “Monetary Union in the Gulf.” Her current research focus is on employability, the feasibility of universal basic incomes and, the oil-rich Arabian Gulf’s economic diversification and labour market reform strategies. On an ad hoc basis, Emilie provides consultancy on developing interactive university courses, alongside analytical insight on the political-economy of the Arabian Gulf. |

The Arabian Gulf

Since the late 1990s, the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC), which comprises Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (a.k.a., “the Arabian Gulf” countries of the Arabian peninsula), has undergone rapid socioeconomic change.[1] From 1998, the six-country economic bloc’s real GDP has expanded by an annual average of around five per cent. Over this period, the population has risen from 28 to 59 million (as of 2025). What makes the region unique demographically-speaking, is that of the current population, only 43 per cent are Gulf citizens (Khaleejis meaning: “people of the gulf”). Of the 25 million Khaleejis, almost four-fifths are Saudi nationals (see: Arabian Gulf data). At the other end of the spectrum, there are only several hundred thousand Qatari citizens and, a million at most Emiratis.

With the exception of Oman and Saudi Arabia, the citizenries of all Gulf countries are in the minority (relative to their respective pools of expatriate residents) and, as a consequence, rely heavily on non-national labour to carry out all manner of work. In Qatar and the UAE, nationals only make up a small fraction of their respective workforces (five and nine per cent respectively; and in terms of the real private sector comprise only a few percentage points at most).

The unprecedented economic boom, that has been occurring for much of the period since the turn of the millennium (a short, sharp and spectacular real-estate bubble bust and “Arab Spring” ripples aside), has focused world attention on the region’s economies in a new light. No longer are these countries viewed solely as quiet and unobtrusive exporters of oil and gas. Increasingly, they are seen as investment destinations, where audacious ‘giga-projects’ manifest; as ‘tax-free’ escapes and, as places that harbour global brands such as Al-Jazeera and places that host global events such as the FIFA World Cup and the 2020 World EXPO. In 2030, Saudi Arabia is penciled in to host Expo 2030 and then, in 2034 the FIFA World Cup. Further, in the international political-economy arena, several Gulf countries are seeking to become global players, be it Qatar’s ever-patient and pivotal role as a place for international powers to coalesce and seek to alter interactable geopolitical issues (e.g., Palestine) or Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s more bellicose and interventionist foreign policy stances. With major infrastructural projects well underway, a booming tourism sector and several financial and transportation hubs with pretentions to become global firsts, the region can no longer be considered, as it once was by some, either as a bastion of reactionary conservative procrastination or, as being determined solely by a collective ‘Rentier mentality.’

Dubai was not even on the 1965 map (shown below) but, come the 2016 DK Atlas map, it was the only Middle East and North African (MENA) country to be granted the privilege of having a stand-out city map. Somewhat prophetically, an adverting campaign by a government-owned construction company, Nakheel Properties, pasted on billboards along Dubai’s Sheikh Zayed arterial road in the early 2000s, read something like: “Dubai puts ‘The World’ on the map; The World puts Dubai on the map.” Indeed, ‘The World’ is observable on the fourth map below and these dredged islands can be seen from space — as can China’s Great Wall (just like the developers in Dubai had planned for them to be).

Oil’s ‘blessings’ & the American dollar standard

📕 “Political maps of Arabia” →

The economic and political impact of the bloc’s huge Sovereign Wealth Funds, actual (e.g., gold bullion and stakes in advanced economy companies) and potential (i.e., their vast state-owned reserves of oil and gas that remain untapped under the seas of dunes and tepid gulf waters) cannot be discounted either. Long gone are the days that the bulk of this surplus oil-rent would sit idly by (passively so) in U.K. Gilts or U.S. T-bonds; it is now also being used to acquire overseas assets and land (be that agricultural, for playing football on, coming with mines and mining rights, or that suited to building and operating containership ports on) and underwrite, if not outright fund, some of the Gulf’s most eye-catching giga-projects. On a per national-capita basis, the region harbours the largest SWFs globally (see: Arabian Gulf data). Add to that SWF capital, the aforementioned economically extractable proven reserves of oil and gas (which according to current production-to-reserve ratios mean that there’ll be oil and gas on tap for several generations to come) and, the Gulf’s sovereign wealth is considerably more astronomical than suggested by organisations that amass and rank such metrics on a country, by country basis. It may very well be argued that Qataris are by far and away the richest in per capita PPP GDP terms globally. Most, if not all, international rankings institutions do not delineate between nationals (i.e., Qataris) and the country’s large pool of temporary “guest workers” (i.e., non-nationals) when compiling their annual league tables, based on IMF datasets, masking just how rich Qatari nationals actually are. Measured this way, Emiratis and then Kuwaiti citizens are in second and third places globally.

Three of the six countries—Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE—have significant per-national capita revenues from oil and gas and, have some of the world’s highest per capita incomes (especially so when non-national labour is factored out—of utility when assessing relative national sovereign wealth endowments). Bahrain and Oman have very limited hydrocarbon reserves in comparison. Indeed, for years now, Bahrain has been largely reliant on the ‘benevolence’ of Saudi Arabia (a generosity driven by Saudi geo-strategic concerns). Bahrain produced around 200,000 barrels of oil per day in 2024 and for Oman, production was around 1,000,000 barrels per day. Saudi Arabia is something of an outlier. It does not fit well with the first three or the second two. While Saudi Arabia has by far the largest ‘easily extractable’ oil reserves globally (over 17 per cent of the world’s total) and is the biggest ‘exporter’ of oil in the world by quite some margin (ten million plus barrels per day), it has a far larger citizenry, distributed across a far large land mass, with which to distribute this resource-wealth amongst.

All that being said, the six countries, alongside their shared traditions, culture, language and confession[2] are nevertheless very much defined by oil and, the ways in which imperial powers facilitated, promoted and have long sought to influence the extraction and exportation of hydrocarbons (see: “Shadow Wars”) and control and direct the oil-rent that the Gulf generates. And despite the differences in terms landmass, national populations and per national capita resource-wealth (see: Arabian Gulf data), all six countries have a similar social contract, generally referred to as the region’s “Ruling bargain” which remains stubbornly intractable, despite the growing acceptance that it has and is, adversely impacting on labour market productivity and sustainable economic diversification.

Allocating oil-rent (“resource wealth” matters)

📕 “The Arabian Gulf Social Contract” →

📕 “Arabian Gulf sovereign wealth” →

Consultancy

Academic

Services to academia are twofold. First, support can be given with the design & management of credit-bearing university courses focused on the Arabian Gulf. Courses can be tailored to both undergraduate (e.g., introductory ones focusing on the economies of the Arabian Gulf in the global context) and postgraduate studies (i.e., MBAs and DBAs) where the focus tends to be on research methods, ethics and academic document production skills. The second form of assistance offered is with academic writing itself. This entails the editing and proof reading of documents in their pre-publication stages.

Analytical

Research insight on the Arabian Gulf’s economic diversification strategies, the region’s labour market dynamics and the political-economy ramifications of resource wealth and oil-rent allocation. Previous clients include:

Country Profiles

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bahrain

The Kingdom of Bahrain, is an island country situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an additional 33 artificial islands, centered on Bahrain Island which makes up around 83 per cent of the country’s landmass. Bahrain is situated between Qatar and the northeastern coast of Saudi Arabia, to which it is connected by the King Fahd Causeway.[3]

Map

Of the Bahrain’s 1.58 million population in 2024, 727,000 were Bahraini nationals (less than half; some 46 per cent). According to the EIU’s Democracy Index, Bahrain’s ranking is 139th (from 167 economies) and thus Bahrain is placed within the “authoritarian” regime category.

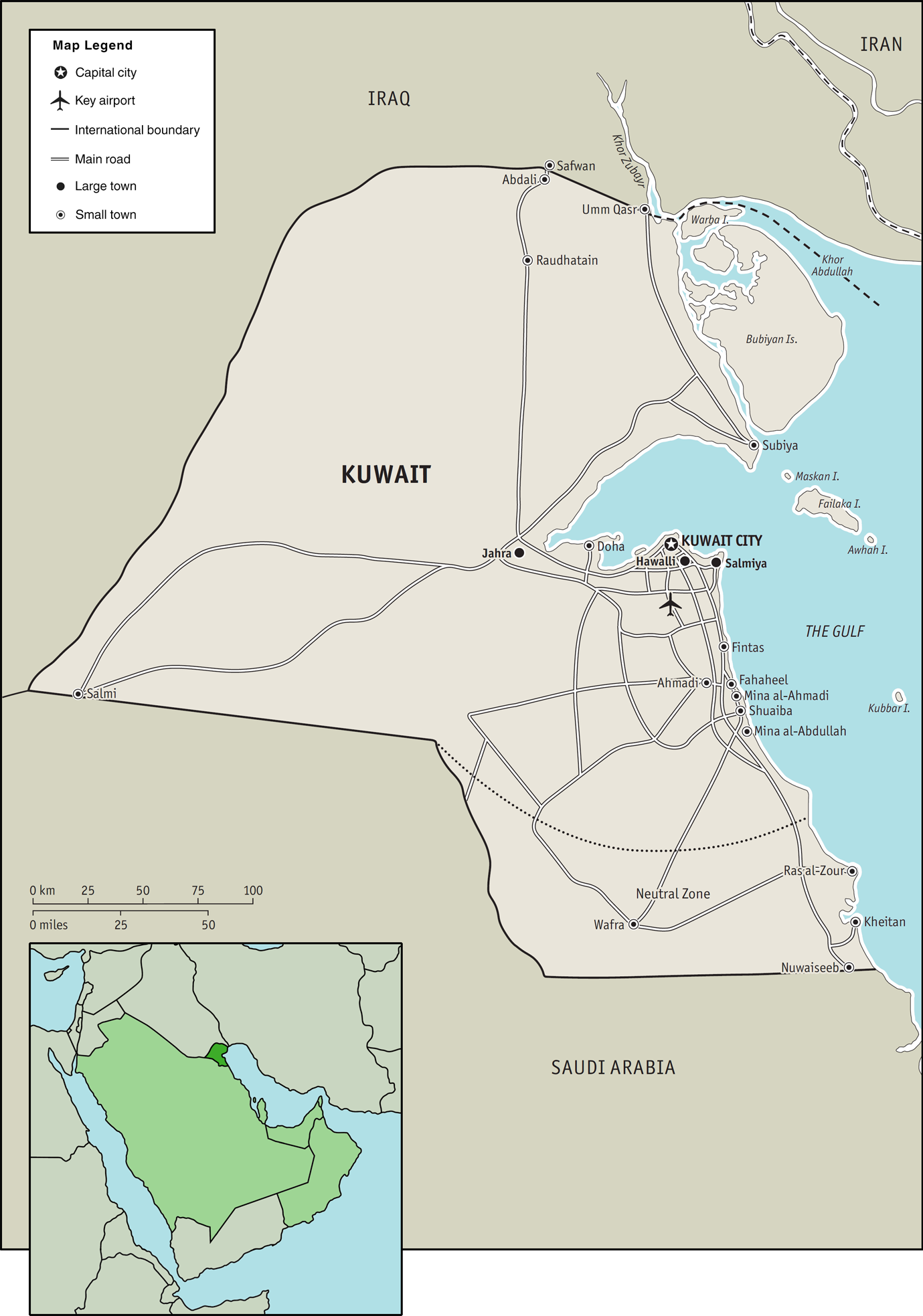

Kuwait

Kuwait is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the north and Saudi Arabia to the south. With a coastline of approximately 311 miles, Kuwait also shares a maritime border with Iran.

Map

Most of Kuwait’s population reside in the urban agglomeration of Kuwait City, the capital city. As of 2024, had a population of 4.91 million, of which 1.54 million were Kuwaiti citizens; the remaining 3.36 million were foreign nationals from a multitude of countries.

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2023 Democracy Index ranks Kuwait 114th out of 167 countries and territories, a worsening of three places compared with the 2022 index (EIU, 2024). According to the UK think-tank, Kuwait’s score has deteriorated to 3.50 out of 10, from 3.83 in 2022, “driven primarily by a sharp fall in the political participation score.” Kuwait then is categorised as an “authoritarian” regime as are all other of its Arabian Gulf neighbours. That being said, the EIU do state that “Kuwait has a more open polity than most of its fellow GCC states, and ranks the highest among them as a result.”

Oman

The Sultanate of Oman is on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. The coast faces the Arabian Sea on the southeast, and the Gulf of Oman on the northeast It has a number of smallish exclaves within the United Arab Emirate’s land borders. The capital and largest city is Muscat.

Map

Of Oman’s total population of 5.2 million, just over half are Omani citizens (2.9 million, 57 per cent). Oman’s overall score in EIU’s 2023 Democracy Index was 3.12 (out of ten) in 2023 ranking it 119th out of 167 economies. Oman’s score remains around the median for GCC countries, below Qatar’s and Kuwait’s but above those of the UAE, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. The EIU classify it as remains classified as an “authoritarian.”

Qatar

Qatar is a peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula; it shares its sole land border with Saudi Arabia to the south. The capital is Doha, home to over 80 per cent of the country’s inhabitants. Qatar has one of the highest levels of GDP per head in the world, and the highest in the GCC.

Map

The population of Qatar was 2.8 million in early 2025, although only 348,000 of these individuals are Qatari. Analysts note that Qataris are provided with a wide range of social welfare benefits by the government, including free healthcare, education and subsidised housing. And suggest that because if this, Qataris nationals seem, on the whole, to be content, despite having little influence over politics, due to the generosity of the ruling elites (social welfare benefits in this small country are incredibly generous by any metric).

Saudi Arabia

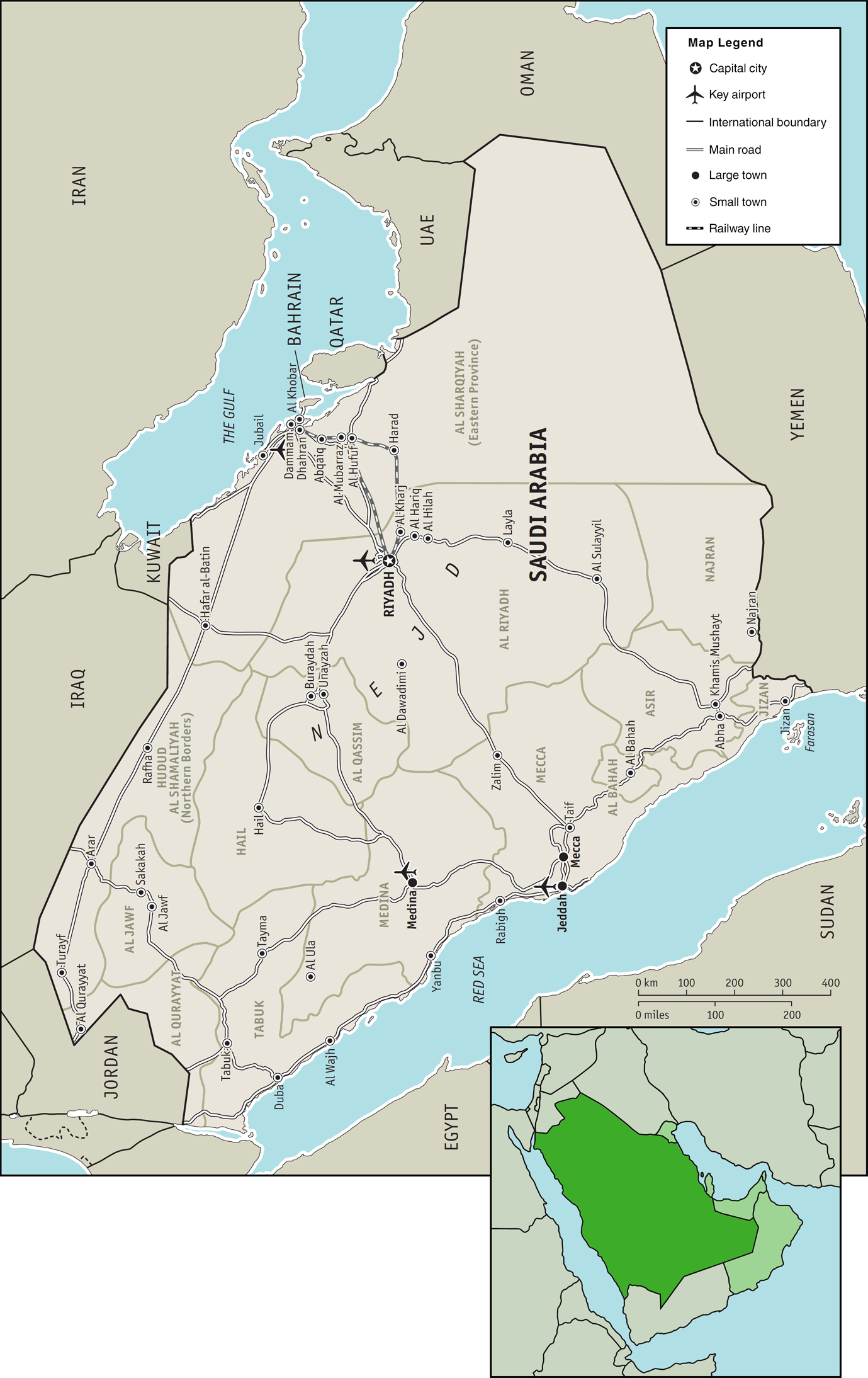

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about 830,000 sq miles (making it the largest country in the Middle East). It is bordered by the Red Sea to the west; Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait to the north; the Arabian (or Persian) Gulf, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to the east; Oman to the southeast; and Yemen to the south.

Map

With a population of almost 32.2 million (as of 2025), Saudi Arabia is the fourth most populous country in the Arab world; yet there are actually only 18.8 million Saudis amongst this number. According to the EIU (2024), Saudi Arabia is ranked 150th (out of 167 countries and territories) on its Democracy Index and is thus categorised as an “authoritarian” state by the London-based think-tank.

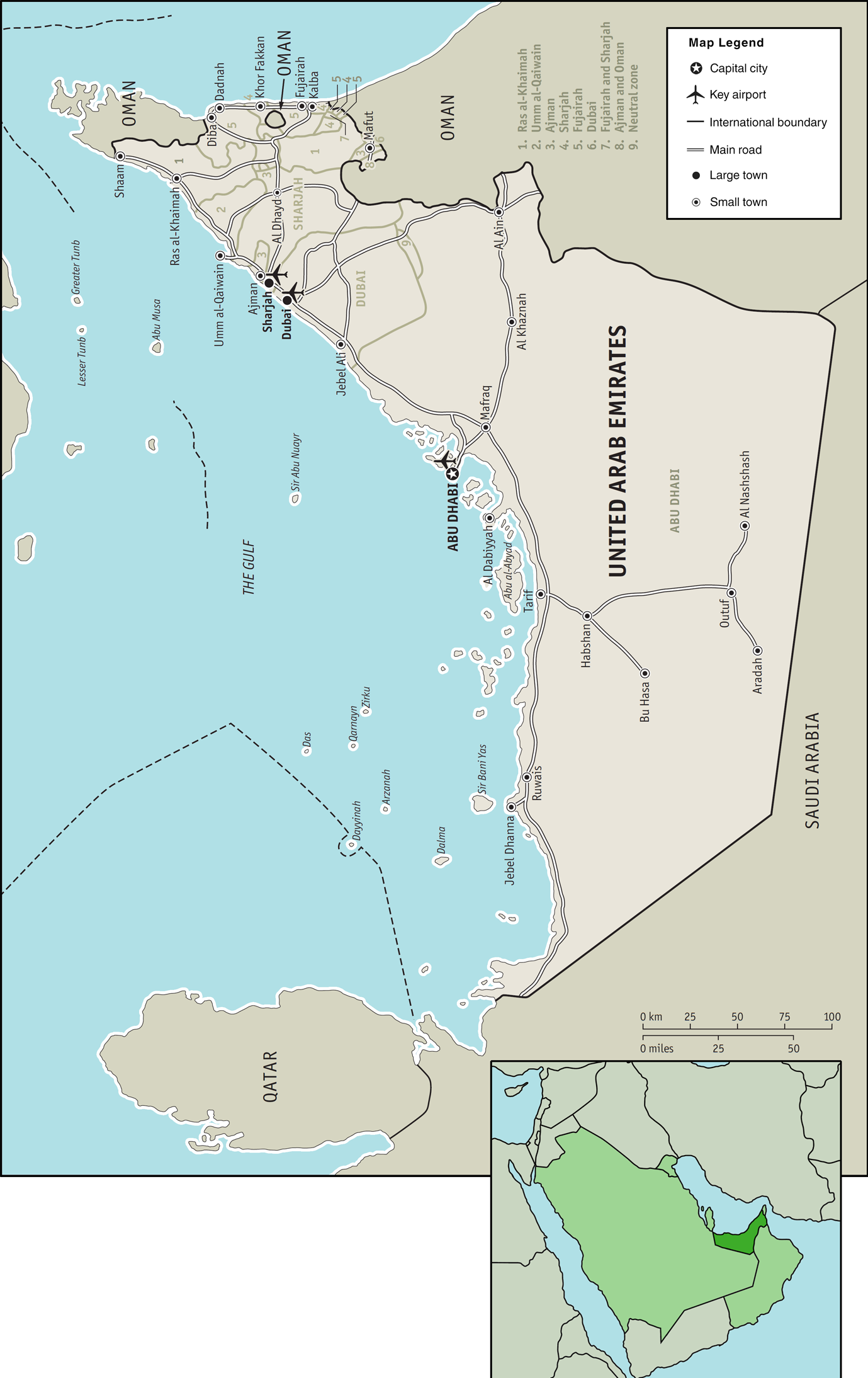

The United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates, ‘the UAE,’ or simply ‘the Emirates,’ is at the eastern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a federal elective monarchy made up of seven emirates, with Abu Dhabi serving as its capital. The seven Emirates are: Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain, Ras Al Khaimah and Fujairah. The UAE shares land borders with Oman to the east and northeast, and with Saudi Arabia to the southwest; as well as maritime borders in the Persian Gulf with Qatar and Iran, and with Oman in the Gulf of Oman.

Map

As of 2025, the UAE had an estimated population of 12.2 million, of which just one million were Emiratis. Thus, less than one in ten individuals in the UAE have claims to the country’s sovereign wealth.

According to the EIU (2024) Strong international oil prices have enabled the government of the UAE to continue to invest heavily in improving infrastructure and maintaining targeted social support, housing and employment assistance, and other benefits. In general, a high level of income per head and redistribution of funds between Abu Dhabi and less wealthy emirates in the UAE mean that there are fewer social strains or demands for democratisation than in poorer countries with comparable authoritarian political systems. In the EIU’s annual Democracy Index, the UAE was placed, “firmly in the “authoritarian” category, ranked 125th out of 167 countries and territories.

Endnotes

[1]

The “Arabian Gulf” and “Persian Gulf” refer to the same body of water located between the Arabian peninsula and Iran, but the term Persian Gulf is considered the historically recognised name. Regarding the politics of names, British readers may prefer “The Yemen” and, American readers may be more familiar with the term, “Persian Gulf” (for they’ve the “Gulf of Mexico”). Indeed, the Persian Gulf is the name some will insist upon using. No judgement is here made by the continued use of Arabian Gulf when referring to the said six countries, and to assuage any that may take umbrage, I recommend you allow your mind’s eye to read Persian Gulf each time you see Arabian Gulf (not that this will necessarily suffice as consolation, but I myself do the same, each time for instance I see in print, ‘mankind,’ I voice it in my head as, ‘humankind’). The issue with naming the Gulf is commonly covered in the outset of books that focus on the region. In The Gulf states: a modern history, David Commins writes that naming the body of water between Iran and Arabia is rooted in convention rather than nature. It does happen to be the case that Ancient Greek mariners, early Muslim cartographers and 15th century Portuguese explorers all referred to it as the Persian Gulf and, only in the 1950s, with the rise of Arab nationalism, did the term Arabian Gulf take root and gain some popular currency. My rationale is twofold, first, the word ‘Arabian’ comes most naturally to me, Arabic is the language I studied as an undergraduate in both London and Alexandria. Secondly, the native tongue in all six GCC countries, the geographic area of my academic research interest, is Arabic. In all instances, be it in Manama, Muscat, Abu Dhabi or Dubai, it was always referred to in meetings and at conferences that I attended as “al khaleej al arabi.”

The Arabian Gulf countries are often lumped together and painted as archetypal rentier states that are “resource rich [and] labour poor.” The contention that oil is a curse, for the economies that were not diversified prior to its commercial extraction, is at first pass, an immutable truism but, one that, on second pass, is only valid accept for when it is not (see, e.g., Conca, 2013; Rosser, 2006). It would be fair to say that the jury is still out but, as was argued in a 2017 paper entitled: “Oil Rent, the Rentier State/Resource Curse Narrative and the GCC Countries,” oil-rent has massively benefitted the citizenries of the Arabian Gulf in social welfare terms. A number of additional factors should also be considered in this regard, not least the ways in which imperial powers have long interfered. First of all, the oil-rich Arabian Gulf are too dissimilar from say Russia or Venezuela to be bundled together and conveniently be cast as “petrostates” — i.e., they do not satisfactorily comply with Thomas Friedman’s (2006) First Law of Petro-politics. Secondly, neither can these economies be placed in the same basket as their fellow oil-rich Middle Eastern states: Algeria (population c. 44 million), Iran (pop. 83mn) and Iraq (pop. 41mn), as the Arabian Gulf six are all absolute monarchies, not republics and have a total national population of just 25 million (when expatriate migrant workers are factored out). For a primer on Algeria, consider the section on this north African country’s civil war in Robert Fisk’s The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East (2005). Fisk, recall, is the author of Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War (1992) and was a prominent journalist covering the Iraq War who notably coined the appellation, “Lord Blair of Kut al-Amara”. For readers on Iran consider the works of Axworthy (2007), Empire of the Mind: A History of Iran and Amanat (2017), Iran: A Modern History. For what is still referred to as modern-day Mesopotamia by some (think The Epic of Gilgamesh), consider Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq by Makiya (1998) and Once Upon a Time in Iraq by Bluemel and Mansour (2020). A third point is — Iraq’s brief 1990 foray into Kuwait aside — the GCC’s abundance of oil has not caused it to suffer internal armed conflict as has occurred in some fellow OPEC countries like Angola, Nigeria and Libya. There is an argument to be made that Iraq was goaded into invading Kuwait and believed it had been issued something akin to a get-out-of-jail-free card by the Americans (Gause, 2002; Sciolino & Gordon, 1990; Stein, 1992). Fourth and finally, neither can it be said that this bloc’s abundance of oil has caused it to suffer internal armed conflict as has occurred in some fellow OPEC countries like Angola, Nigeria and Libya. The semi-autobiographical novel, In the Country of Men by Hisham Matar (2006) and Sandstorm: Libya in the Time of Revolution (2012) by Lindsey Hilsum together comprise a good introduction to Libya. It should be noted that in signs of these contemporary times, several Arabian Gulf countries entwined themselves in Libya’s discordant affairs in the years after the Arab Spring.

On another matter, in terms of the countries of the Arabian peninsula, The Yemen is the seventh. It is not part of the GCC grouping and thus is often omitted from comparative analyses of the peninsula’s sociocultural and political-economy trajectories. With regard to Yemen, the following works are highly recommended and, without favour, presented chronologically, Freya Stark’s The Southern Gates Of Arabia: A Journey In The Hadbramaut (1936), Yemen by Tim Mackintosh-Smith (2000), Steven Caton’s Yemen Chronicle: An Anthropology of War and Mediation (2005) and, Yemen: Dancing on the Heads of Snakes by Victoria Clark (2010). Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s overt military action in Yemen began in 2015. According to Ragab (2017), these countries felt obliged to reposition themselves in the region as countries capable of using not only money and diplomacy, but also military means in the perusal of their foreign policy objectives in relation to maintain their respective domestic stabilities.

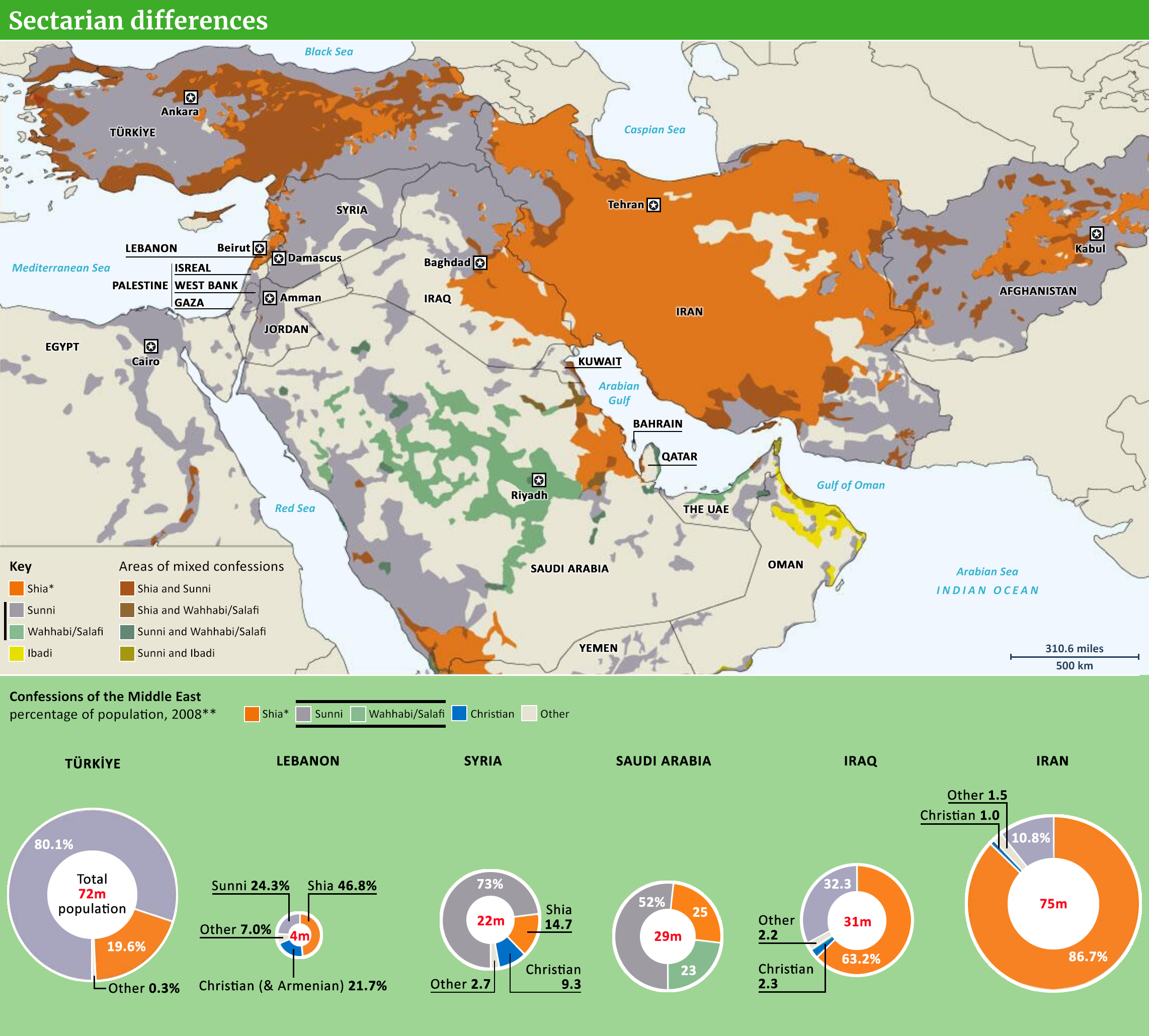

[2]

The map below gives details on the confessional divides on and around the Arabian peninsula. Although the data used to compile the map is over a decade old, no similar, more contemporary, map exists to my knowledge (the work is based on that carried out by Dr Michael Izady) and later used by The Financial Times of London. Interestingly, it draws a distinction between ‘Sunni’ Islam and the schools most popular in Saudi Arabia (Wahhabi/Salafi). To gain a deeper understanding of the region’s sectarian politics the following are worth investigating: Axworthy (2017) and Potter (2014). The work by Matthiesen (2013)—Sectarian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Spring That Wasn’t—provides a thorough analysis of the relationship between Bahrain (with its Sunni monarchy reigning over a domestic population that is majority Shia) and Saudi Arabia. It is worth too paying particular heed to the sentiments of Haddad (2014, p. 67) when it comes to the term sectarian: “until scholars are able to satisfactorily define “sectarianism,” a more coherent way of addressing the issue would be to use the term “sectarian” followed by the appropriate suffix, e.g., sectarian unity; sectarian discrimination, and so forth.”

* Includes gnostic Alawites & Alevis. ** Dated; see Table below. Expand map.

* Includes gnostic Alawites & Alevis. ** Dated; see Table below. Expand map.

Table: Religions in 2023 (%)

| Country | Sunni | Shia | Other |

| Bahrain a | 28 | 54 | 18 |

| Kuwait b | 66 | 17 | 17 |

| Oman c | 47 | 7 | 46 |

| Qatar d | 66 | 12 | 22 |

| Saudi Arabia e | 81 | 9 | 10 |

| The UAE f | 67 | 7 | 26 |

| Iran | 17 | 81 | 1 |

| Iraq | 35 | 61 | 4 |

| Jordan | 93 | 2 | 5 |

| Egypt | 90 | < 1 | 10 |

| Yemen | 44 | 55 | 1 |

As will become apparent when reading the notes to the above table, the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) relies heavily on the U.S. State Department’s annual International Religious Freedom Reports (that are submitted to the House of Congress annually in accordance with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998). Those said reports (linked to in the Table’s notes, below) paint a common theme: virtually all Gulf citizens are Muslim, but official demographics published by these countries do not delineate along confessional lines so, local media and think-tank reporting is relied upon.

a

The US state department’s 2023 IRF report on Bahrain estimates the total population to be approximately 1.5 million with Bahrainis numbering around 720,000 (June 2023 – compare with Arabian Gulf data). The Bahraini government does not publish statistics that delineate its the Shia and Sunni Muslim populations but, “estimates from NGOs and the Shia community state Shia Muslims represent a majority (55 to 70 per cent).”

b

The IRF Report on Kuwait The U.S. government estimates the total population at 3.2 million (midyear 2022). U.S. government figures also cite the Public Authority for Civil Information (PACI), a local government agency, which reports that the country’s total population was 4.8 million in 2023. As of June, PACI reported there were 1.5 million citizens and 3.3 million noncitizens. PACI estimates 74.7 percent of citizens and noncitizens are Muslims. The national census does not distinguish between Shia and Sunni Muslims. Nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and the media estimate approximately 70 percent of citizens are Sunni Muslims, while the remaining 30 percent are Shia Muslims (including Ahmadi and Ismaili Muslims, whom the government counts as Shia).

c

The IRF Report on Oman states that around 41 per cent of the Sultanate’s population constitutes foreign guest workers. Regarding the national Omani citizens, it is estimated that 45 per cent are Sunni, 45 per cent are Ibadi and most of the remainder are Shia (like its neighbours, the Omani government does not directly publish religious confession breakdowns). Note that the ARDA percentages in the Table above differ from those provided by the IRF.

d

According to the IRF Report on Qatar, as of 2023 Qataris made up approximately 11 per cent of the country’s total population and that “most citizens are Sunni, and almost all others are Shia.”

e

The IRF Report on Saudi Arabia estimates that around 85 per cent of Saudis are Sunni. The remainder are Shia, but in the oil-rich Eastern provinces of the country, this latter group comprises a substantial fraction (see: Oil’s corruptive capacity).

f

The 2023 IRF Report on the UAE suggests that approximately 11 per cent of the country’s population are Emiratis, of whom more than 85 per cent are Sunni. Most of the remainder, according to the report are are Shia citizens, “who are concentrated in the Emirates of Dubai and Sharjah.”

[3]

Country profile information is compiled from, amongst others, the following sources (on each of the six country profile pages, full reference information is provided):

Academic

Cambridge University Press →

Cambridge University Press →

Intellect Discover →

Intellect Discover →

Oxford Academic →

Oxford Academic →

Routledge →

Routledge →

Sage →

Sage →

Springer →

Springer →

Media outlets

The Economist Intelligence Unit →

The Economist Intelligence Unit →

Financial Times →

Financial Times →

Middle East Economic Digest →

Middle East Economic Digest →

Organisations

Arab Monetary Fund →

Arab Monetary Fund →

Bertelsmann Transformation Index →

Bertelsmann Transformation Index →

Energy Information Agency →

Energy Information Agency →

Energy Institute →

Energy Institute →

Eurostat →

Eurostat →

Fraser Institute →

Fraser Institute →

Freedom House →

Freedom House →

International Energy Agency →

International Energy Agency →

International Monetary Fund →

International Monetary Fund →

Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries →

Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries →

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development →

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development →

Reporters sans frontières →

Reporters sans frontières →

United Nations Development Program →

United Nations Development Program →

Varieties of Democracy →

Varieties of Democracy →

The World Bank →

The World Bank →

World Economic Forum →

World Economic Forum →

World Intellectual Property Organisation →

World Intellectual Property Organisation →

World Trade Organisation →

World Trade Organisation →

References

Abouzzohour, Y. (2021, March 8). Heavy lies the crown: The survival of Arab monarchies, 10 years after the Arab Spring. Brookings Doha. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/heavy-lies-the-crown-the-survival-of-arab-monarchies-10-years-after-the-arab-spring/

Amanat, A. (2017). Iran: A Modern History. Yale University Press.

Axworthy, M. (2007). Empire of the Mind: A History of Iran. C. Hurst & Co.

Axworthy, M. (2017, August 25). Islam’s great schism. New Statesman, 146(5381), 22–27. https://www.newstatesman.com/world/middle-east/2017/08/sunni-vs-shia-roots-islam-s-civil-war

Bloch, R. (2010). Dubai’s Long Goodbye. International journal of urban and regional research, 34(4), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01014.x

Bluemel, J., & Mansour, R. (2020). Once Upon a Time in Iraq. Penguin Random House.

Brannagan, P. M., Reiche, D., & Bedwell, L. (2023). Mass social change and identity hybridization: the case of Qatar and the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Identities, 30(6), 900–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2023.2203576

Caton, S. C. (2005). Yemen Chronicle: An Anthropology of War and Mediation. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Clark, V. (2010). Yemen: Dancing on the Heads of Snakes. Yale University Press.

Collinson, P. (2009, May 26). Dubai suffers biggest house price slump. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2009/may/26/dubai-property-crash

Colombo, S. (2012). The GCC and the Arab Spring: A Tale of Double Standards. The International Spectator, 47(4), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2012.733199

Commins, D. (2012). The Gulf states: a modern history. I. B. Tauris.

Conca, K. (2013). Complex Landscapes and Oil Curse Research. Global Environmental Politics, 13(3), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_r_00187

Crisp, J., & Corfe, O. (2023, December 9). Inside the luxurious lives of the Russians of Dubai. The Daily Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2023/12/09/inside-the-luxurious-lives-of-the-russians-of-dubai/

Cull, N. J. (2022). The Greatest Show on Earth? Considering Expo 2020, Dubai. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 18(2), 49–51. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-022-00267-1

Davidson, C. (2009). Dubai: foreclosure of a dream. Middle East report, 251(Summer), 8–13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27735295

EIU. (2021). Are Saudi Arabia’s plans to become the main business hub for the Middle East achievable or a step too far? The Economist Intelligence Unit. https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=may21saudiwp

EIU. (2025). Democracy Index 2024: What’s wrong with representative democracy? Economist Intelligence Unit.

Fisk, R. (1992). Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War (2 ed.). Oxford University Press.

Fisk, R. (2005). The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. Fourth Estate/HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

Friedman, T. (2006). The First Law of Petropolitics. Foreign Policy, 154(May), 28–36. https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/16/the-first-law-of-petropolitics/

Gause, G. (2002). Iraq’s decisions to go to war, 1980 and 1990. The Middle East Journal, 56(1), 47–70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4329720

Haddad, F. (2014). Sectarian relations and Sunni identity on post-civil war Iraq. In L. G. Potter (Ed.), Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf (pp. 67–115). Oxford University Press.

Hilsum, L. (2012). Sandstorm: Libya in the Time of Revolution. Faber & Faber.

IMF. (2024). Saudi Arabia Country Report (Vol. 24/280). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2024/09/03/Saudi-Arabia-2024-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Informational-Annex-554530

IMF. (2024). World Economic Outlook [Dataset]. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April

Kamrava, M. (2012). The Arab Spring and the Saudi-Led Counterrevolution. Orbis, 56(1), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2011.10.011

Kamrava, M. (2013). The Modern Middle East: A Political History since the First World War (3 ed.). University of California Press.

Maccioni, F. (2024, July 8). Dubai property market stays strong as demand from ultra-rich continues. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/dubai-property-market-luxury-homes-b2575845.html

Mackintosh-Smith, T. (2000). Yemen. Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Makiya, K. (1998). Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq (2 ed.). University of California Press.

Matthiesen, T. (2013). Sectarian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Spring That Wasn’t. Stanford University Press.

Matar, H. (2006). In the Country of Men. Viking Press.

Morganbesser, L. (2025, February 23). Allies at Odds: Tracking the Rivalry between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Center for International Affairs, Harvard University. https://epicenter.wcfia.harvard.edu/blog/allies-odds-tracking-rivalry-between-saudi-arabia-and-united-arab-emirates

Pelham, N. (2022, July 28). MBS: Despot in the desert. The Economist, 444(9307). https://www.economist.com/1843/2022/07/28/mbs-despot-in-the-desert

Potter, L. G. (Ed.) (2014). Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf. Oxford University Press.

Ragab, E. (2017). Beyond Money and Diplomacy: Regional Policies of Saudi Arabia and UAE after the Arab Spring. The International Spectator, 52(2), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2017.1309101

Renaud, B. (2012). Real Estate Bubble and Financial Crisis in Dubai: Dynamics and Policy Responses. Journal of real estate literature, 20(1), 51–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2012.12090313

Rosser, A. (2006). The political economy of the resource curse: A literature survey. Institute of Development Studies Working Paper Series. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12413/4061

Rutledge, E. J. (2023). The tour guide role in the United Arab Emirates: Emiratisation, satisfaction and retention. Tourism and hospitality research, 23(4), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221122488

Rutledge, E. J. (2024). The tour guide profession: An attractive option for UAE nationals majoring in tourism? Tourism and hospitality research, 0(online first), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584241278451

Samuel-Azran, T., & Manor, I. (2023). Empirical support for the Al-Jazeera Effect notion: Al-Jazeera’s Twitter following. The international communication gazette, 85(5), 386–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/17480485221142466

Schwarz, J. (2016, January 6). One Map That Explains the Dangerous Saudi-Iranian Conflict. The Intercept_. https://theintercept.com/2016/01/06/one-map-that-explains-the-dangerous-saudi-iranian-conflict/

Sciolino, E., & Gordon, M. R. (1990, September 23). U.S. Gave Iraq Little Reason Not to Mount Kuwait Assault, Article. The New York times.

https://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/23/world/confrontation-in-the-gulf-us-gave-iraq-little-reason-not-to-mount-kuwait-assault.html

Stark, F. (1936). The Southern Gates Of Arabia: A Journey In The Hadbramaut. J. Murray.

Stein, J. G. (1992). Deterrence and Compellence in the Gulf, 1990-91: A Failed or Impossible Task? International Security, 17(2), 147–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539171

The Economist. (2018, September 27). Sweet deserts. The Economist, 428(9111), 58. https://www.economist.com/international/2018/09/27/how-the-united-arab-emirates-became-an-oasis-for-tax-evaders

The Economist. (2024, July 6). Call of the desert. The Economist, 452(9404), 71–72. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/culture/2024/07/04/can-saudi-arabia-become-a-premier-tourist-hotspot

Troianovski, A. (2023, March 15). ‘Russia Outside Russia’: For Elite, Dubai Becomes a Wartime Harbor. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/13/world/europe/russia-dubai-ukraine-war.html

Wood, G. (2022, March 3). Absolute Power. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/04/mohammed-bin-salman-saudi-arabia-palace-interview/622822/

Worth, R. F. (2020, January 9). The M.B.Z. Moment. New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/09/magazine/united-arab-emirates-mohammed-bin-zayed.html

Worth, R. F. (2021, January 28). The Dark Reality Behind Saudi Arabia’s Utopian Dreams: Screenland. New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/28/magazine/saudi-arabia-neom-the-line.html

Zraick, K. (2016, January 12). The Persian (or Arabian) Gulf is Caught in the Middle of Regional Rivalries. The New York times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/13/world/middleeast/persian-gulf-arabian-gulf-iran-saudi-arabia.html

Elsevier

Elsevier